EPA chief defends spending on travel and soundproof booth

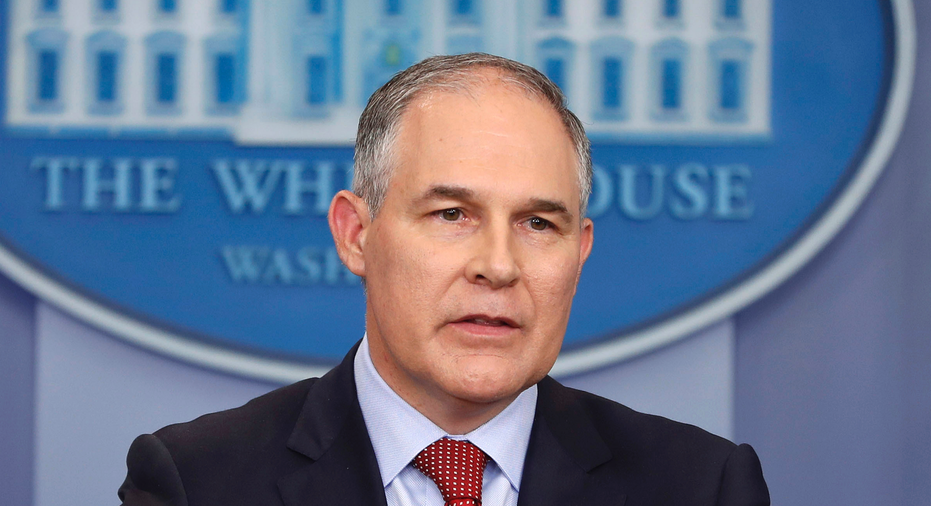

WASHINGTON – Environmental Protection Agency chief Scott Pruitt on Thursday defended his frequent taxpayer-funded travel and his purchase of a custom soundproof communications booth for his office, saying both were justified.

Pruitt made his first appearance before a House oversight subcommittee responsible for environmental issues since his confirmation to lead EPA in February. While his fellow Republicans largely used their time to praise Pruitt's leadership, Democrats pressed Pruitt on his proposed rollbacks of environmental regulations, his past statements denying carbon emissions are primarily to blame for climate change and his spending while in office.

The former Oklahoma attorney general is under scrutiny after expense reports showed he often leaves Washington on Thursdays and Fridays for appearances in westward states before spending the weekend at his home in Tulsa and then returning to EPA headquarters on Mondays. The EPA's inspector general is currently investigating whether Pruitt's trips violate EPA's travel policies and procedures.

"Every trip I've taken to Oklahoma with respect to taxpayer expenses has been business related," Pruitt said, before giving examples of meetings and environmental issues in his home state that he said required his personal attention. "When I've traveled back to the state for personal reasons, I've paid for it. And that will bear out in the process."

Rep. Diana DeGette, a Colorado Democrat, asked about the nearly $25,000 he spent on a custom soundproof booth for making private phone calls in his office — something none of his predecessors had.

Pruitt said the booth serves as a Sensitive Compartmented Information Facility, known as a SCIF, which typically are secure rooms used to house computers and equipment for communicating over classified government networks. Former EPA officials said that explanation doesn't make much sense.

There was already a SCIF at EPA headquarters in Washington where officials with the appropriate levels of security clearance can go to access classified information. EPA employees rarely deal with government secrets. The agency does occasionally receive, handle and store classified material because of its homeland security, emergency response and continuity missions.

Pruitt said he needed the booth to have a secure phone line with which he could communicate with the White House, located just a few blocks away.

"Cabinet level officials need to have access to secure communications," Pruitt said. "It's necessary for me to be able to do my job."

Committee Democrats also grilled Pruitt over what ranking member Frank Pallone of New Jersey called an "unprecedented assault on independent science" by purging academic experts from federal advisory boards and replacing them with industry representatives.

Pruitt in November appointed a new slate of members to 22 boards that provide input on issues such as drinking water standards and air pollution limits. For the chairmanship of EPA's Board of Scientific Counselors, he selected a former agency official who became an executive of a company that burns waste to generate electricity.

He also said he has barred from the boards current recipients of EPA grants or those in a position to benefit from them to avoid conflicts of interest. Twenty scientists on three committees have received $77 million in grants, which "causes a perception or appearance of a lack of independence in advising the agency on a host of issues," Pruitt told the subcommittee. Pruitt made no such prohibition for those who receive funding from industries regulated by EPA.

Rep. Paul Tonko, D-N.Y., asked for specific examples of an EPA grant recipient offering "conflicted advice." Pruitt said he could provide "many examples of scientists who received grants over a period of time that were substantial and it called into question that independence, and we addressed that through the policy that we implemented."

Tonko said Pruitt's EPA was ignoring scientific consensus through its downplaying of climate change and its approach to regulation and eroding staff morale by censoring experts.

"I believe EPA has all the signs of an agency captured by industry," he said.

___

Flesher reported from Traverse City, Michigan.

___

Follow AP environmental writer Michael Biesecker at http://Twitter.com/mbieseck