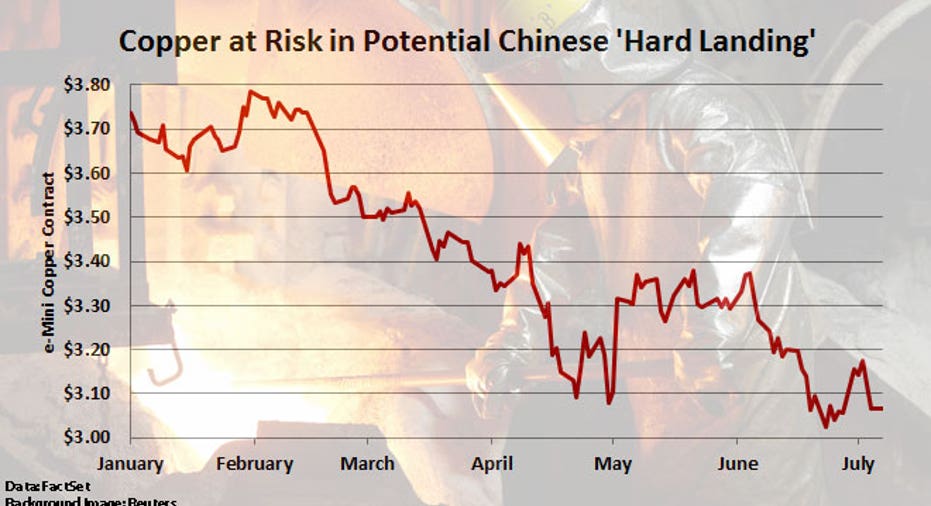

Fears of Chinese Hard Landing Cast a Shadow Over Commodities Complex

Renewed jitters about China’s decelerating economy have raised questions about what happens to prices of metals and energy if the world’s most voracious consumer of commodities suddenly goes on a barebones diet.

Some economists are warning the recent liquidity squeeze that gripped Chinese lenders coupled with the new leadership’s aversion to stimulus raise the risk of a so-called “hard landing” that could briefly send the country’s gross domestic product growth tumbling to as low as 3%.

Such a dramatic slowdown for the globe’s No. 2 economy could spark steep selloffs in the commodities complex, sending copper spiraling 60% and crude oil retreating to $70 a barrel, Barclays (NYSE:BCS) warned in a recent note to clients.

“Fears of a hard landing in China have now become one of the biggest concerns facing commodity markets,” Barclays said.

The credit crunch that spooked global markets late last month has allowed worries about the health of China’s credit-fueled economy to reemerge.

Easy-Credit Withdrawal?

While Barclays is not calling for a hard landing in China and still sees GDP growth of 7.4% in 2013 and 2014, the investment bank now warns that a period where GDP growth plummets to 3% “at some point in the next three years is an increasingly likely scenario.”

This dimmer view on China has been triggered in part by tighter liquidity conditions as Beijing struggles to cool off a credit market that has exploded to $23 trillion from just $9 trillion in 2008. The liquidity squeeze helped spark a 5.3% nosedive for the Shanghai Composite in one day last month, roughly the equivalent of an 800-point meltdown for the Dow Industrials.

In the past, China’s leaders would have simply loosened credit conditions and added more fuel to the country’s economic and credit fire.

However, the new administration has moved in the opposite direction by beginning to remove the easy-money punch bowl, force banks to deleverage and push for structural reform.

All of that is likely good for China’s long-term health, but it’s not exactly a bullish signal in the short term.

It also comes as China’s economy has already been slowing with growth in industrial activity, which accounts for 40% of the country’s GDP, decelerating to just 9% from 20% in 2010.

On Tuesday, the International Monetary Fund warned of a potentially prolonged slowdown in emerging markets and downgraded its projected 2014 Chinese GDP target to 7.7% from 8.3%.

Copper Could Crumble

In terms of financial impact, a hard landing would be hardest felt in the world’s metals market as China’s economic boom has helped prop up global demand for building materials like copper and aluminum.

Barclays modeled a hard-landing scenario by assuming a “rather extreme” 4% year-over-year decline in Chinese aluminum and copper demand, which would be the country’s first annual decline in metals demand since 1988.

Because China has less of a metals inventory overhang than it did before the financial crisis, the analysts believe the downside for these metals is “more limited” than in 2008.

"Slowing growth in the world’s second-largest economy is sending shudders through global markets, and understandably so."

Still, such a reduction in metals appetite would send the aluminum surplus to 3.5 million tons from under 1 million tons now and boost the global refined copper market surplus to 1 million tons from just 100,000 tons now, Barclays said.

In response, Barclays predicted copper, which has the greatest exposure to China and the most room to fall to the downside, could drop 60% from current prices to $2,553 a ton.

Lead and zinc would face sharp declines of 40% to 50% to about $850 and $1,000 a ton, respectively, analysts said.

However, aluminum, which like nickel and zinc is already stuck in a bear market, would probably suffer a more modest drop if China can’t avoid a hard landing, falling about 30% to $1,234 a ton, Barclays said.

Energy Ripple Effects

On the energy front, a severe slowdown in China would have a meaningful impact on oil prices as the country accounts for a whopping 11% of global demand.

Barclays said a hard-landing would likely trigger a 2.5% drop in China’s oil demand, which would be just its second quarterly contraction in the past five years. Including the impact of de-stocking, China’s oil demand could fall 4% to 5%, causing a 500,000 barrel drop in China’s daily crude imports.

The softer demand from the world’s No. 2 economy would likely send crude sinking to around $70 a barrel, Barclays predicted, representing roughly a 30% drop from current levels. By comparison, crude suffered a scarier selloff to just $36 a barrel in the aftermath of the ’08 crisis.

Still, such a decline for crude would likely prompt a quick response from OPEC to curtail production, limiting the impact of the Chinese slowdown.

Soft Landing Hopes Persist

While much of the commodities complex would head south in the event of a Chinese hard landing, one closely-watched and slumping metal could receive a boost: gold.

The precious metal, which has fallen 31% since nearly touching $1,800 an ounce in October, would likely benefit from a structural change in China’s gold demand.

“A hard landing could shake faith in the government” and spark a “big fall” in assets denominated in China’s yuan, Barclays said.

Of course, some observers seem far less concerned about the threat of a steep slump in China.

Last week, J.P. Morgan Chase (NYSE:JPM) told clients to “overweight” exposure to commodities for the first time since 2010.

While acknowledging that “downside returns risk remains high,” J.P. Morgan said it believes “prices have fallen far enough for long enough to force involuntary cuts in production and spur fresh demand.”

Likewise, Helen Qiao, chief greater China economist at Morgan Stanley (NYSE:MS), told clients that although hard-landing concerns are “sending shudders through global markets,” China’s growth likely “stabilized at low levels” in the second quarter, reducing fears that the slowdown would “derail the demand recovery.”