Investors retreat from commercial real estate bonds

Office vacancies, rising rates have investors demanding greater yields for commercial-mortgage debt.

Stock market's next big obstacle could be commercial real estate 'failures': Jason Katz

UBS managing director Jason Katz warns investors to beware of a commercial real estate collapse as banking worries persist on 'Varney & Co.'

Prices of bonds backed by commercial mortgages have recently dropped to levels not seen since the early days of the pandemic, pointing to a growing economic threat stemming from office vacancies and rising interest rates.

A small corner of the U.S. bond market, so-called commercial-mortgage-backed securities, or CMBS, have taken a beating for over a year owing to fears that owners of business parks, high-rises and other office properties could default on loans extended at a time of different work habits and lower financing costs.

That stress only deepened recently after Silicon Valley Bank’s collapse, which raised concerns that regional banks might scale back their risk-taking and become more reluctant to make commercial real-estate loans—making it harder for property owners to refinance existing debt.

Employees walk in front of a sign outside of the shuttered Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) headquarters in Santa Clara, California. (Justin Sullivan/Getty Images / Getty Images)

As of Tuesday, the average extra yield, or spread, above U.S. Treasurys that investors were demanding to hold CMBS with a triple-B rating—the lowest broad investment-grade tier—was 9.46 percentage points, according to an ICE BofA index. That was up from 7.6 percentage points at the end of February and approaching the 10.8 percentage point level reached in March 2020, when local authorities were issuing stay-at-home orders. The average price of the bonds has dropped to around 75 cents on the dollar from roughly 89 cents a year ago.

BANKS COULD BEGIN CANCELING LINES OF BUSINESS CREDIT SOON

Investors and analysts care about CMBS prices in large part because of what they signal about a much larger universe of commercial real-estate loans that aren’t sliced into securities. At the end of last year, only about 9% of the $5.4 trillion in outstanding commercial real-estate loans were bundled into private-label CMBS, according to an analysis of Federal Reserve data by BofA Global Research.

Banks are by far the largest lenders in the sector, holding 46% of all commercial real estate debt. Banks, though, typically don’t have to cut the value of the mortgages they hold on their books until borrowers have trouble making their debt payments. The CMBS market, therefore, can signal what the true value of those assets might be, a suddenly burning question for investors.

While SVB’s depositors were spooked by the bank’s losses on interest-rate sensitive bonds, some analysts worry that commercial real-estate loans could be an even bigger problem for regional banks, which are responsible for nearly 30% of commercial real-estate lending. Economists in turn have warned that challenges at regional banks are likely to reduce overall lending and drag on economic growth.

"At a bank, you don’t really know what’s going on with the commercial real estate," said Alan Todd, head of U.S. CMBS strategy at BofA Global Research. CMBS, he added, is providing "a more real-time reflection of the credit risk embedded in some of these loans."

It isn’t a perfect gauge.

General fear, along with economic fundamentals, can sometimes drive prices in the market, investors and analysts said. That could be especially true now since investors tend to use newly issued CMBS as a guide to pricing securities in the secondary market, and that issuance has largely dried up in recent months.

JOBLESS CLAIMS COME IN HIGHER THAN EXPECTED AHEAD OF MARCH JOBS REPORT

Widening CMBS spreads provided useful early-warning signals about rising commercial mortgage delinquencies in the late 2000s and mid-2010s. At the same time, a near breakdown of the market in 2008 and 2009 created a situation in which spreads suggested future losses that in many cases far exceeded what lenders ultimately faced.

As matters stand, most commercial property owners remain current on their loans. The delinquency rate among loans underlying commercial mortgage securities—including loans not only to offices but also to hotels, retail properties and industrial complexes—was 3.09% last month, according to the data firm Trepp Inc., less than half the rate from two years earlier.

