Bank bureaucracies continue to taint coronavirus small business relief options, leave many on the curb

Government officials say banks need to work harder to implement the loan program

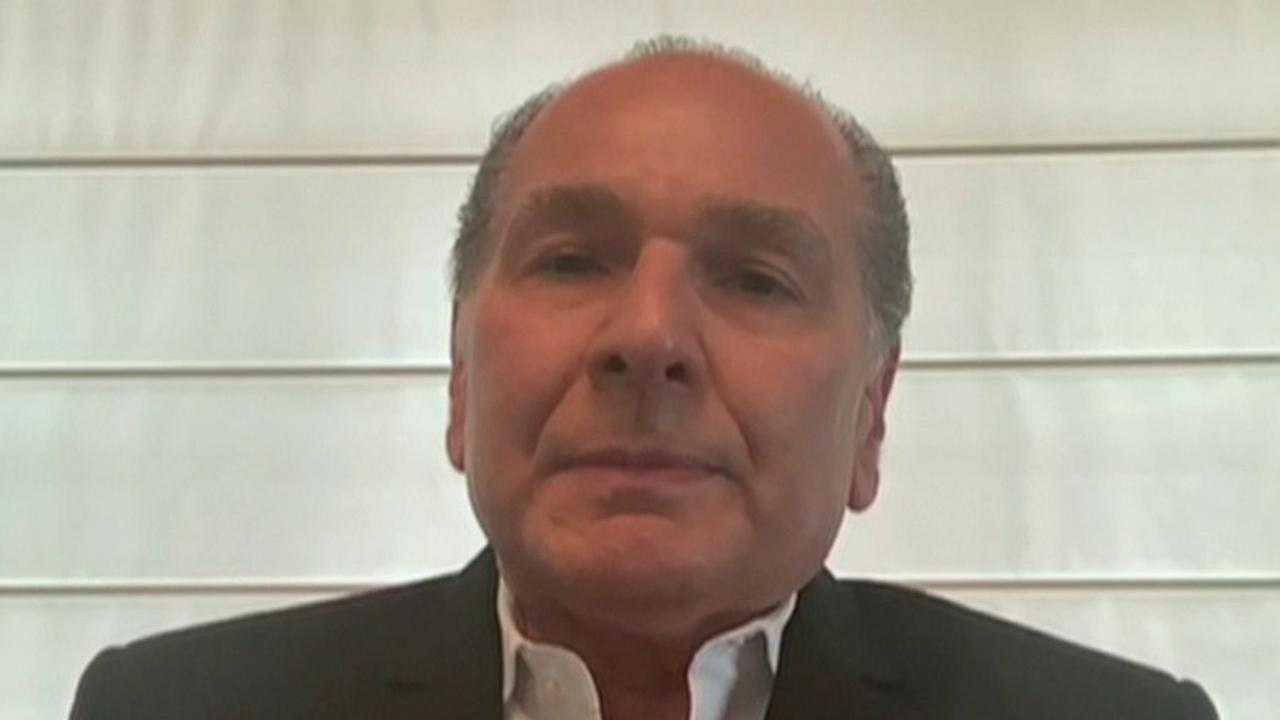

Joseph Shamie should be high on the government's list of small-business people eligible to receive much-needed stimulus money as part of its coronavirus pandemic relief program: His company, Delta Children, is the largest U.S. manufacturer of children's furniture, employing 300 people in the country and raking in about $300 million a year in revenues, before the outbreak of the virus.

He’s trying not to lay off a single employee but just needs a bridge loan to get through the next several weeks until his factories are fully up and running and people are once again out shopping and buying his products.

IVANKA TRUMP HIGHLIGHTS $1.6B CORONAVIRUS SMALL BUSINESS ASSISTANCE FROM PRIVATE SECTOR

But so far Shamie can’t get a dime out of the program. Last week, his bank, Wells Fargo, turned him down saying it can’t make loans because of past regulatory settlements. Other banks won't even process his application because he isn't a regular customer.

"I'm trying to not lay off anyone, but I’m dipping into my reserves now in order to keep people," Shamie told FOX Business in a telephone interview. "But all the banks are telling me 'sorry, Joe, we can't help you,' and like everyone else I need the money."

Unfortunately, Shamie's experience isn't an outlier; FOX Business has interviewed nearly a dozen small business owners about the government's virus-related small business loan program – intended to give these companies access to cheap capital until the worst of the pandemic is over and the economy can recover. Their stories are strikingly similar: An inability to get access to the money because they don't have a client relationship with a bank or they have one that doesn't meet the bank's strict criteria. Bank bureaucracies that offer little, if any, explanation for not handling their applications often blame agencies of the federal government, such as the Treasury Department or the Small Business Administration for rejected applications. The banks say some agencies have failed to provide proper guidelines to make loans or in the case of the SBA, they don’t have systems in place for handling the rush for money from thousands of cash-strapped small businesses.

Government officials, meanwhile, say banks need to work harder to implement the loan program.

The result is not just confusion and anxiety among small businesses, but the larger economic problem that so many firms won't have access to money in a timely fashion they will have to lay off or furlough employees. The severe economic recession precipitated by the pandemic may soon spiral into a depression that will be hard to reverse.

