Democrats, GOP Reps Demand IRS Return Money to Small Businesses

A bipartisan group of Congressmen on the House Ways and Means Oversight Subcommittee sent a letter to Treasury Secretary Jack Lew demanding the government return money to small businesses that the IRS had wrongfully seized under federal asset forfeiture laws.

“As the Treasury Secretary, you have the opportunity to right the wrong done to these small business owners,” the Congressional letter writers said, adding, “You have the discretion to return the seized funds to their rightful owners.”

It’s a rare move made by the Congressmen to circumvent the IRS, which they say has been devastating small businesses with its “abusive” seizures of bank accounts the agency thinks are being used for, say, drug transactions or money laundering.

Under federal forfeiture laws, the IRS has grabbed millions of dollars from thousands of small business bank accounts without first getting proof of criminal wrongdoing. The letter, signed by Republican Congressmen Peter J. Roskam, chair of the subcommittee, and Democrats Charles Rangel and John Lewis, was also sent to U.S. Attorney General Loretta Lynch and IRS commissioner John Koskinen.

The agency argues the small businessmen’s accounts were illegally “structured,” meaning, deposits were made or withdrawn in amounts under $10,000 so as to fly under the radar of government reporting laws banks must abide by.

The reporting requirement stems from a law launched in 1970, the Bank Secrecy Act. The law was intended to target drug dealers, tax evaders, money launderers, and illegal gamblers, among other criminal enterprises. Structuring violations are a felony punishable by a fine and/or up to five years in prison.

But the IRS has been accused of impoverishing and bankrupting small business owners by seizing their assets merely based on suspicion, without any proof of a crime, and often without notice.

Bank accounts are “seized—without due process—simply because of how they [taxpayers] were depositing money,” the Congressmen said in their letter. In some cases, the IRS seized and held bank accounts for years without bringing charges.

The IRS has since apologized for the abuse and said it had altered its regulations late last year to stop seizures based on suspicions of structuring unless the funds came from an illegal source or there were other, exceptional circumstances. “The Department of Justice has since said that it will no longer pursue such cases unless it has reason to believe the deposits are somehow related to underlying criminal activity,” the House lawmakers note.

However, “the IRS and the Department of Justice attorneys who pursued these cases would then offer to settle if the small business owners would agree to relinquish a portion of the seized funds—even though in many of these cases, the DOJ and IRS conceded that the small business owners had done nothing wrong,” the Congressmen said, adding, “The IRS’s October 2014 policy change is tantamount to an admission that it never should have seized funds that were not associated with an illegal source.”

The Institute for Justice, a Washington-based public interest law firm that is seeking to reform civil forfeiture practices, has said: “The IRS practice of ‘seize first, question later’ highlights the need for broad reform to federal civil forfeiture laws that impose substantial burdens on property owners and make seizing property—and profiting from it—too easy for law enforcement.”

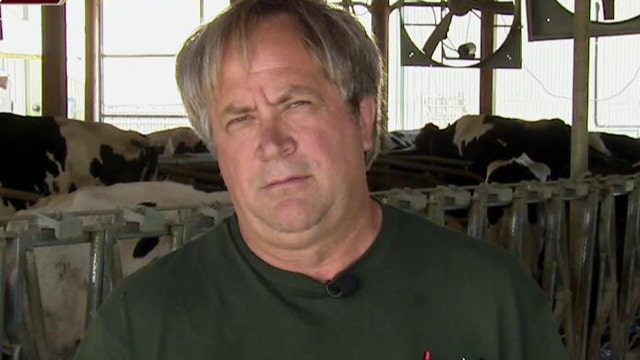

“Some small businesses are still reeling from the seizures,” the Congressional letter writers say. They include Randy and Karen Sowers of Maryland, dairy farmers who operated a farmers market stand who eventually settled with the government for $29,500 after their $67,000 account was seized. “Treasury still holds funds seized from innocent small business owners who settled their cases only because they could not afford to do otherwise,” the Congressmen wrote.

Karen Sowers, according to the Congressmen, was evidently told by a local bank teller to make her deposits under $10,000 so as to reduce paperwork for the bank. After a local reporter published an article on the Sowers’ fight with the IRS, a government “attorney prosecuting the case then stated in an e-mail that the terms of the settlement agreement were harsher than in other, similar cases because Mr. Sowers had exercised his First Amendment right and spoken to the press,” the Congressional letter writers said.

Another entrepreneur, Carol Hinder of Iowa, lost her Mexican restaurant, which she ran as a cash-only business, after the IRS seized her bank account for $33,000.

Oversight Subcommittee chairman Roskam said it took Hinder a year and a half to get her money back. The IRS must “return assets to all taxpayers whose bank accounts were seized inconsistent with the updated policy,” the Congressmen wrote in their letter.

"The IRS grabbed these taxpayers by their throat and squeezed and squeezed and squeezed without mercy and nearly ruined them and made their lives miserable," Roskam said to IRS commissioner Koskinen at a hearing earlier this year. "Would you be willing to apologize to those taxpayers who were so abused?

However, it took a few more demands from chairman Roskam before the IRS commissioner finally admitted he's "sorry that mistakes happen,” adding, "anyone not engaged in illegal activity who got stuck in the system I think deserves an apology. I would apologize to anyone who was not treated fairly under the code."

Small businesses risk bankruptcy, just by fighting the IRS to get their own money back. The median amount seized by the IRS was $34,000, according to the Institute for Justice, while legal costs can easily surmount to $20,000.

The IRS, just like other law enforcement agencies, gets to keep a share of whatever is forfeited. Critics say these kinds of incentives has led to the creation of a law enforcement dragnet in the federal government, with more than 100 multiagency task forces at various agencies combing through bank reports, looking for accounts to seize, according to estimates.

The Institute for Justice analyzed case data from the IRS, and found it conducted 639 seizures in 2012, up from 114 in 2005. Only one in five was prosecuted as a criminal structuring case, it says. Specifically, its analysis shows:

• From 2005 to 2012, the IRS seized more than $242 million for suspected structuring violations in more than 2,500 cases, and annual seizures increased fivefold over those eight years.

• At least a third of those cases arose from nothing more than a series of cash transactions under $10,000, with no other criminal activity alleged.

• Four out of five IRS structuring-related forfeitures were civil, not criminal, so the IRS faced a lower evidentiary standard and did not need to secure a conviction to forfeit the cash, and owners had fewer rights in fighting to win it back. Owners likely face a long legal battle to win their money back: The average IRS structuring-related forfeiture took nearly a year to complete.

• Nearly half of the money seized by the IRS was not forfeited, raising concerns that the IRS seized more than it could later justify.