GOP leaders set for House vote on medical research bill

WASHINGTON – Republican leaders are ready to push through the House a compromise medical research bill that's prompted complaints from Democrats and consumer groups but seems all but certain to sail through Congress with momentum built by victories that it delivers for both parties and the White House.

The legislation envisions spending $6.3 billion over the coming decade, including $4.8 billion for National Institutes of Health research. States would get $1 billion over the next two years for preventing and treating abuse of addictive drugs like opioids, a surging problem in red and blue states alike, while the Food and Drug Administration would get $500 million to streamline approval processes for drugs and medical devices.

On the eve of the House's scheduled Wednesday vote, the White House sent a letter to lawmakers voicing strong support for the measure, all but guaranteeing congressional approval. Addressing worries by some Democrats, the letter said administration officials would act swiftly "to ensure that the funds in the bill would be disbursed quickly and effectively so we can begin to address these important public health challenges."

Senate consideration was expected next week.

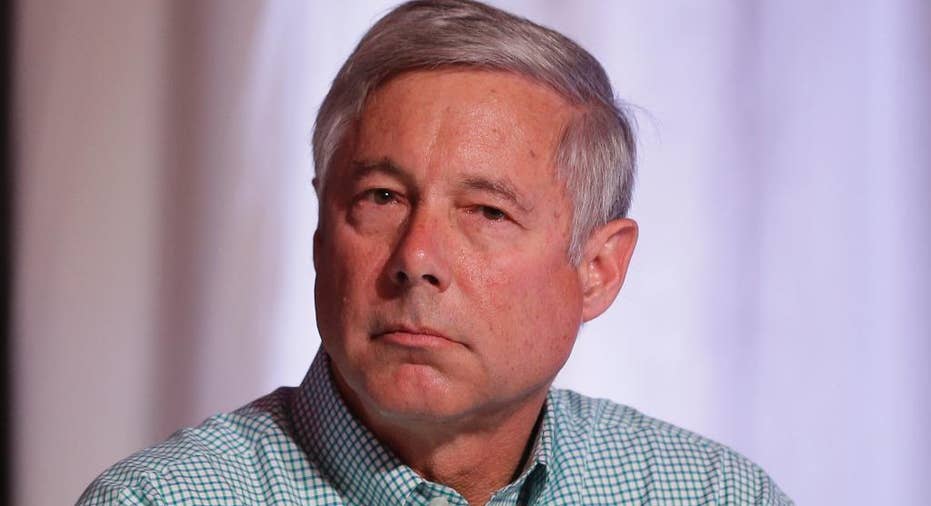

"We feel that we're on good footing," Rep. Fred Upton, R-Mich., chairman of the House Energy and Commerce Committee, said of the bill's prospects in both the House and Senate.

Underscoring the measure's bipartisan support, that panel's top Democrat, Rep. Frank Pallone of New Jersey, said he'd vote for the bill and its provisions would ease government approval of drugs "without sacrificing any safety."

The measure has won strong backing from the drug and medical device industries.

GOP leaders have trumpeted the bill as a key achievement for the post-election, Republican-led Congress as lawmakers prepare for Donald Trump to replace President Barack Obama in the Oval Office on Jan. 20. That looming transition has greatly reduced the leverage of Democrats, who would have preferred the bill to contain more money and greater consumer protections.

In two noteworthy wins for the White House, the bill includes $1.4 billion for Obama's precision medicine initiative, aimed at shaping treatments and care for people based on their genes and lifestyles. It has $1.8 billion for seeking a cure for cancer, a priority for Vice President Joe Biden, whose son Beau died of the disease last year.

The measure also contains provisions bolstering federal mental health programs, though it provides little money for those changes.

Democrats grumbled that though the bill designates funds for research, drug approvals and opioids abuse programs over coming years, it would take additional legislation to actually provide those funds. They were unhappy about savings that would pay for those initiatives, chiefly $3.5 billion to be cut from a public health program in Obama's health care law, which the GOP aims to repeal in its entirety.

Democrats and consumer groups were also upset with the streamlining of some Food and Drug Administration processes, including making it easier for pharmaceutical companies to win approval for some antimicrobial drugs and for fresh uses of some existing medicines.

Michael Carome, the director of Public Citizen's Health Research Group, said that while he was happy for extra research and anti-drug funds, "For us, the bad things are not an acceptable trade-off."

Among those who've said they will oppose the bill are two of the Senate's best-known populist figures, Sens. Elizabeth Warren, D-Mass., and Bernie Sanders, I-Vt.

On Tuesday, the liberal grassroots group Democracy for America emailed a fundraising solicitation warning, "If Democrats want to be the party of working families, they need to stand up to Republicans who want to shovel money into the pockets of shady drug companies."

In eleventh-hour talks, both sides said they had agreed to remove language that would have exempted companies from publicly reporting education-related gifts to doctors, such as textbooks. Firms must reveal many payments they give physicians, which critics say encourage doctors to prescribe products made by those companies.