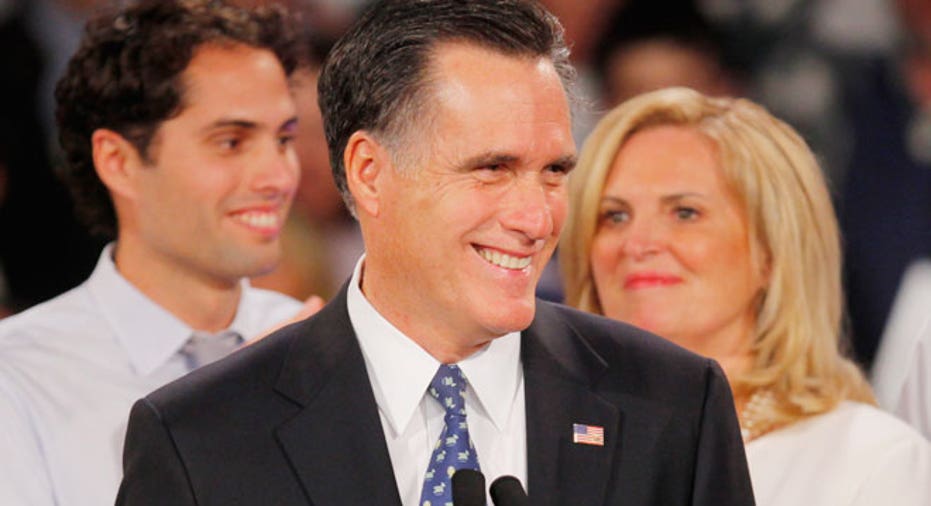

Romney's Big Controversy: Where's the Tax Return?

It is inconclusive whether GOP presidential contender Mitt Romney was a job creator or destroyer at his former company, Bain Capital. Bain is a private equity shop that doesn’t file financial statements with the Securities and Exchange Commission, and it does not track employment in its investments.

The bigger controversy for Romney has to do with taxes.

Specifically, three parts of the U.S. tax code lawfully juice private-equity executive payouts -- and it’s not just the fact that the executives pay their personal income taxes at lower rates than other executives do.

Where Are the Tax Returns?

Attacking Romney or Bain for restructuring companies is lame. Many reworked companies thrived and prospered, like Toys “R” Us, Burger King, Dunkin’ Donuts, Staples, Domino’s Pizza or Sports Authority.

The media is missing the fact that all of these revamped companies not only hired lots of people, they gave other small businesses who sell them goods or services a shot at success, too. Just as have businessmen like Larry Ellison, Bill Gates, Steve Jobs, Jamie Dimon, Michael Dell, or Warren Buffett.

Not to mention that restructuring organizations is as old as Jesus tossing the money changers out of the Temple.

But the broader controversy is likely the reason why Romney has yet to release his personal income tax returns, which every candidate since the Nixon era has done.

Three parts of the U.S. tax code legally enhance private equity executive payouts: Paying income taxes at the lower 15% capital gains tax rate versus the higher 35% income tax rate; borrowing heavily to do deals and then deducting on corporate tax returns the interest costs on those loans, thus juicing profits and executive payouts further; and getting lots of stock options from the companies they restructure.

The private equity guys, just like the leveraged buyout crowd, make ample use of the loan interest deduction. That’s because they tend to make heavy use of debt leverage to buy or invest in distressed companies to restructure them. They generally borrow in the range of 60% of the book value of their target companies.

Interest payments on those business loans are tax deductible, which lowers their IRS bills and in turn helps the bottom line.

Also, if a private equity firm raises money by selling bonds, they can deduct payments to bondholders, too, on their corporate tax returns.

Up to an estimated 20% of the returns from private equity deals come from lower tax bills, says the University of Chicago’s Steven Kaplan, a professor of finance there.

The Joint Committee on Taxation last year blasted the business-loan interest deduction for distorting economic activity, saying it encourages companies to raise investment capital through debt rather than equity.

Also, executives at private equity shops who restructure client companies or do leveraged buyouts often can get stock options from the newly bought or restructured companies they work on.

A stock option lets its owner buy stock in a company at a set price within a specified period. With those stock options in hand, private equity executives can make a lot of money if those revamped companies go public again or are sold in a merger.

Those executives, though, will have to pay income taxes on the gains they get from cashing in those stock options.

But there’s an upside for publicly traded restructured companies to pay their private equity helpers in stock options. They don’t have to deduct those stock options as executive pay from their corporate earnings, making their bottom lines look better to Wall Street.

And even though there’s no cash outlay for these stock options, companies can deduct them on their tax returns, lowering their tax bills and making their reported earnings look better, too.

Moreover, the private equity crowd pays much lower taxes on their personal income because executives at private equity shops tend to pay at the lower 15% capital gains tax rate, not the higher 35% personal income tax rate.

The way it works is, private equity executives typically get paid a 20% share of the firms’ profit from selling and restructuring companies, a cut that’s called “carried interest.” That, though, is treated as a capital gain, not as personal income under the tax law.

The Administration has tried to reform this private equity edge, but so far has not succeeded.

It’s a debate that has already gotten Stephen Schwarzman, chairman of the world’s largest private-equity firm, Blackstone, heaps of criticism. Schwarzman, who has endorsed Romney, has blasted any federal moves to restructure private equity tax bills.

Romney and Schwarzman started out in private equity during the Mike Milken-Ivan Boesky leveraged buyout movement of the 1980s. Romney worked with Schwarzman’s team on deals in the late ‘80s, making his company money.

In August 2010, when the Administration said it wanted to increase the tax bills on private equity income, Schwarzman likened this move to “when Hitler invaded Poland in 1939,” according to a New York Post account of a private meeting. Schwarzman reportedly later apologized for the comparison, but still criticized the tax hike proposal.

Next Up: Romney’s Economic Plan