High inflation will impact your tax bill

2022 tax brackets will be adjusted for inflation

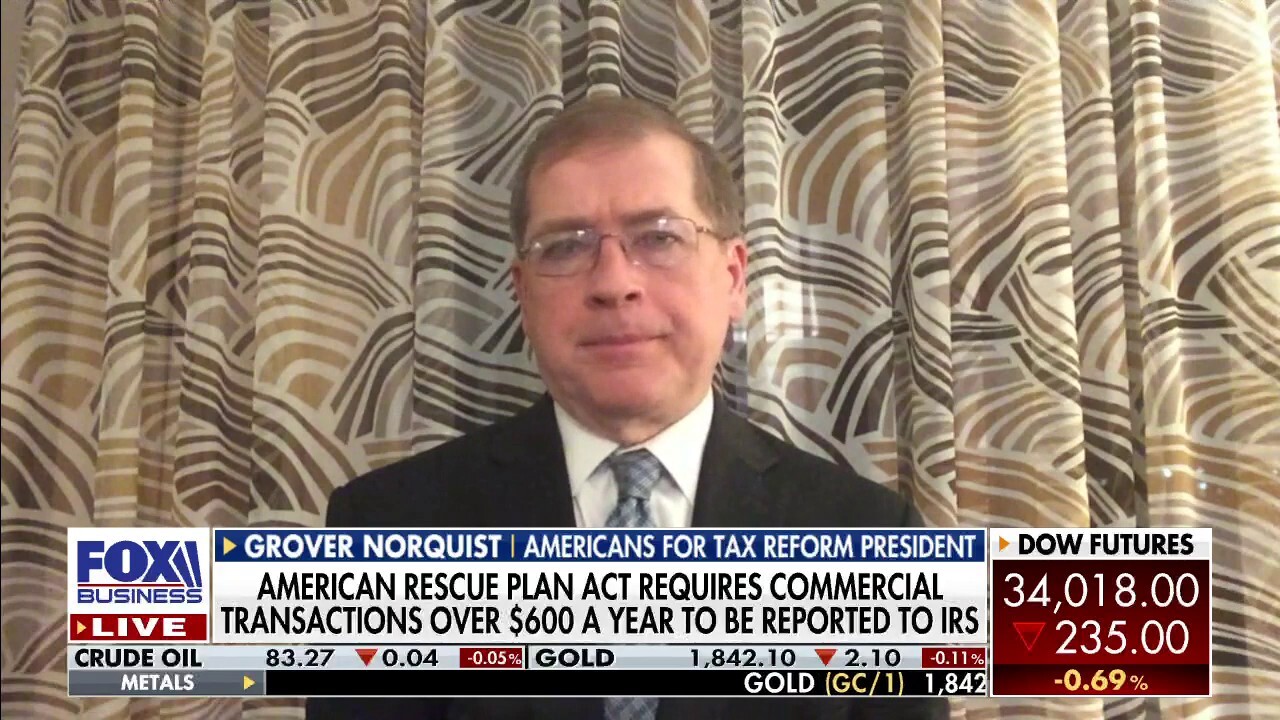

Biden's IRS reporting device for third-party payment processors 'will affect your taxes,' says Norquist

Americans for Tax Reform President Grover Norquist argues people who have a side hustle and independent contractors are 'being swept up' by the administration's latest IRS push.

Wordle. Sourdough starters. Tiger King. New terms we’ve come to know as normal during the COVID-19 pandemic. But the pandemic has also brought back an old term: high inflation.

Consumer prices rose 7% in 2021— the highest annual rate of inflation since 1982. A single factor alone cannot explain the phenomenon: some is attributable to the federal government's aggressive COVID-19 response, injecting unprecedented amounts of money into the economy, but sudden shifts in consumer spending and supply-chain bottlenecks helped raise prices too. No matter the cause, inflation matters a lot come tax season.

FED MAY HIKE RATES 7 TIMES THIS YEAR: BOFA

Back in the late 1970s, when inflation regularly hovered around or above 7%, tax brackets were not adjusted, or indexed, to inflation. Then, as people's wages rose on paper, they were pushed into higher tax brackets, even though inflation meant their real income and purchasing power had not changed. This is called bracket creep, and it amounts to a stealth tax increase. In response to the problem, the Economic Recovery Tax Act of 1981 began indexing tax brackets and other parts of the tax code to inflation.

THREE TAX CHANGES TO KNOW BEFORE FILING

Today, tax brackets, the standard deduction, 401(k) contribution limits, and programs for low-income workers like the Earned Income Tax Credit get adjusted for inflation. The adjustments, however, are not perfect. To set the tax brackets for 2022, the IRS used inflation from September 2020 through August 2021, resulting in a 3% adjustment, even though inflation from 2021 to 2022 was closer to 7%.

In simpler terms, today’s unexpectedly high level of inflation will bring a slight tax increase for 2022, in spite of the adjustments. It could be evened out to some extent next year; if inflation comes down, the brackets for the 2023 tax year will include adjustments for higher inflation in the last months of 2021 due to the adjustment lag at the IRS.

GET FOX BUSINESS ON THE GO BY CLICKING HERE

Nonetheless, several parts of the individual income tax are not adjusted for inflation. Most have to do with investments: for example, the tax code's limit of $3,000 in deductions for capital losses has not been adjusted upward since 1977. Similarly, the capital gains exclusion for the sale of a primary residence, $250,000 for singles, $500,000 if filing jointly, hasn't been increased since it was created in 1997.

Capital gains tax liability is another area of the code not protected from inflation. A capital gains tax is levied on the difference between the value of an asset, such as a stock, when it is sold and the amount for which it was purchased, also known as the basis. The basis is not adjusted for inflation—so in some cases, an asset like a stock could look better on paper, but the value of the investment has stayed flat or even declined in terms of what it can buy thanks to inflation.

Inflationary gains do not represent a real increase in wealth, thus taxes on inflationary gains are taxes on "fictitious" income, which can discourage saving and investment. Changing the capital gains system to be indexed for inflation could end up being as much of a big headache, so while the existing law's lower rates on long-term gains do not fix the inflation issue, they may be the best policymakers can do within our current tax system.

Even though adjusting capital gains for inflation might be the ideal policy in an abstract sense, changing to that system could end up being as much of a headache. So, while not the ideal approach, the existing lower tax rates for capital gains may be the best policymakers can do to avoid disincentivizing savings.

It's not clear how long COVID-19-era inflation will continue. Part of the equation is how much longer the virus and its disruptions to normal economic activity stick around, but another round of stimulus spending, like the Build Back Better package, would also help keep inflation going. In either case, we are fortunate the individual income tax already adjusts for inflation, but policymakers could make the code even more resilient and responsive to fluctuating economic conditions.

Alex Muresianu is a federal policy analyst at the Tax Foundation, a nonpartisan think tank in Washington, D.C.