Capturing Solar Energy in Space for the World's Remotest Region

It may sound like a 1970s sci-fi flick starring the likes of Darth Vader or Captain Kirk.

But as the debate rages on in Washington over green energy, one former NASA engineer has an intriguing solution: capture solar energy in space through a network of intelligent mirrors and transport it back to Earth through a microwave beam.

The vision of solar power in space has been around for decades, however, John Mankins, the former head of Advanced Concepts Studies at NASA and now president of Artemis Innovation, says the project is finally feasible thanks to advances in solar tech and space travel.

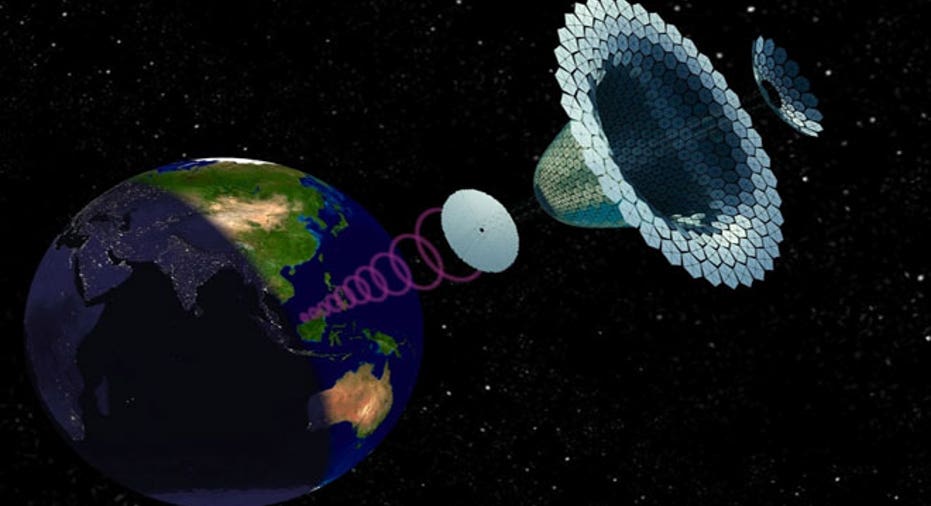

His goblet-shaped idea dubbed SPS-ALPHA (Solar Power Satellite via Arbitrarily Large Phased Array, if you want to get technical) would be comprised of thousands of intelligent computers working together in high orbit to capture and transmit the sun’s rays to be used as energy.

“SPS-ALPHA is a biologically inspired architecture, analogous to a hive of bees, or a colony of ants,” Mankins said in a detailed 100-page report on the concept. “A very large number of modules will be assembled to form a single enormous satellite.”

The satellites would spend their lifetime collecting the sun's rays through individually pointed thin-film mirrors. Energy would be converted across a large radio frequency aperture and transmitted via a microwave beam to receptors on Earth.

The entire project requires just minor innovations, which means its development is, feasibly, capable within 15 years notwithstanding any outstanding hurdles. Mankins sees the first two small-scale prototypes requiring about three years and $50 million to build, and the larger, in-space prototype taking another decade and $3 to $4 billion.

“The innovative advanced concept described here is a new approach to enable a technically feasible, economically viable and programmatically executable solar power satellite,” he said.

The World's Remotest

The former NASA researcher doesn’t expect SPS-ALPHA to replace today’s energy sources but acting instead as complimentary, deploying on an as-needed basis to remote islands, disaster areas or helping to offset the traditional grid if it were to be taken temporarily offline due to a storm or catastrophe.

“Between now and 2045 total electricity consumption on Earth is projected to double – and by 2100 it’s projected to double again,” Mankins said.

Each receptor would collect the equivalent of a tenth of 1% of the entire U.S. energy requirement. But the benefit is that the receptors – each a few kilometers long -- could be built relatively quickly once the satellites are deployed.

The satellites themselves would be able to turn in any direction so that emergency energy can be zapped to the far reaches of the world on command.

“These are all places that are geographically isolated -- the price of energy is two or three times the price in the Continental U.S.,” Mankins said, pointing to regions like Northern Canada, Hawaii and Indonesia. “From space, we can deliver power directly to” them.

Meanwhile, the receptors, which must be large enough (five to 10 kilometers) so that the beam can be diluted and harmless to people on Earth, would be made from a thin film that is 80% transparent.

It would allow for the passing of rain water and sunlight, enabling regular vegetation to thrive underneath. The receptors could be installed over a large stretch of land or hoisted on pillars over the ocean.

If this sounds absurd, take a look at the Arecibo Observatory in Puerto Rico (pictured below), which is home to the world’s largest curved focusing dish.

At 1,000 feet in diameter and situated atop an old sinkhole, the dish is made of aluminum panels and supported by mesh steel cables. Tropical vegetation flourishes underneath, with orchids and lizards inhabiting the ecosystem.

The SPS-ALPHA receptors would be simultaneously powerful, with one in, say, the Mojave Desert easily supplying power for all of Southern California.

In space, the satellites would be able to reach any receptor within its field of view, with as little as four satellites covering the world’s entire surface (though each would only be able to communicate with one receptor at a time).

“A single satellite in orbit above the Indian Ocean can send power anywhere in Africa, Central or Eastern Europe, anywhere in Russia up to Moscow, the Middle East, India and half of China,” Mankins said.

Though he sees it being "immediately market ready" for remote locations.

Making Money Now

While it may take years for the dream to reach fruition – if it ever does – and even longer for something like this to be competitive with the power grid, Mankins sees an ability to profit from SPS technologies in the near term.

Partnering with major communications providers, the technology could be installed on traditional satellites, allowing them to attain a greater source of power at a cheaper cost. It could help boost the satellite’s bandwidth while reducing operational costs, making satellites more profitable and helping to lower excessive launch costs.

“You don’t have to wait until you have solar power satellites to make a lot of money from this,” Mankins said.

High launch costs remain one of this SPS-ALPHA’s biggest roadblocks, and while Mankins says new advances from the likes of Elon Musk’s SpaceX are helping to bring costs down for major providers, he argues further innovation is needed to make space travel -- and satellites -- economically feasible for the little guys.