The Fed cuts interest rates for the first time since the financial recession

The Federal Reserve cut interest rates on Wednesday for the first time since the start of the financial recession more than a decade ago, hoping to preserve the 11-year economic expansion from growing global uncertainties and the possibility of an impending slowdown.

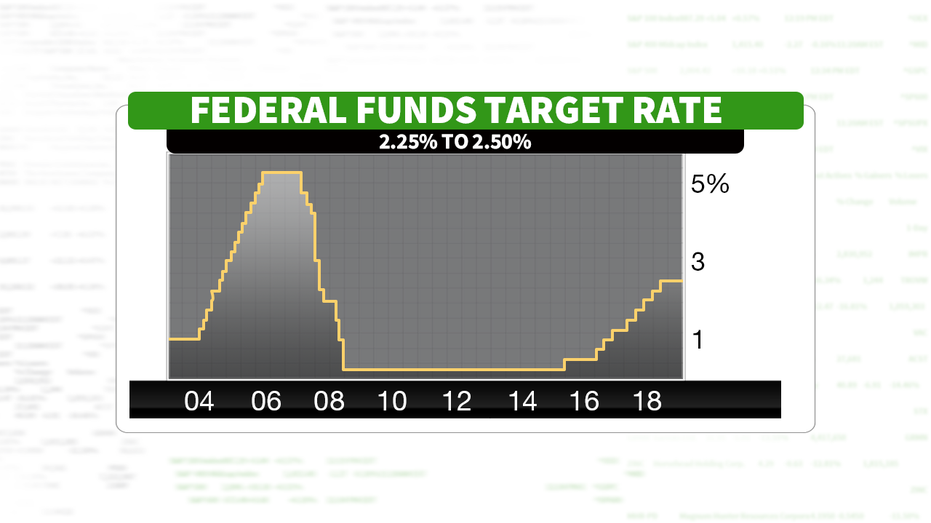

During its two-day meeting, the Federal Open Market Committee voted, as expected, to ease the benchmark federal funds rate by 25 basis points, ending an era of monetary policy tightening by policymakers, who have voted nine times — as recently as December — since 2015 to hike rates.

In approving the cut — the range is now between 2 percent and 2.25 percent — the U.S. central bank cited "the implications of global developments in the economic outlook as well as muted inflation pressures." Those uncertainties include Brexit, the U.S.-China trade war and softening global growth. Policymakers said they will continue to act "as appropriate" to sustain the economic expansion in weighing a potential future cut. Currently, traders are pricing in a 77 percent chance of a second quarter-percent cut during the FOMC's September meeting.

Eight of 10 officials voted in favor of lowering rates, with Boston Fed President Eric Rosengren and Kansas City Fed President Esther George dissenting from the decision.

"We see today's action as more of an insurance ease, even though it is significant," said Tony Bedikian, managing director at Citizens Bank. "Recent economic data has been positive and, while the market had priced in this rate cut and the Fed had telegraphed it, the economy has continued to add jobs and consumer confidence has remained high despite signs of slowing growth and some market uncertainty.”

The cut will likely placate President Trump, who frequently belittles the Fed, and its chairman, Jerome Powell, for raising interest rates too high, too quickly — but also raised questions about whether the U.S. central bank is truly independent, given the stronger-than-expected economic data out of the U.S. in the past few months. For instance, in the spring, the U.S. economy expanded at a 2.1 percent annualized rate, beating Wall Street's expectations.

"The issue is more the downside risks and the shortfall in inflation," Powell said during a press conference. "We’re trying to address those. In addition, going forward, I would say, we’ree going to be monitoring those same things, the evolution of trade uncertainty, of global growth and of low inflation. We’ll also, of course, be watching the performance of the U.S. economy...We’ll be putting all of those together, and that’s how we’ll be thinking of policy going forward."

It is a fairly remarkable policy shift for what is typically viewed as a slow-moving regulatory body, reversing years of slow-but-steady tightening. The Fed has not reduced interest rates since 2008, when it essentially dropped rates to zero to cope with the fallout from the financial crisis. At the time, the GDP was at -0.1 percent, and unemployment was at 6 percent.

Experts caution, however, that concerns over a slowing economy are warranted, are not necessarily evidence of the Fed caving to external pressure from the White House.

"A variety of signals suggest the economy’s long recovery from the Great Recession has slowed in 2019," said Adam Ozimek, Upwork's chief economist.

For consumers, lower interest rates — which affect borrowing costs, including auto loan rates and 30-year-fixed mortgage rates — can mean thousands of dollars in savings, spurring spending. Although the lending rate is the highest level in years, it's low by historical standards. But Fed officials believed it was better to cut rates now to prevent a recession than to wait for an economic slowdown.