Save on Insurance, Compromise on Privacy

The high cost of health, life and auto insurance are serious issues in the U.S. Some think there's hope in "performance-based insurance," which provides policy rebates or reductions based on whether or not the policyholder meets or exceeds designated performance standards. When measuring performance, however, privacy issues emerge. The use of black boxes to track driver safety for auto insurance and apps that report lifestyle activities, such as diet and exercise routines for health insurance, are a couple of examples. Although advances in technology offer sci-fi-like monitoring capabilities, whether or not they'll be employed are two different things. In this interview, Richard Weber of the California Institute of Finance at California Lutheran University discusses performance-based policies, predictive medical tests and just how far consumers are willing to go to save money on insurance.

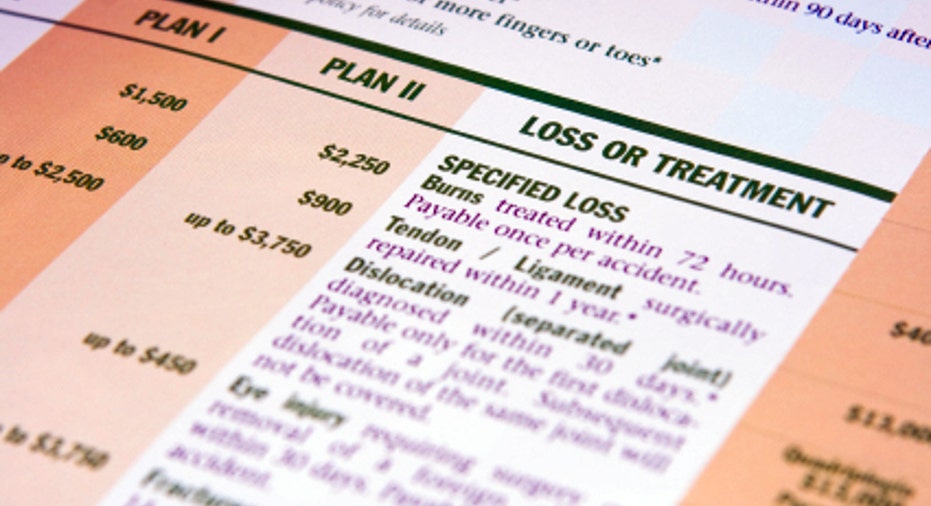

Performance-based insurance provides policy rebates or reductions based on whether or not policyholders meet or exceed designated performance standards. Do you foresee big business model disruption with a convergence of this technology with market forces, and how will this affect consumers?

I have no doubt that in the next few years, health policies will take into consideration factors such as those who lose weight, stop smoking and pursue a regime of physical activity. I think the question will be whether or not the consumer is sufficiently motivated to make these changes, and that will depend upon what the offered policy rate class looks like to begin with -- and whether the individual will receive the benefit of such changes -- or if they merely go to the credit of any employer or government program such as Medicare. And a key question is -- if I'm offered a preferred policy because of new behaviors -- what happens if I regress? In life insurance, once I qualify in a "preferred" risk class, I can subsequently begin to smoke, I could begin to overeat, I could get diabetes, I could fail to exercise and the insurance company is obligated to the original rate class determination.

Applying the analogy of accepting a black box in my automobile, the question for health or life insurance would be: If I subjected myself to periodic exams, would I, upon achieving a satisfactory score, receive a reward or perhaps, more applicable, a lower premium?

There are two considerations: One is industry acceptance and the other is the consumer's inclination and ability to work the system. I don't think the 50 states' Departments of Insurance who regulate this area would readily accept such dramatic changes, since they have generally resisted DNA testing as an underwriting factor. As far as consumers getting what they want, in a sense, that's already happening in some situations. For example, if I applied for life insurance and I'm offered a standard rating -- with the reason I'm not offered a more favorable rating because of my weight and lack of exercise -- I can change my lifestyle (lose weight and show physical signs of exercise) and then reapply to that or any other company and presumably get a better rate.

If affordable and accessible DNA tests could predict health factors a person is likely to manifest, those who can show they will have a relatively healthy future could request policy discounts. What barriers to this scenario do you see? What opportunities or challenges should insurance carriers consider?

First of all, I think that in the current environment, there would be an outcry from consumer advocates that would not allow that to happen.

On the other hand, employers are beginning to provide incentives and penalties for healthy lifestyle decisions. An employer providing health, disability and life insurance might pay a greater proportion of the overall premium for employees who make healthy choices and subsidize a lesser amount -- or provide less coverage -- for employees who maintain unhealthy lifestyles.

Incentive-based insurance began in the late 1960s when smoker/nonsmoker policy differentiation first took shape in underwriting life, health and disability policies. From there, insurance companies started to differentiate not just standard ratings but preferred, super-preferred and ultra-preferred. Ultra-preferred being, in theory, a status that could only be attained if both your parents are alive and healthy, you have never smoked, you have low body mass and fairly strict ratios of weight and height, and fairly low blood pressure and cholesterol, among other criteria. In effect, that transformed "standard" to substandard and made ultra-preferred and super-preferred the new norm for what was standard and standard-plus.

While I see more of this occurring in the life and disability types of insurance, I do not foresee any time in the near future that consumers would favor DNA or other objective testing-based criteria in employer-provided health insurance as well as for those receiving Medicare.

The recent health care law is offering states $100 million to reward Medicaid recipients who make an effort to quit smoking or maintain healthy weight, blood pressure or cholesterol levels. We may start to see exercise and wellness apps that demonstrate commitment to healthy living. Additionally, it may become possible to monitor healthy lifestyles via social media, such as Facebook pages. How likely is it that standard evaluations for life insurance policies, e.g. medical and blood tests, will include blanket requests such as: "May we use available data in your assessment?"

Again, I don't see DNA being accepted anytime soon. And with the recent backlash on information that social media sites are gathering without the user's express permission, I don't think this is going to be accepted in the next 20 years.

What types of technology do you believe people would be willing to adopt on a daily basis to save money on insurance?

I think that the auto insurance industry's black box is one of the first attempts of that approach. I think safe drivers will likely accept it and less-safe drivers will not. Again, this differentiates standard and better-than-standard so that people in the middle -- who are neutral in the making of rates -- are going to wind up paying more than they would have before such a rating system was adopted. And the black box is a good analogy in jumping from auto to life, health, disability and long-term care insurance. The essential issue is what that black box will reveal, and how will the new information be used? It has to be something different than what is currently in your medical records because those records are already part of the underwriting process. Now we are saying that additional information -- such as anything a DNA test would reveal -- would enter the underwriting process. I think that there is enough media concern, accentuated by movies and books on this very topic, that will postpone, for a long time, that type of data being used for any underwriting.

Special thanks to professor Richard Weber for sharing his insights. The questions for this interview were inspired from an article published by the futurist Jim Carroll, "Insurance 2020: Bold moves, turning concepts upside down!"