Man who inherits Nat Turner's Bible feels burden of history

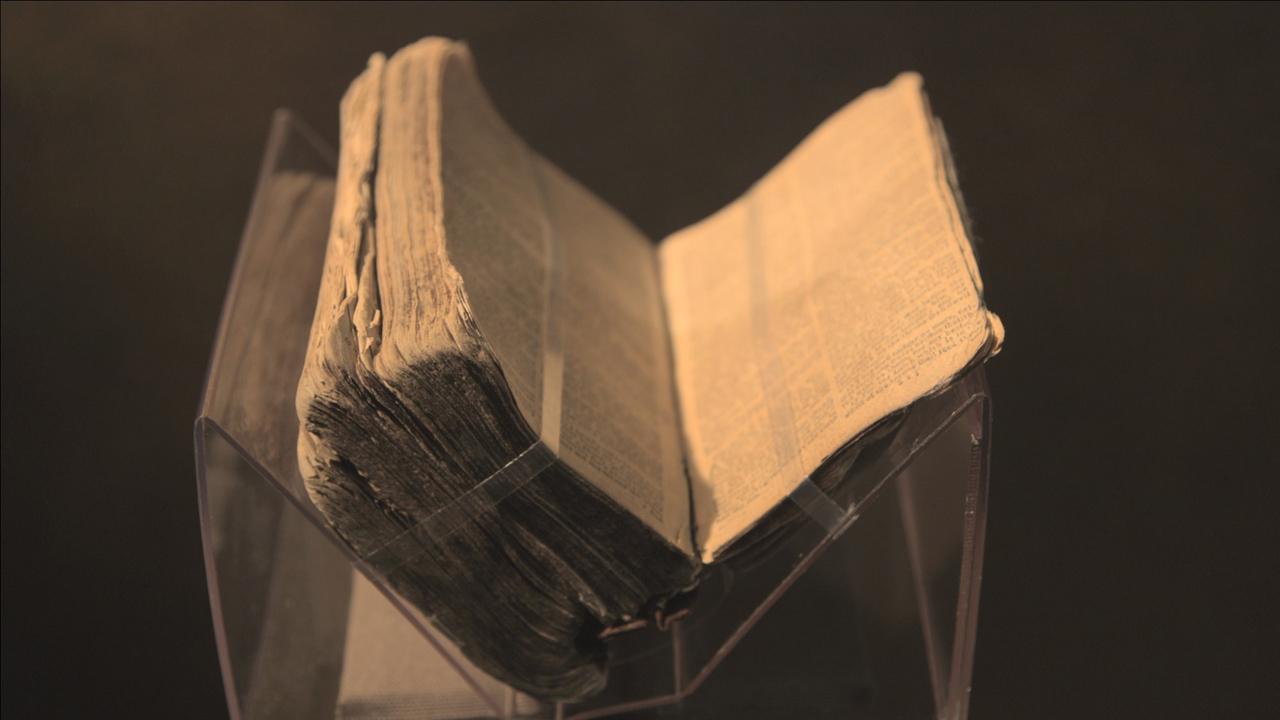

It was a historic relic said to be worth millions – the Bible confiscated from Nat Turner in 1831 after he led the deadliest slave revolt ever in the U.S. But when Maurice Person inherited the book, he felt impelled to hide it away.

“I just don’t think he knew what to do with it,” says Maurice’s stepdaughter Wendy Creekmore-Porter. “It sat in the back of a closet in the dark, wrapped in a cotton towel.”

“You’d ask Maurice a question and he might change the subject or just didn’t elaborate,” adds Mark Person, Maurice’s cousin.

But the Person family does recount their complicated, century-long relationship with the tattered artifact in the season premiere of Strange Inheritance with Jamie Colby. “Nat Turner’s Bible” is the second of two new episodes airing on the Fox Business Network on Monday, Jan. 15 from 9 p.m. to 10 p.m. ET.

Turner, a slave preacher, and his rebel band killed more than 50 white men, women and children—including several of the direct ancestors of Maurice Person.

“Maurice’s pregnant great-grandmother was home alone when a slave next door got word what was happening and warned everybody,” says Creekmore-Porter.

That slave and others hid the helpless woman in a cubbyhole under blankets.

“If it wasn’t for the kindness of these wonderful people, who could have easily have given her up, we wouldn’t be here to tell the story,” Creekmore-Porter says.

At his trial, Turner made clear he didn’t feel that he was guilty of any wrongdong, says historian Kenneth Greenberg.

“He believed he was chosen by God—and the Bible is the key to his certainty,” Greenberg says.

Turner’s copy of the book was submitted as evidence in his trial. He was convicted and hanged, but his name remained on the tongues of Americans in the decades before the Civil War.

It was 47 years after the war, in 1912, when Southampton County court workers, cleaning out the old evidence files, found the Bible and called Maurice’s father, Walter.

“They knew the family’s connection to the slave revolt,” says Creekmore-Porter. “They asked, ‘would you like the Bible that Nat Turner left behind?’”

That was in the middle of the Jim Crow era. Walter Person placed the Bible on the piano in his living room. It remained prominently displayed for 30 years, until he died in 1945.

But when his son Maurice inherited it, he tucked it away.

Creekmore-Porter recalls family members whispering about the Bible in the closet.

“I have always heard, since I was a little child, this Bible was on Nat Turner when he was captured,” she says.

As Maurice grew old and infirm, he finally decided he must deal with his strange inheritance.

“It was always on his mind,” his stepdaughter says.

Though the family was told collectors would pay millions for the Bible, Maurice was unwilling to profit in any way from slavery.

“It belongs to history. It belongs to the world,” he told Creekmore-Porter.

She accepted the task of finding the book a new home.

“I wanted Maurice to be able to not worry about it anymore,” she says.

When she offered the Bible to the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, Associate Director Rex Ellis didn’t know what to think.

“I must admit, my first reaction was ‘Is this a crank call?’” Ellis tells Colby in the program.

But it turned out to be a career find for the curator.

“It is so important. This Bible indicates the faith and the hope that one day slaves would be free,” he says.

The Smithsonian made the Bible a centerpiece of its African American History and Culture Museum, which pleases Nat Turner’s descendant Bruce Turner.

“That Bible is now where it belongs. It’s very important for people to understand that some of the principles that he stood for, equality, freedom, those are the same principles regardless of what your nationality or ethnicity is,” he says.

Creekmore-Porter agrees.

“I’d always said since I was a little girl, this Bible belongs in the Smithsonian. We see this Bible as an act of reconciliation, from our family. I am so honored to help it live on.”