It’s Official: We Are in a Tech Bubble

As a survivor of the first dot-com bubble, you might say I’m particularly sensitive to the suggestion that we may be heading toward another. Maybe skeptical is a better word. I mean, how can an industry full of so many brilliant and innovative people – an industry I was once a proud part of – make the same eminently self-destructive mistake twice?

They can. And they are.

Never mind what all the pundits say: Sure, there are similarities, but it’s different this time. Back then we had companies getting funded on nothing but a concept. We had startups running Super Bowl ads, going public, and quadrupling on the first day of trading without selling a single anything to anybody.

Well sure it’s different this time. It’s been 14 years, almost to the day, since the Nasdaq peaked at 5,132 before plummeting back to earth. Fourteen long and eventful years. And remember what they used to say about Internet time, that it accelerates everything? So that must be something like 210 years in Internet time, right?

Or maybe that’s dog years. I always get those two confused.

Of course not everything’s the same as before. But the underlying causes are, not to mention some pretty impressive signs staring us right in the face. And perhaps the most telling sign is how hard all those pundits are working to prove that, this time, it’s for real. That this time, we’re not in a bubble.

Here’s why I think they’re all wrong.

Don’t overlook the obvious.

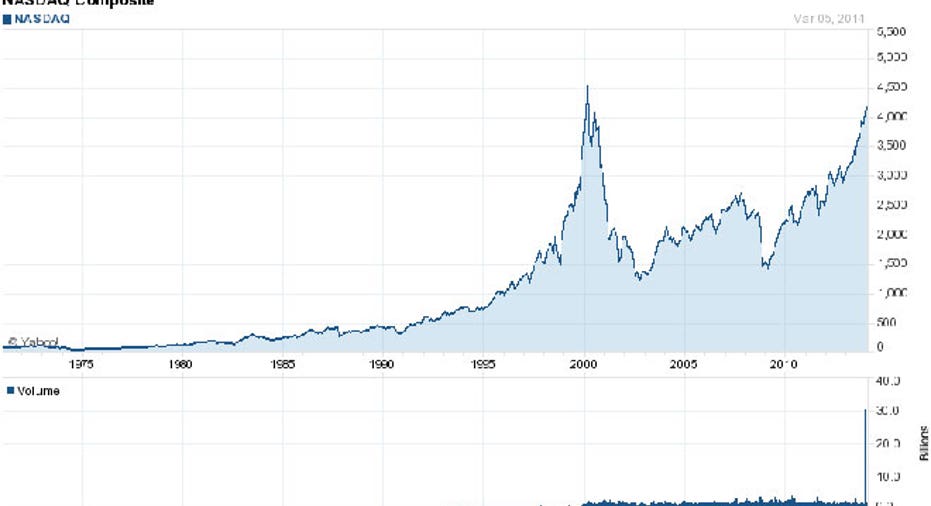

The Nasdaq skyrocketed by more than 4,000 points over the five-year period leading up to its all-time high on March 10 of 2000.

Fast forward to today. Over the past five years, the Nasdaq has risen more than 3,000 points. It’s less than 800 points shy of its lofty peak in the dot-com bubble. And we only need an 18% gain to get there – about the same rise we’ve seen in just the past six months.

Public valuations for Internet and related hot tech companies are, once again, unjustifiably sky high. LinkedIn’s (NYSE:LNKD) price-to-earnings ratio is 942. Guidewire Software’s (NYSE:GWRE) P/E is 782. Amazon’s (NASDAQ:AMZN) is 632. Netflix’s (NASDAQ:NFLX) is 245. Facebook’s (NASDAQ:FB) is 116. Twitter (NYSE:TWTR) has a $30 billion market cap with no earnings and whopping price-to-sales multiple of 44.

Not to mention the dozens of startups that went public over the past year or two that, like Twitter, have never made money and boast otherworldly price-to-sales multiples in the high double-digits.

Valuations of private companies are even more pumped up. A few weeks ago, Facebook bought 4-year-old WhatsApp for $19 billion – a record for a Silicon Valley company. And the messaging app has just 55 employees and a few million dollars in revenue.

Last November, Snapchat’s 23-year-old CEO Evan Spiegel turned down a $3 billion all- cash offer from Mark Zuckerberg and company. Rumor has it that Google (NASDAQ:GOOG) offered even more. Clearly, the messaging startup’s VC backers – IVP, Benchmark, and Lightspeed – are expecting a far bigger return for their investment.

Tech IPOs are just beginning to heat up. According to CB Insights, 600 startups in the IPO pipeline have raised more than $55 billion – that’s nearly $100 million apiece. And 47 venture-backed companies – including Palantir, Pinterest, Box, Spotify, Fab, and Square – are valued at more than a billion dollars.

And those are just the obvious signs.

Welcome to Crazytown

The hot air that makes a market bubble grow comes from CEOs, VCs, investment bankers, analysts, and traders using creative valuations to justify what they’ve done or are about to do. They do that by making comparisons that don’t make sense and using questionable metrics that assume markets are infinitely elastic balloons.

Oh yes they do.

Wall Street Journal business editor Dennis Berman recently provided us with a glaring example of how this sort of insidious logic works. He aptly describes his initial assessment of the Facebook WhatsApp deal as, “Not just crazy. Crazytown.”

Then, in what I assume was an attempt to figure out how Zuckerberg justified a valuation of $19 billion for a tiny startup – albeit one with 450 million users – Berman employed a fantastically creative, if not convoluted, methodology.

In a nutshell, he compared the Facebook deal to Verizon (NYSE:VZ) paying $130 billion to Vodafone for its 45% stake in their Verizon Wireless joint venture. Then he related the value of Verizon’s subscribers to that of WhatsApp’s users and concluded, “It’s still crazy. Just not as crazy as I thought.”

I’m guessing that “Not as crazy as I thought” is the next town over from “Crazytown.” I’m sure they at least share a border.

In reality, Facebook can afford to spend 11% of its already sky-high $180 billion market cap in the hope of capturing nearly a billion eyeballs, so the valuation doesn’t have to make sense to the social network. Zuckerberg is just playing with funny money.

The comparison of Verizon’s nearly 100 million subscribers that spend about $70 a month to unmonetized users of a messaging app makes little sense. And Verizon is an established market leader with essentially two competitors while WhatsApp competes with dozens of other messaging apps. The competitive barriers are in now way comparable.

The flaw in the ointment

And that leads us to the most tragically flawed assumption that’s pumping up all the crazy public and private valuations of Internet companies: the assumption of a perfectly elastic market with infinite growth potential when, in reality, hundreds of Internet companies compete for the same sets of eyeballs and limited disposable income.

And they will not all somehow magically manage to monetize these ridiculously high valuations at some point in the future.

This is exactly how bubbles occur. Everyone assumes the other guy knows something they don’t know and that becomes the new assumption that future valuations are based on. Analysts bless the deals, investors buy, and everyone cashes in. For a while.

Berman’s final words are telling: “There's been so little precedent for business at this scale that we have a hard time simply comprehending all of this. I'm still learning, too.”

I hear that sort of thing a lot these days, mostly from people who were still in college when the dot-com bubble burst. How there’s no precedent. How, this time, it’s different. How fundamentals like revenues and profits don’t apply here.

It reminds me so much of how the insatiable demand for Internet bandwidth was supposed to justify the sky-high valuations of all the fiber optics, communications, and Internet companies in the first dot-com bubble, it sends a chill down my spine.