And it's not as if the money isn't there; under the pandemic stimulus plan, $350 billion was earmarked to provide government-backed, low-interest loans to small businesses, as defined by companies with fewer than 500 employees. The businesses would receive the lesser of $10 million or a percentage of their payroll. The loans would be forgiven if the business didn't lay off its workforce. The SBA has a separate, $10 billion grant program to small businesses.

The efforts were set to begin last Friday, and as FOX Business first reported, the administration and Congress increased the loan program by tens of billions of dollars, bringing the total to $500 billion that could be spread out to the nation’s small businesses.

Demand for the loans came swiftly; many small businesses had been working with their banks and accountants for more than a week before the program's official start date, as details of the entire $2.2 trillion stimulus package began to emerge. The initial indications seemed promising as bank reps consulted with their customers about the process.

WELLS FARGO ASSET CAP EASED FOR CORONAVIRUS SMALL BUSINESS LOANS

But around Wednesday and Thursday of last week, just before the plan's intended launch, banks began to alert clients that neither the Treasury Department nor the SBA – which would administer another chunk of grant money – had given them guidelines to start doling out the cash by its start date.

Those guidelines eventually came, albeit at the 11th hour, when Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin announced last Thursday that the federal government now had finalized its plan to begin its small-business relief effort, and that banks should be ready to start writing checks. By Friday afternoon, several thousand loan applications were processed, or about $2 billion in loans, the Wall Street Journal reported, but that well understated the size and scope of demand. Bank of America was among the first banks to begin the loan program Friday morning. By the end of business Friday, a spokesman said it had processed $7 billion worth of loans from 75,000 applications.

To small business owners, like Shamie, the money seemed like a godsend. Restaurants, salons and midsize factories have slashed payrolls as a result of the government-mandated social-distancing order that will remain in effect at least until the end of April.

These businesses employ nearly 50 percent of the American workforce, and just as they have suffered during the pandemic, so has the nation's economy. Last Thursday, 6.6 million people filed for initial unemployment claims – the most ever to file for claims in a week, while other studies have shown that unemployment could reach levels not seen since the Great Depression, unless small businesses got the money they needed and held on to their workers.

SMALL-BUSINESS CONFIDENCE IN US ECONOMY DROPPED IN MARCH: NFIB

And that was Shamie's plan. Delta Children operates a factory in Wisconsin and distribution centers in California and New Jersey. The family-run company (Shamie is co-president with his brother) is headquartered in Manhattan.

“I’ve held on to my employees through other crises, and I wasn't going to stop now," he said.

But when it came time to begin the loan application process, Shamie's bank, Wells Fargo, began to balk. Shamie told FOX Business he spent days dealing with the bank on various issues. “We submitted a series of applications and the rules kept changing,” he said.

Eventually, Wells told him he should go elsewhere. The stated reason by a Wells Fargo branch executive: Wells was the subject of a massive government settlement involving the creation of fake checking and savings accounts on behalf of its customers.

The scandal was a huge black eye for one of the nation's premier commercial banks, costing its CEO, John Stumpf, his job and forcing the company to pay billions of dollars in fines and restitution.

GET FOX BUSINESS ON THE GO BY CLICKING HERE

As it was explained to Shamie by the Wells official he was dealing with, the costs associated with the scandal is making it impossible for the bank to hand out loans, even those guaranteed by the federal government. He would have to look elsewhere for the money.

"We've been with Wells for 20 years, and the bank has been a great supporter of our business," Shamie said. "But our contact there told us because of that settlement they can't lend to us. They apologized, gave us contacts at other banks, and that was it."

A spokesman for Wells didn't return numerous emails and telephone calls to comment on Shamie's situation. He did alert FOX Business to a company memo that stated Wells Fargo would now expand its loan program after the Federal Reserve announced Wednesday that it would lighten its account-scandal restrictions on the bank specifically for virus-relief loans. A Treasury spokesman had no comment.

A representative of the Federal Reserve, which provides front-line regulatory oversight of banks like Wells, told FOX Business that the cost of the account-fraud scandal totaling close to $3 billion could have impacted Wells’ capital requirements, and reduced its ability to make any loans, including those part of the virus relief package. He declined further comment.

Of course, no one expected a multibillion-dollar loan program in the middle of a global pandemic to run seamlessly. But such bottlenecks also appear to be the result of poor planning on basic matters; the federal government could have immediately waived capital requirements at Wells and all banks to make special loans in a time of national disaster, banking experts tell FOX Business.

CLICK HERE TO READ MORE ON FOX BUSINESS

Meanwhile, Shamie took his bank's advice and began calling others, such as JPMorgan Chase and HSBC. But then he ran into another problem: Because of the huge loan demand, the big banks were prioritizing customers, even their existing ones. At Bank of America, small business clients needed both a banking relationship and to have a credit card or some other business dealing to get their loan applications processed.

New customers, like Shamie, were turned away.

"JPMorgan didn’t even want to look at my application," he said.

Some banks, like Citigroup, didn't have their system set up to handle loans, even for their own customers. As of Wednesday, Citigroup still isn't processing loans. A spokeswoman declined to comment.

Shamie, meanwhile, is looking at what he can do next. He’s heartened by Wells' recent announcement that it will soon start to more fully participate in the loan program, though he has yet to hear back on his application. He needs money, and needs it fast or he will be forced to further dip into his reserves and possibly lay off workers just to keep the lights on at his factory and distribution outlets.

"I don't want to do layoffs, and we will do our best, but I can't make any promises," he said.