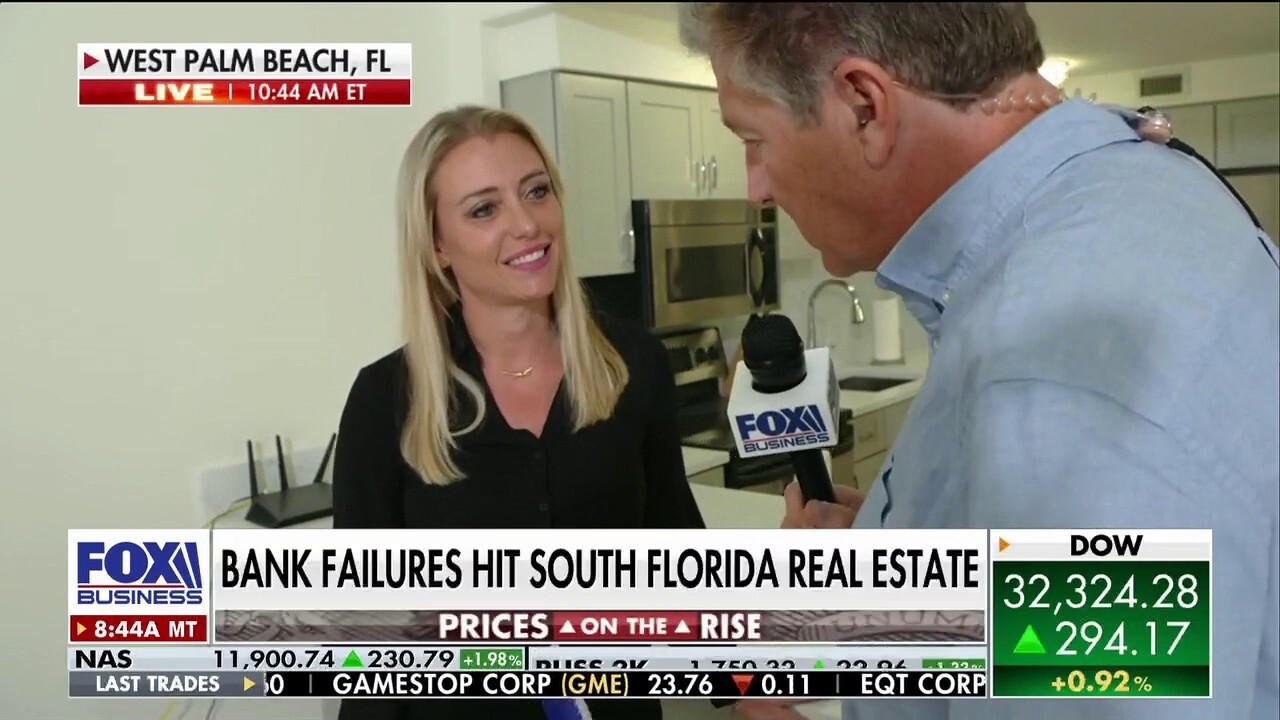

Bank failure fears spreading to Florida's real estate market

FOX Business' Ashley Webster reports from a for-sale townhome in West Palm Beach, Florida, where the local market is feeling some of the Silicon Valley Bank collapse impact.

Still, delinquencies have been rising fairly steadily since the middle of last year in the category that most concerns investors: offices. And there is wide agreement on Wall Street that delinquencies and defaults should continue to climb going forward.

That is in large part due to soaring office vacancies in many cities. In downtown areas, the office vacancy rate reached 17.6% in the last three months of 2022, up from 13.8% two years earlier, according to the real-estate services firm CBRE. Despite talk among some policy makers about turning offices into apartments, many investors say that offices would be harder to convert than some other types of properties such as malls.

MAJORITY OF WORKERS REGRET QUITTING DURING 'GREAT RESIGNATION'

High interest rates have also raised the risk of defaults. Owners with floating-rate mortgages are already making larger debt-service payments, cutting into their cash flows. Some owners with fixed-rate mortgages might have a hard time refinancing their loans at higher rates when they come due in the coming years.

It will likely take time for investors to realize losses. When commercial real estate owners can’t issue new loans to pay down their maturing debt, they sometimes hand the property to lenders, who are then forced to sell it for less than the balance of their loan. More often, though, owners are able to extend loans in the hope that time, and possibly some new investment, can improve their properties’ value.

In recent days, there have been some signs that CMBS prices might be stabilizing. Still, investors continue to approach the market with extreme caution.

CLICK HERE TO GET FOX BUSINESS ON THE GO

"The bottom line is, most people still like going to the office" at least a couple of times a week, said John Kerschner, head of U.S. securitized products at Janus Henderson Investors. In 10 years, he said, offices will continue to exist in abundance, much as malls still exist, despite widespread fears of their demise.

Still, his rough guess is that about 10% to 20% of office buildings will need to be turned over to lenders in the coming years. Prices of commercial mortgage securities with office exposure, in his view, generally still have room to fall farther.

"What we’re doing is being patient, staying away from all but the obvious trades and then just waiting for the distress to come to us, because it will happen," he said.