The blame game, ransomware edition: Who's at fault?

NEW YORK – From governments to individuals, there's plenty of finger-pointing going on following the latest global cyberattack.

Who's being targeted for blame? There's Microsoft, whose ubiquitous Windows operating systems were compromised after attackers exploited a security hole.

Then there's the U.S. government, whose Windows hacking tools were leaked to the internet and got into the hands of cybercriminals.

There are the companies, universities, hospitals and other organizations that didn't install Microsoft's fixes and take other precautions, such as backing up data.

Lastly there are, of course, the attackers, who kidnapped precious data and demanded ransom be paid.

"You can point a lot of fingers, but I think given that this was not a zero-day vulnerability (for which no patch is available), the people hacked are to blame," said Robert Cattanach, a partner at the international law firm Dorsey & Whitney and an expert on cybersecurity and data breaches. "Still, the NSA can't be very proud of this. Microsoft can't be proud."

Here are some of the key players in the attack and what may — or may not — be their fault.

— THE NSA

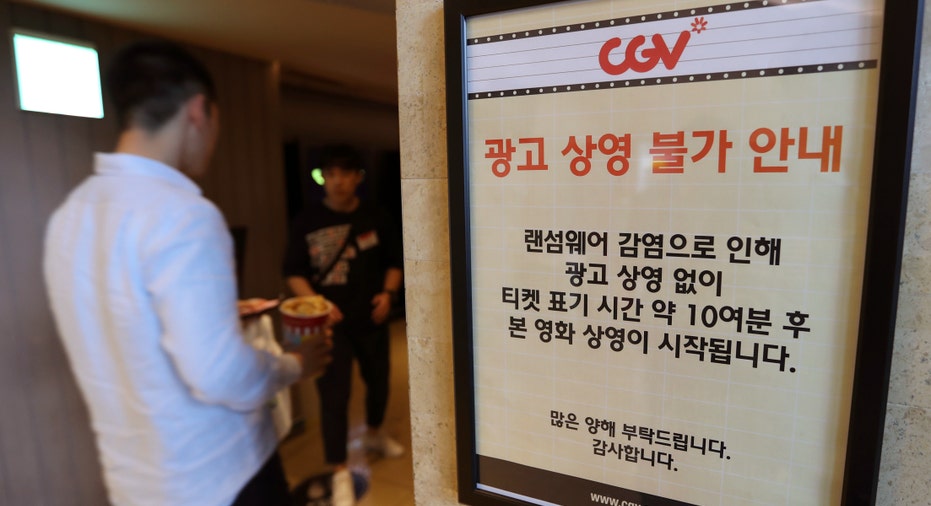

"WannaCry," as the ransomware is known, uses a Windows vulnerability originally identified by the NSA, according to security experts. So it makes sense to assign some responsibility to the NSA — the attackers didn't come up with this security hole on their own, after all.

On top of that, critics say, the government didn't notify companies like Microsoft about the vulnerabilities quickly enough. Brad Smith, Microsoft's top lawyer, criticized U.S. intelligence agencies for "stockpiling" software code that can be used by hackers.

"We have seen vulnerabilities stored by the CIA show up on WikiLeaks, and now this vulnerability stolen from the NSA has affected customers around the world," wrote Smith in a blog post on Sunday.

The ACLU, meanwhile, urged Congress to pass a law requiring the government to disclose vulnerabilities to companies "in a timely manner," so that they can patch them as soon as possible. Microsoft did issue patches for the vulnerabilities before the attacks took place, but not everyone downloaded them.

Avivah Litan, a cybersecurity analyst at Gartner, agreed that the government is "is negligent not doing a better job protecting companies," but added that it's not like "you can stop the U.S. government from developing cybertools" that then work as intended.

— MICROSOFT

It's hard to blame Microsoft, Litan said, since it issued fixes and generally did what it should.

Still, it was Microsoft that wrote the exploitable software to begin with. And, while the company did issue early fixes for its newer operating systems, patches for older Windows systems were only issued free of charge over the weekend, after the attacks began.

Microsoft should know that there are people, small businesses, schools and hospitals that still use older version of Windows, such as XP (which came out in 2001). And just as they are unlikely to pay for an upgrade to their operating systems, they may not want to — or be able to — pay for security fixes.

"Clearly having the vulnerability be in Microsoft software was one of the key elements," said Steve Grobman, chief technology officer of McAfee, a security company in Santa Clara, California. He noted, however, the complexity that can be involved in patching a security hole.

— COMPANIES, HOSPITALS, OTHER VICTIMS

It's hard not to engage in a bit of victim-blaming in this situation, especially because security experts say the attacks could have been prevented. No company — or hospital, or university, or individual — asks to be the victim of cybercrime, but there are also things companies can do to prevent the attacks from succeeding.

This includes whitelisting certain websites and software so only approved programs can run on a computer, or disabling administrative privileges on a company's machines so that only the IT department can download programs. Multiple backups also help. If you have a backup, there's no need to pay ransom for your data.

"It's not rocket science," Litan said.

Michael Mitchell, spokesman for Oreo cookie maker Mondelez International, said the company is not aware of any incidents from the attack, though it did alert employees. Asked what the company is doing to prevent such exploitations, he cited "basic IT security blocking and tackling."

"The operating systems on our computers and software downloads are managed centrally so that regular users cannot download executable files from the internet without administrative rights," he said in an email. "Software updates and security patches are pushed to us as needed so that we are using the most current approved versions of software on our computers."

— THE CRIMINALS

For all the worldwide chaos they have caused, the ransomware attack's perpetrators have reportedly made little more than less than $70,000, according to Tom Bossert, assistant to the president for homeland security and counterterrorism.

They exploited a perfect storm of factors — the Windows hole, the ability to get ransom paid in digital currency, poor security practices — but it's unclear if the payoff, at least so far, was worth the trouble. If they caught, that is.

__

AP Food Industry Writer Candice Choi contributed to this story.