Global minimum tax deal hits new roadblock after Hungary opposes deal

Hungary vetoes global minimum tax deal, imperiling its passage

These tax cuts could ease inflation

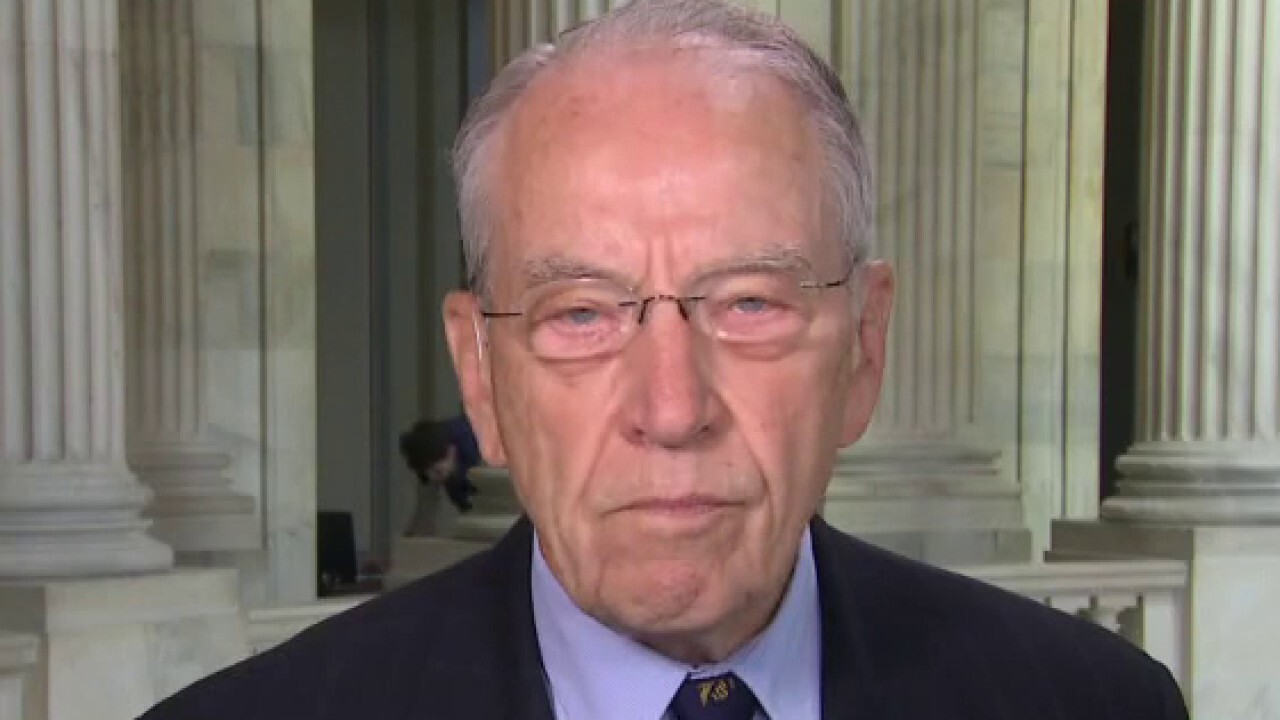

Iowa Republican Sen. Chuck Grassley gives his take on tax cuts that could provide ease to Americans as the country faces record-high inflation on 'Kudlow.'

A landmark global deal to impose a minimum tax rate on corporate profits ran into a major roadblock last week after Hungary vetoed a European Union plan to implement the measure at the end of 2023.

More than 130 countries reached a long-awaited agreement last year for a 15% global minimum corporate tax and other policies aimed at cracking down on international tax avoidance. Negotiations, which lasted for years and often seemed on the brink of collapse, were bolstered by the support of President Biden and Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen.

THESE COUNTRIES HAVE THE HIGHEST AND LOWEST CORPORATE TAX RATES

But efforts to formally install the minimum tax have since stalled out in both the U.S. – Congress has moved slowly to approve any proposal – and the EU.

Hungary vetoed the measure last week during a meeting of European Union finance ministers in Luxembourg, potentially imperiling the deal because a unanimous decision is required among the 27-member voting bloc in order for it to adopt the initiative.

The flags of the European Union member states outside the Louise Weiss building, the principle seat of the European Parliament, in Strasbourg, France, on Tuesday, Jan. 18, 2022. (Photographer: Valeria Mongelli/Bloomberg via Getty Images / Getty Images)

"Under such circumstances, implementing the global minimum tax would cause serious damage to the European economy," Hungary’s finance minister Mihály Varga said.

The deal to impose a 15% minimum tax on the profits of large corporations was agreed upon by 137 countries in 2021, paving the way for the most significant overhaul of international tax rules in a century. Governments had hoped to implement the changes next year, but mounting opposition in Europe and the U.S. means that target now seems out of reach.

"As soon as one problem gets sorted out, another one comes along," French Finance Minister Bruno Le Maire – whose country currently holds the EU's rotating presidency – said after the meeting. "We will get there in the end."

It is unclear what happens next; experts doubt that this marks the end of the global minimum tax deal. Poland previously opposed the plan, but dropped its opposition during a visit from Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen to Warsaw in May. The EU also worked with Poland to address some of its concerns, including seeking a reassurance that the 27-member bloc would link the minimum tax to a separate proposal imposing a levy on the world's 100 biggest companies.

"Obviously, this is not the end of the story, as we have seen objections emerge and then be removed before," Manal Corwin, a tax analyst at KPMG said. "In addition, it appears that there may be other countries that are willing to be first movers on implementation."

Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen speaks during a virtual roundtable with participants from Black Chambers of Commerce across the country to discuss the American Rescue Plan, Friday, Feb. 5, 2021, from the South Court Auditorium on the White House comp ((AP Photo/Jacquelyn Martin) / AP Newsroom)

Corporations employ a litany of tactics to reduce their tax liability, often by shifting profits, and revenues, to low-tax countries such as Bermuda, the Cayman Islands or Ireland, regardless of where the sale was made. The practice by American and foreign multinationals costs the U.S. tens of billions of dollars each year, according to the Treasury Department.

By getting all countries to agree to a minimum corporate tax rate, the Biden administration is seeking to eradicate certain tax havens without hurting the competitiveness of American firms. Yellen has repeatedly said that a global tax, which would apply to companies' overseas profits, would eliminate what she's described as a "global race to the bottom" in terms of corporate taxes.

The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development has pushed for years to eliminate corporate strategies that "that exploit gaps and mismatches in tax rules to avoid paying tax." The global minimum tax would apply to companies' foreign earnings, meaning that countries could still establish their own corporate tax rate at home.

The Washington-based organization previously estimated the agreement, which was signed by 137 countries and jurisdictions, will reallocate $125 billion of profits from around 100 of the world's largest and most profitable multinational corporations to countries worldwide thus "ensuring that these firms pay a fair share of tax wherever they operate and generate profits."

GET FOX BUSINESS ON THE GO BY CLICKING HERE

Lobbyist groups in the U.S. have also argued that a global minimum tax rate could hurt U.S. competitiveness by driving business out of the country.