Mnuchin suggests private equity firms can keep controversial tax loophole

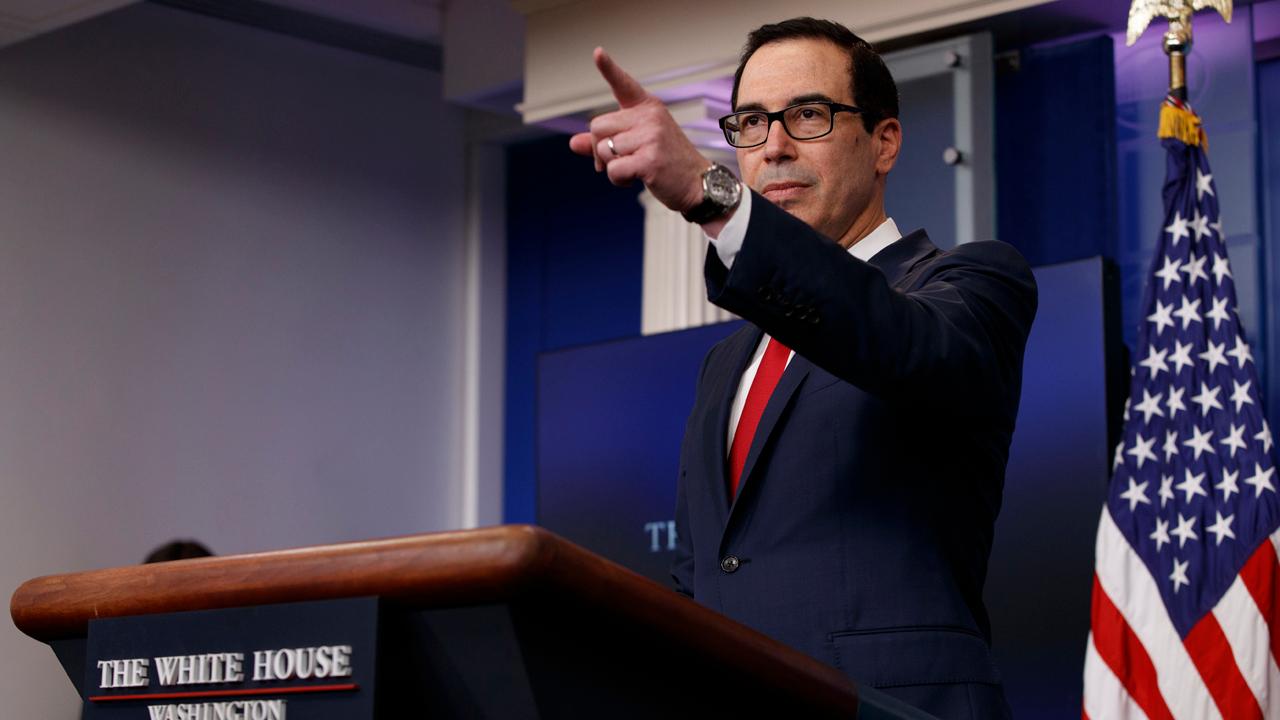

Private equity firms were high-fiving Tuesday afternoon when Treasury Secretary Steven Mnunchin suggested that the industry would be able to fully retain a lucrative but controversial tax loophole, under a budget and tax proposal being considered by the Trump administration, FOX Business has learned.

Speaking at the Delivering Alpha conference in New York, Mnuchin said the so-called “carried interest deduction” would end under President Donald Trump’s tax plan, but only for hedge funds, not private equity firms. Hedge funds rarely, if ever, use the deduction, but for the private equity business, the carried interest loophole saves the industry billions of dollars each year.

“The president has made it very clear that for hedge funds, they will not have the benefit of carried interest,” Mnuchin said during the conference. “We want to make sure that we encourage jobs, so that is something we’re still working on.”

Mnuchin didn't address private equity use of the carried interest loophole during his remarks and a Treasury spokesman wouldn't deny that the end of the deduction will only apply to hedge funds.

For years, public policy groups and mostly Democratic lawmakers have targeted eliminating the carried interest deduction as a form of welfare for the rich, since private equity companies and their investors so heavily benefit from the loophole. But by omitting private equity firms from his comments, Mnuchin was sending a strong signal to the $2.5 trillion industry that it will retain its most cherished loophole that saves firms around $2 billion a year.

It also relieves the Trump administration from a costly battle with a large class of GOP donors—the private equity and hedge fund business. Unlike private equity firms, hedge funds rarely utilize the carried interest deduction, so most hedge fund investors would not be alarmed by the move, tax experts say. Carried interest is also used by the real estate industry, where the president earned some of his massive net worth, and that industry would likely still benefit from the loophole, tax experts say.

Meanwhile, one of President Trump’s outside economic advisers is Stephen Schwarzman, the chief executive officer of private equity powerhouse Blackstone Group, which benefits substantially from the tax break. A spokeswoman for the Blackstone Group didn’t return calls for comment.

“We’ve seen no indication that [Trump’s] going to eliminate the carried interest rate for private equity funds,” said James Maloney, vice president of Public Affairs at the American Investment Council, the private equity industry’s main lobby group. “We have been in touch with the administration about the benefits of full interest deductibility. [Mnuchin] has indicated that it's his preference to maintain full interest deductibility.”

During the 2016 presidential campaign, then-candidate Trump said he would end the deduction for everybody during his populist push to win the White House. But the private equity industry—led by behemoths like the Blackstone Group, Carlyle Group and KKR—have been successfully fighting for the loopholes for years, and at least for now, they appear to have convinced the Trump administration not to touch its sacred cow.

Hank Sheinkopf, a Democratic political consultant called the Trump plan on carried interest “a bait-and-switch,” since the president promised to end it completely, but is now eliminating the deduction for investors who rarely use it while giving the powerful private equity lobby a gift.

“Hedge funds are an easy populist target,” Sheinkopf said. “He has to do something to meet the populist promise on taxes. The way to do that is to go after a group that’s disliked and for who they believe take advantage of the carried interest rate even if they don’t.”

Private equity funds typically buy up public companies, turn them private in order to revamp businesses and sell them years later at a profit often to public shareholders. The carried interest deduction allows the private equity firms to sell investments held a year or more and have their investors’ profits taxed at a lower capital gains rate as opposed to the higher income tax rate of 39.5 percent.

Public policy groups say the tax treatment is unfair because it gives a massive tax break to wealthy private investors while average taxpayers must pay the higher rates. Private equity firms have argued that since the business holds the assets for more than a year in an attempt to rebuild troubled firms before selling them, the tax break actually creates jobs, giving an incentive for private equity firms to risk their capital and fix ailing businesses.