The Three Scariest Letters for Bondholders: L-B-O

Some investors are hoping Dell’s (NASDAQ:DELL) $24.4 billion go-private deal will spark a return of the leveraged buyout craze that ended when the Great Recession popped the last credit bubble.

But don’t count bondholders among that crowd.

That’s because LBOs are among the scariest “shareholder-friendly” moves a company can execute from a bondholder perspective, saddling balance sheets with new debt, prompting credit downgrades and dramatically raising the risk of a default.

“It’s piling debt on top of debt. That’s the basic problem,” said Anthony Sabino, a professor at St. John’s University.

Just take a look at the polar-opposite reactions among Dell stakeholders to the LBO news.

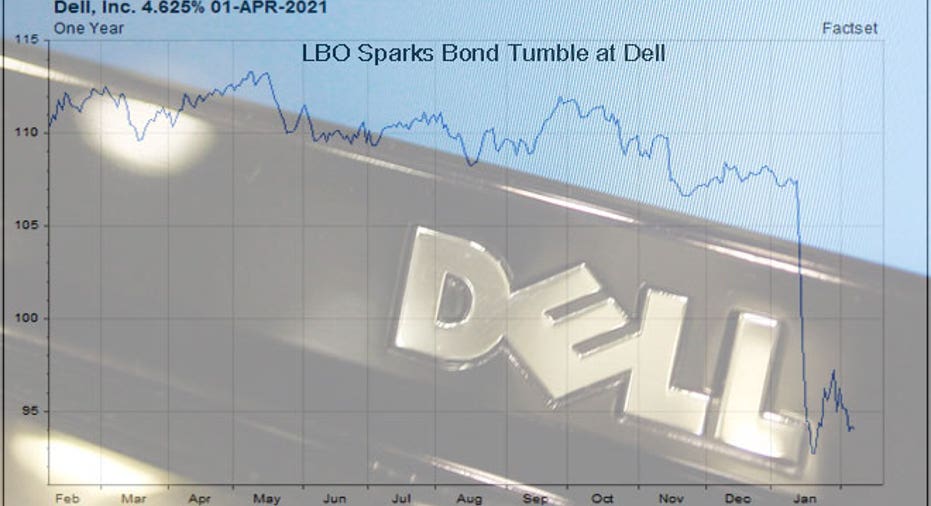

While Dell’s stock price has surged about 25% since reports of a potential takeover emerged last month, the struggling PC maker’s bond prices quickly headed south due to the fact the deal was going to be heavily leveraged.

According to Factset data, Dell’s 4.625% senior unsecured notes due April 2021 plummeted from over 105% of their par value in early January to just 94% by the time the deal was announced.

“In the current environment, there are many examples of debt-financed transactions designed to be shareholder-friendly,” Pat McCluskey, senior fixed income strategist at Wells Fargo Advisors (NYSE:WFC) wrote in a note, pointing to dividends and buybacks. “In our view, however, the most negative event for bondholders is the leveraged buyout.”

Debt-Heavy Transactions

The basic structure of LBOs, which were all the rage during the pre-Lehman credit bubble, require target companies to accumulate massive amounts of debt to buy out existing common shareholders by pledging their assets as collateral.

“This is not cash saved and cracking open the piggy bank. They borrow extraordinary amounts of money,” said Sabino.

In these complex transactions, existing bondholders are tossed behind the new ones in the capital structure, meaning they would be made whole later in the event of a bankruptcy, making their bonds less valuable.

At the same time, the extra borrowing costs reduce companies’ margin for error in the event business stalls due to another recession or some other event like a natural disaster.

“These things are usually so tightly wound that the least little change in the global economic perspective can not only be detrimental to your projections, it could utterly destroy them,” said Sabino. “That’s the danger lurking in the background that everyone has to be keenly aware of.”

Targets Grapple With Debt

The dangers of LBOs can be seen clearly in the cautionary tale of Energy Future Holdings Corp., which was formerly known as TXU Corp.

In the largest LBO on record, the electric utility company was taken private in February 2007 by Kohlberg Kravis Roberts (NYSE:KKR), Goldman Sachs (NYSE:GS) and TPG Capital (then known as Texas Pacific Group) in a $43.8 billion deal.

Just this week The Wall Street Journal ominously reported that Energy Future Holdings has hired restructuring lawyers as the company struggles with more than $40 billion in debt, which is an alarming ten times its Ebitda.

Dell already had $9 billion in total debt sitting on its balance sheet before the deal, a relatively high amount considering tech companies typically have very clean balance sheets. The PC maker may now need to add about $20 billion in debt to pay for the LBO.

“The last chapter of the Dell LBO has not yet been written but I would have cause for concern given the history of these things,” said Sabino.

Surviving LBOs

McCluskey warned that the Dell deal will likely prompt a credit downgrade.

“To essentially put the interests of one group of stakeholders over the interests of another, which is what happens in an LBO,” McCluskey said, “can result in long-term damage to a company’s credit ratings, which the company may find hard, if not impossible, to repair.”

To be sure, there are examples of LBOs where struggling companies go private and return healthy.

For example, Seagate Technologies (NASDAQ:STX), one of the world’s biggest makers of computer disk drives, was taken private in 2000 by Silver Lake Partners in a $20 billion deal. The company then raised $870 million in a 2002 IPO and briefly considered a second LBO in 2010 before its business rebounded.

Today Seagate is worth about $12.4 billion and its balance sheet has just $2.9 billion of debt, giving it a debt-to-equity ratio of 0.97, which is below the S&P 500’s 1.51 ratio.

"You see a 'successful' LBO is measured by going private, surviving, increasing profits and then going public again so you cash out. It's cyclical," said Sabino. “Nobody goes private to stay private! They LBO when they think the stock can be had cheaply and then cash out later for big money. It's a joke sometimes.”

Another Buyout Boom Ahead?

With record low interest rates and cautious optimism about the economy, some observers believe the Dell deal could spark a comeback in the M&A market, persuading more companies to take the LBO plunge.

“The debt markets are really wide open and very robust. They’re almost hungering for big deals like this,” said Soma Biswas, a private equity editor at Pearson’s (NYSE:PSO) mergermarket.

Biswas said one obstacle that may prevent a return of the LBO craze is that private-equity investors have urged firms not to pool together their equity because it increases exposure to just a handful of mega deals.

Still, as measured by the $20.6 billion of target net debt, Dealogic statistics show the Dell transaction is the 12th largest LBO on record and biggest since KKR took British drug-store chain Alliance Boots private in March 2007.

“This could be the bellwether for the next cycle in LBOs,” said Sabino. “All it takes is one big splash by an LBO and people say if works for them, it works for me.”

Largest Leveraged Buyouts in History(Click on Image to Enlarge)