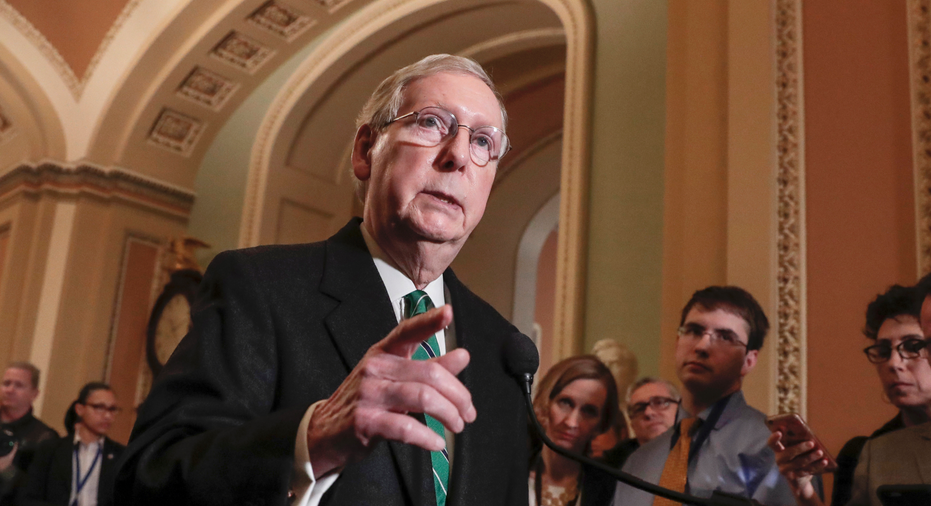

McConnell looks to complete hemp's comeback as crop

FRANKFORT, Ky. – Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell wants a full pardon for hemp.

The Kentucky Republican on Monday previewed legislation seeking to free the plant from its ties to marijuana and let it take root as a legitimate crop.

Hemp — marijuana's non-intoxicating cousin — would be removed from the controlled substances list under the bill he's offering, McConnell said. The result would legalize hemp as an agricultural commodity.

"We're going to give it everything we've got to pull it off," the Senate's top leader told hemp advocates in his home state.

The crop has been grown on an experimental basis in a number of states in recent years, and Kentucky has been at the forefront of hemp's comeback. Kentucky agriculture officials have approved more than 12,000 acres (4,800 hectares) to be grown in the state this year, and 57 Kentucky processors are helping turn the raw product into a multitude of products.

Growing hemp without a federal permit has long been banned owing to its classification as a controlled substance related to marijuana. Hemp and marijuana are the same species, but hemp has a negligible amount of THC, the psychoactive compound that gives marijuana users a high.

Hemp got a limited reprieve with the 2014 federal Farm Bill. McConnell helped push for the provision that allows state agriculture departments to designate hemp projects for research and development.

Since then, 34 states have authorized hemp research, while actual production occurred in 19 states last year, said Eric Steenstra, president of the advocacy group Vote Hemp. Hemp production totaled about 25,500 acres (10,300 hectares) in 2017, more than double the 2016 output, he said.

Supporters said the bill would bring more certainty for farmers, agribusinesses and investors looking at the crop.

"The goal of this new bill, should it become law, is to simply remove the roadblocks altogether," McConnell said. "It would encourage innovation and development and support to domestic production of hemp."

The crop, which once thrived in Kentucky, was historically used for rope, clothing and mulch from the fiber, hemp milk and cooking oil from the seeds, and soap and lotions. Other uses include building materials, animal bedding and biofuels.

Hemp advocates, who have fought for years to restore the crop's legitimacy, praised McConnell for putting his political clout behind the effort.

"This is a huge development for the hemp industry," Steenstra said. "Sen. McConnell's support is critical to helping us move hemp from research and pilot programs to full commercial production."

Brian Furnish, an eighth-generation tobacco farmer in Kentucky, has taken the plunge into hemp production. His family will grow about 300 acres (120 hectares) of hemp this year in Harrison County. He's also part owner of a company that turns hemp into food, fiber and dietary supplements.

Furnish said hemp has the potential to rival or surpass what tobacco production once meant to Kentucky.

"All we've got to do is the government get out of the way and let us grow," he told reporters.

McConnell acknowledged there was "some queasiness" about hemp in 2014 when federal lawmakers cleared the way for states to regulate it for research and pilot programs. There's much broader understanding now that hemp is a "totally different" plant than its cousin, he said.

"I think we've worked our way through the education process of making sure everybody understands this is really a different plant," the Republican leader said.

McConnell said he plans to emphasize the differences between the plants to Attorney General Jeff Sessions. The Trump administration has taken a tougher stance on marijuana.

The Department of Justice's press office declined comment Monday on McConnell's pending legislation.

McConnell said his bill would attract a bipartisan group of co-sponsors. He said the measure would allow states to have primary regulatory oversight of hemp production if they submit plans to federal officials outlining how they would monitor production.

In Kentucky, current or ex-tobacco farmers could easily make the conversion to hemp production, Furnish said. Tobacco production dropped sharply in Kentucky as the health hazards of smoking became clear and tobacco use declined.

Furnish said his family has reaped profits of about $2,000 per acre for hemp grown for dietary supplements, better than what they've made from tobacco, he said.

Kentucky Agriculture Commissioner Ryan Quarles said he hopes for hemp's legalization, saying it can "open the floodgates and we can see the true potential of this crop."