At the EEOC, harassment cases can languish for years

WASHINGTON – The federal agency handling workplace harassment complaints has become a crowded waystation in an overwhelmed bureaucracy, with wait times often stretching years. And as the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission takes on renewed significance in light of the growing #MeToo movement, lawyers worry the increased caseload will lead to even longer delays.

A federal worker filing a complaint with the EEOC last year waited, on average, 543 days for resolution. But cases can drag on much longer, often forcing employees to choose between enduring discrimination or abandoning their careers.

Employment lawyers say the cash-strapped agency is doing its best. But they also say the uptick of sexual harassment cases being brought to the EEOC could mean longer wait times.

"We are totally inundated," said Cathy Harris, a Washington-area employment attorney whose practice focuses mostly on federal employees. "I don't think there's more discrimination; I think people are just encouraged to do something about it now."

While the omnibus spending bill Congress passed last month gives the EEOC a $15 million budget boost, the commission is still without permanent leadership. President Donald Trump's choice to lead the five-person commission, corporate attorney Janet Dhillon, has inspired fierce criticism from civil rights groups. Neither Dhillon, who is married to a White House attorney, nor Daniel Gade, nominated for a seat on the commission, have come up for Senate confirmation votes.

The #MeToo movement, which began last fall, has empowered victims of sexual misconduct to come forward with complaints.

The EEOC operates on two parallel tracks: one for private sector workers, and one for federal employees. Both are struggling.

In 2017, the average wait time to resolve a private sector complaint was about 295 days.

The agency receives so many complaints that its 549 investigators must prioritize cases deemed likely to be strong.

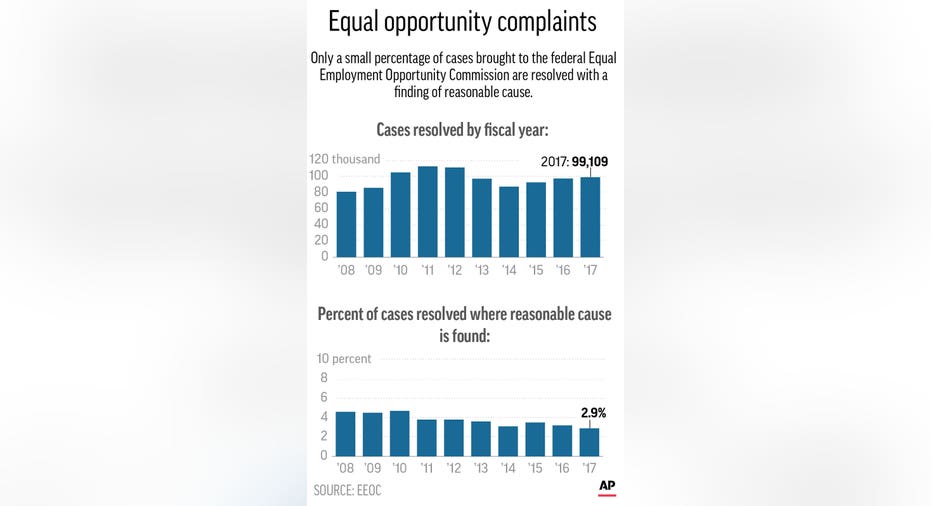

Last year the agency closed 99,000 cases. In 70 percent of those cases, investigators determined there wasn't evidence immediately available to make a finding that discrimination occurred. But many were dismissed without a full or even cursory investigation; last year, just 2.9 percent of all resolved cases were found to have reasonable cause.

"We're devoting our resources to charges where there seems to be more likelihood to find discrimination that we can attempt to resolve, and spend fewer resources on charges where it appears less likely to find discrimination," said EEOC Project Manager Nicholas Inzeo, who oversees the agency's 53 field offices.

Some lawyers say dismissing complaints without full investigations can discourage workers from pursuing their claim in court.

"It's easy to say there's no reasonable cause if you don't do an investigation," said Richard T. Seymour, an employment lawyer.

Attorney Jacob Small said many workers don't want to go through the lengthy, emotionally draining and very public process of filing a lawsuit.

"So many people realize it's just easier for them to move on or to take a very small settlement that doesn't compensate them for the harm they've actually suffered," he said.

The agency's handling of federal employee complaints often takes even longer.

Federal employees must first file a complaint with their agency's equal employment office, which conducts an investigation. The employee may then file a lawsuit or request a hearing with an EEOC administrative judge.

The average time to resolve a federal complaint with the EEOC is about a year and a half, though complaints filed in busy offices can take much longer. In 2016, just 73 judges were tasked with handling roughly 20,000 cases. By the end of the year, 13,500 were left in the queue.

"I have some cases that have sat on judges' desks for five years with no hearing date in sight," said Rosemary Dettling, the founder of the Federal Employee Legal Services Center.

Dettling said some clients endure years of harassment and retaliation. Others look for other jobs.

"Our clients' suffering is real," she said. "Some leave the jobs they love, just to escape."

In 1993, Ann M. Garcia was an ambitious 34-year-old agent at the Drug Enforcement Agency with dreams of going overseas. But headquarters had told her that she shouldn't stray far from home because her husband might get bored and leave her.

She filed a discrimination complaint with the EEOC alleging her employer illegally denied female agents promotions and foreign assignments because of their gender. An agency judge ruled in her favor — in 2011.

She was 52 and had retired, along with more than 70 other female agents who'd joined her complaint. While the action was pending Garcia did receive a foreign assignment, but many of the others didn't, she said.

"All the emotional distress — the anger, the anxiety," Garcia said. "They say time heals everything. But what happens if something just never ends?"

Protracted cases can also prevent harassment victims from moving on and cause memories to become less reliable.

"Try to litigate a case where you're taking depositions two or three years after the fact," said attorney Les Alderman. "Those fuzzy memories turn into generalities. The delays really, really hurt victims."

Inzeo said the agency is in the process of hiring at least six more administrative judges to ease the burden. Currently, judges each can handle up to 200 cases a year.

Inzeo disputed that cases typically drag on for years, but said he recognizes the frustration many feel over long wait times.

"We are working on projects that will reduce the amount of time, reduce the complexity of it and make it more efficient, for the parties and for us, and reduce inventory, and help us get through the cases more quickly," he said.

Despite its problems, Harris, the Washington employment lawyer, stressed that the EEOC is an invaluable resource.

"They can literally change people's lives and remedy harm," she said. "It's an agency with an incredible power to heal wounds. It's a wonderful system. It's just underfunded, and completely broken."