As the lights go down on GE, don't blame Jack Welch for the darkness

Welch would have never let hundreds of billions of dollars in market value turn to dust

Fox Business Flash top headlines for November 11

Check out what's clicking on FoxBusiness.com.

There’s a temptation to blame the end of the once-mighty GE conglomerate on the late Jack Welch.

After all, he was the primary architect who built the company into a multi-layered behemoth that its founder, Thomas Edison, would not have recognized.

But it isn’t true. It ignores the messy corporate history of GE from the time Welch retired in 2001 until this week — when GE announced it will be broken apart into three separate units.

Yes, Welch pushed GE to its limits in terms of size and scale. But don’t forget, pushing companies to the limit was something that the market rewarded when such organizations were run well. Getting into entertainment, TV programming and dog insurance while churning profits through financial products and managing your earnings was particularly appealing to Wall Street . . . until it wasn’t.

And now Larry Culp, the new CEO, is betting he will be rewarded for doing the opposite. Because that’s what investors have wanted for some time now.

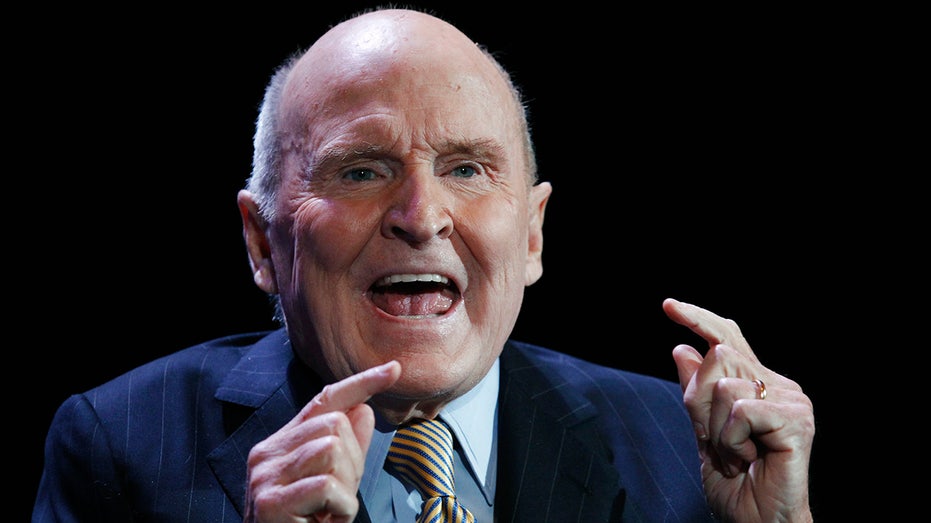

Former CEO of General Electric, Jack Welch, speaks during the World Business Forum in New York October 5, 2010. REUTERS/Lucas Jackson (UNITED STATES - Tags: BUSINESS) - GM1E6A602XI01

The question we should be asking is why in those intervening years GE’s management ignored what their investors wanted and instead chose the near stasis that nearly brought a great American institution to its knees.

The notion that GE’s parts were bigger than its whole is not a new one. I’ve been reporting for years that Welch was able to convince that the opposite was true as he drove the company to a market cap of $600 billion — the largest in corporate America just before he left as CEO.

GENERAL ELECTRIC CEOS: A SHORT BUT NOTABLE LIST

But then, not long after he was out, the herd went in the opposite direction.

Welch’s successor, Jeff Immelt, appears to agree that the GE conglomerate structure was obsolete not long into his tenure as CEO. In his book "Hot Seat," he attempts to convince the reader that from the day he took over in 2001, he was handed a business model that would make Rube Goldberg proud: Unaligned businesses with little or no synergies that he needed to make work and an urgency to dismantle much of it.

Immelt sold some stuff, namely NBC Universal. Yet he continued to rely on the conglomerate to try and make the whole really work even when evidence showed it wasn’t. He engaged in ill-fated deals (the Alstom Power deal blew $10 billion without much return) and continued to rely on GE Capital for support. Until GE Capital became an albatross during the 2008 financial crisis, as investors worried a company that made its bones in light fixtures, refrigerators, and jet engines was blowing it on underwater financial derivatives.

FILE - In this Monday, Feb. 22, 2016, file photo, then-General Electric CEO Jeffrey Immelt speaks at the annual IHS CERAWeek global energy conference in Houston. (AP Photo/Pat Sullivan, File)

Immelt had two chances, GE insiders say, to radically transform the company without much pushback from Wall Street. The first was after the 9/11 attacks, when the company faced severe pressure because the jet engine business — one of GE's biggest units— was under severe distress for obvious reasons.

OK, you can give him a pass for not wanting to blow up the house that Jack built not long after taking the CEO post, but why not after 2008, when the company needed government assistance to roll over its commercial paper because of the GE Capital exposure?

Certainly, Immelt knew things weren’t working; the stock price and earnings growth tell the story.

JACK WELCH WASN'T GOD, HE WAS HUMAN. THAT'S WHAT MADE HIM EVEN MORE REMARKABLE

Belatedly and with pressure from an activist investor, the GE board in 2017 had enough of Immelt and replaced him with a longtime company insider, John Flannery. It was more of the same, and Flannery was tossed a little more than a year after taking over.

Again, all Flannery had to do was listen to the same people I spoke with: Smart investors and many GE pros who liked both Welch and Immelt but saw how the company was floundering and someone needed to recognize the whole was worth less than the parts.

The current CEO, Larry Culp, now says he came to that conclusion after speaking with investors. But why did it take three years? Yes, Culp reduced overhead (no more corporate jets that got Immelt in trouble). He got out of more businesses.

But the markets weren’t that impressed. GE stock price recovered somewhat from its Immelt-Flannery lows, but consider the following: The crypto exchange Coinbase, which came public in the summer, already has a market cap of $70 billion. Compare that the GEs stock value of $117 billion after being around more than 100-plus years, and you’ll get the picture.

I know what you’re saying: The Coinbase comparison is a cheap shot since cryptos are a bubble phenomenon and GE will be here for years even if it’s a shell of its Welchian scale.

Yes, but investors also see value in Coinbase and a future; they’re seeing none of that in GE.

CLICK HERE TO READ MORE ON FOX BUSINESS

Welch, for all his empire-building faults, knew what the markets wanted, his career shows. He would have seen the tide was turning against his business model just as he saw the tide demanded GE get a lot bigger after years of being a steady-as-you-go electric company with a nice dividend.

He would have jettisoned stuff as fast as he built it up because he couldn’t take watching his stock crater for weeks, much less years. If you knew Welch, you also knew he had allegiance to the company way more than the trappings of the CEO job.

Market stock screen: istock (istock / iStock)

Immelt, Flannery, and yes, even Culp appeared to have a stronger stomach for ignoring investors while they tried to make something work that clearly wasn’t. Or they just liked running something big like GE. Either way, the belated breakup came at a high cost: Hundreds of billions of dollars of the market value turned to dust, one of the biggest destructions of wealth in recent financial history.

Sorry, Jack Welch would have never let that happen.