Why State-Run Health Exchanges are Faring Better

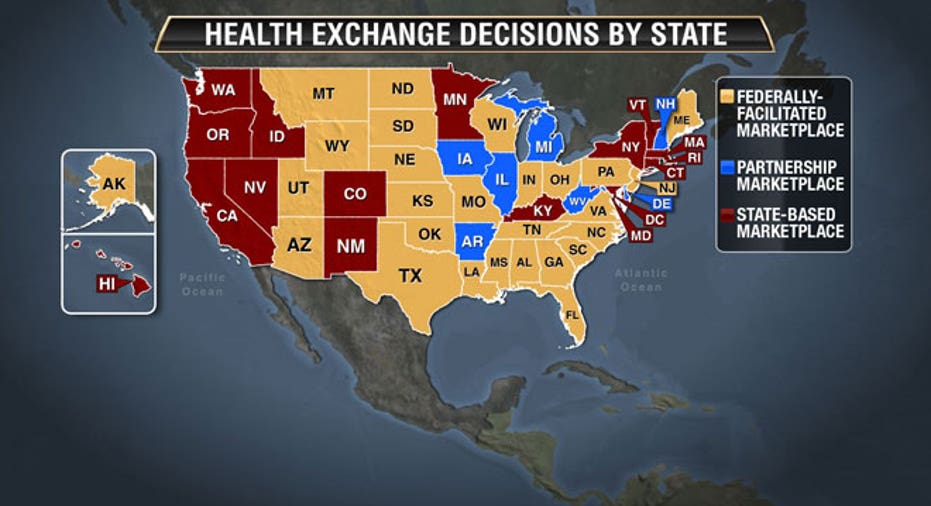

Seventeen states currently run their own health insurance exchanges, 27 states have a federally-run marketplace and six states have a hybrid of both. But when the Affordable Care Act was designed, it was wrongly assumed that the road most states would take would be creating their own state-run health exchange. Now, the state-run exchanges are doing better right out of the gate, a lot better, and this may have lasting consequences.

"They just didn't contemplate that the feds would have to run over half of the states," said Dan Mendelson, CEO of Avalere Health, a consulting company that’s been tracking insurance marketplaces. "And while the federally-run exchanges are behind, the state-run health exchanges have done their work -- embracing the program, engaging their communities, advertising…."

Believing each state would want to design its own system was not without reason: there is nearly $4 billion in federal funding grants under the ACA, almost of all which goes specifically to the states who run their own exchanges. There is also a certain amount of sovereignty and added support in having a self-designed exchange in place, said Sarah Dash, a research fellow at Georgetown’s Center on Health Insurance Reforms.

"States that run their own exchanges have gotten an incredible amount of support," said Dash. "The feds [and their federally-run state health exchanges] have had to use their own resources."

Since its Oct. 1 start date, the federally-run interface system, healthcare.gov, which cost more than $400 million to build, has not been working correctly -- with the website crashing, users unable to log in and people struggling to get quotes without going through a login process. (CGI Capital, which was the ACA’s biggest contractor, was awarded $94 million in 2011 to build the site but was paid substantially more as costs accrued.)

"I think we will see better enrollment in the states that run their own exchanges, and that will play out for years to come,"

"Their online system doesn't work" said Mendelson, who pointed out that it was in stark contest to state-run websites like California’s (which has been running almost glitch-free). “The reason for all of this is completely political. Governors, like Rick Perry of Texas, who did not welcome ACA expansion and had a profound moral problem with it, chose to have the feds run their states health exchanges."

It's not just the websites themselves that are generally better in state-run exchanges, insurer participation is also an issue.

"There are exceptions but overall, there are more insurers working with state-run exchanges," said John Holahan, an institute fellow at the Urban Institute’s Health Policy Center.

Holahan said because the states that run their own exchanges got started earlier and had more enthusiasm surrounding the program, they will likely offer more options for the consumers.

He also pointed out that geography plays into it. States that have a smaller population and that are dominated by one or two insurance agencies are not enticing to other insurers, which know they will not have a big market in places like Montana and Wyoming (which, according to the Department of Health and Human Services has the most costly coverage -- and that happens to be federally run; state-run exchange Minnesota is said to have the least expensive coverage).

A big upset since the ACA rollout has been the realization that some of the nation's most impoverished citizens will not be getting any coverage. As The New York Times has reported, an estimated eight million Americans are ineligible for aid because Medicaid was not expanded in their states. (This happened after the Supreme Court struck down a key Medicaid provision within the ACA that would have penalized states by denying them federal funds if they didn't expand coverage.)

And it just so happens that all of the states that did not expand are now federally run, which just adds another layer of unneeded problems for those exchanges.

"Most of the states running their own health exchanges did expand Medicaid for the lowest-income bracket," said Dash. "So, if you make $15,000 or less, you will have coverage.”

But for states like Mississippi, whose health exchange is federally run and whose ceiling for Medicaid is $3,000 annually, there will be no health insurance between the $3,000 mark and $15,000 mark. (At the $15,000 mark, Dash explained, the federal tax credit, one of the hallmarks of ACA, kicks in.)

"What the Affordable Care Act is really doing is leveling the playing field," said Mendelson, who explained ACA will not make health-care costs cheaper overall. For a young person who has never had health issues, coverage will probably be more expensive but for those who are older or have pre-existing conditions, it will make insurance costs more reasonable. (A Commonwealth Fund survey published in 2009 found that people with health problems found it "very difficult" or "impossible" to find a plan with coverage, compared with about one-third of respondents without a health problem.)

The Affordable Care Act will reportedly cost individuals an average of $3,000 a year and while the government has yet to release enrollment numbers on the federally-run exchanges, an estimated 38,000 have signed up for new health plans in state-run exchanges, according to state data tabulated by The Wall Street Journal.

And, there are no numbers yet determining whether it will be better to live in one state versus another because of better health care provisions.

But, said Mendelson, "I think we will see better enrollment in the states that run their own exchanges, and that will play out for years to come."