California revenue is growing. So why the talk of deficits?

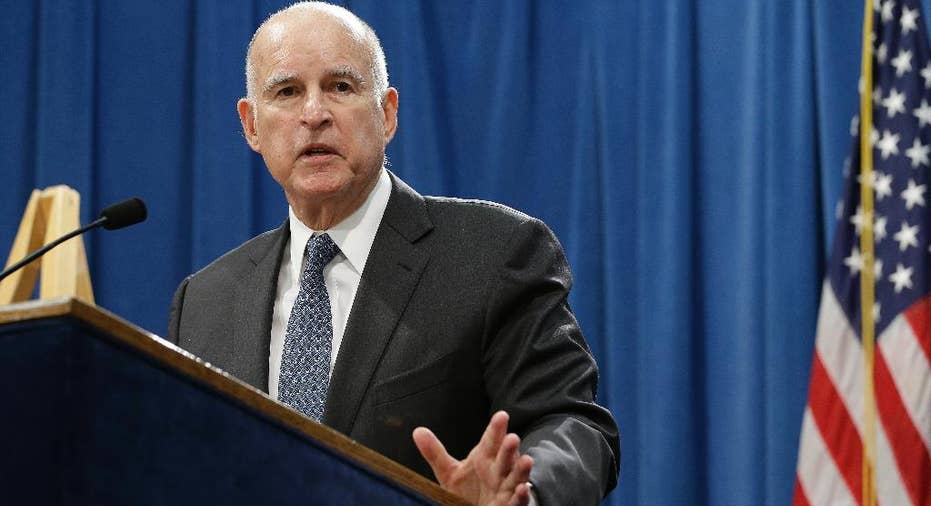

SACRAMENTO, Calif. – California's economy is expanding and voters just approved billions of dollars in tax increases, yet Gov. Jerry Brown this week projected a budget deficit for the first time in four years and called for spending cuts.

So what's going on?

The paradoxical budget picture is a result of revenue growing more slowly than economists had predicted after years of rapid increases from a hard-charging economy. While Brown expects revenue to be up 3 percent next year, Brown and lawmakers assumed revenues would be even higher when they planned the current budget, and they spent accordingly. Costs are higher than expected, too.

Lower revenue and higher costs mean the state has approved spending money that Brown doesn't think it will collect. He is proposing to cut $3.2 billion allocated to education, state building construction, affordable housing, college grants and child care providers.

"The red always far outweighs the black, and the years of surplus are very few in number and very modest, and the deficits are much larger in magnitude," Brown, a Democrat, told reporters when he released his opening budget proposal on Tuesday. "And that really is the challenge of California."

Brown's administration says California's three biggest income sources — personal income taxes, sales taxes and corporate taxes — are all coming in below projections.

That's because recent growth in wages has been dominated by workers at the lower end of the wage spectrum who pay less in taxes, according to the Department of Finance. Many new jobs are going to people new to the workforce or re-entering it, who tend to make lower wages, and minimum wage increases are raising labor costs.

The higher labor costs, combined with fears of lower earnings in the coming year, are diminishing corporate profits and the taxes they pay.

And sales taxes are depressed by high costs for housing and health care — expenses that don't incur sales tax but eat up consumers' disposable income and crowd out other spending.

Meanwhile, costs are rising.

For the current budget year, Brown and the Legislature approved $6.2 billion in new optional spending on programs they care about; about $700 million of it is for ongoing costs for universities, state workers, the courts and prison system, and social services. They also under-calculated how much it would cost to operate Medi-Cal, the publicly funded health plan for the poor, by about $1.8 billion.

Brown could also be wrong. The administration's revenue forecast for the next budget year is $4.1 billion less than the Legislature's estimate released two months ago, which projected a surplus.

"The state has a history of being off on projections," said Jeff Cummins, a professor at California State University, Fresno and author of a book on California's budget. "It's notoriously hard to get it right. ... There are so many variables at play when you're trying to make those projections that it's really hard to be accurate."

Republicans say the problem isn't with revenue but with spending.

Despite the recent revenue slowdown driving Brown's current deficit projection, state revenue is up $36 billion since the worst of the budget bleeding that followed the Great Recession. Some of the extra money is thanks to robust economic improvement that drove up wages and employment, and some is the fruit of voter-approved tax increases on high-income earners.

About two-thirds of the $36 billion has gone to required education spending; by law, about half of state revenue must go to K-12 schools and community colleges. Per-student spending in the governor's budget proposal is up $3,900 since 2011-2012.

The state's decision to expand the Medi-Cal program, as allowed under President Barack Obama's Affordable Care Act, will cost $1.6 billion from the general fund in the next budget. While the federal government initially covered all medical costs for newly eligible people, the state is now responsible for covering 5 percent.

Brown and lawmakers have also expanded higher education funding. Costs are up for public-employee pensions and retiree health care costs. The higher minimum wage and collective bargaining agreements have increased state labor costs.

"Just last November, California voters approved an additional $10 billion of new taxes to line our government's pockets, yet the governor and the Democrats have managed to spend $2 billion more than the state is projected to collect," Assemblyman Travis Allen, R-Huntington Beach, said in a statement.