Worry and relief at EPA after scandal-plagued chief's exit

WASHINGTON – Taking over from an ambitious predecessor known for seeking out the rich, powerful and conservative, the Environmental Protection Agency's newly named acting chief has promised to reach out to anxious staffers throughout the demoralized agency and to lawmakers of both political parties.

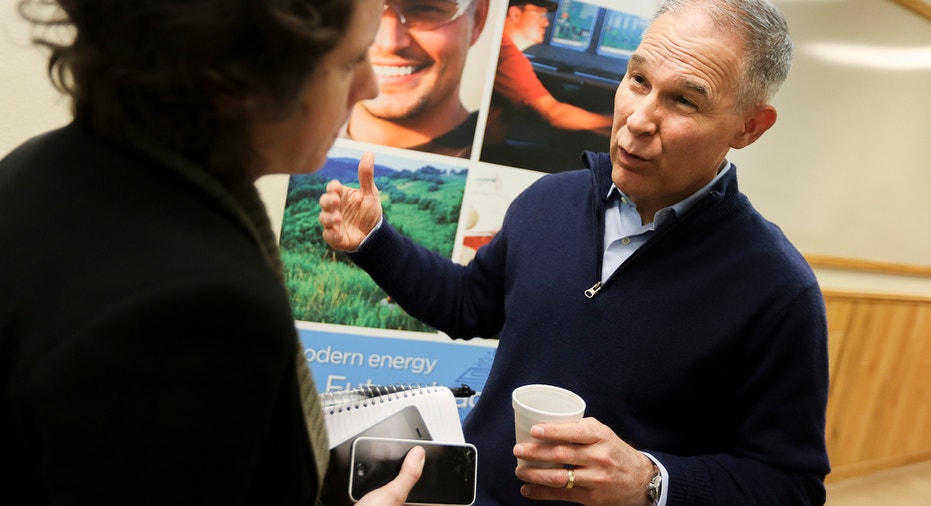

By late afternoon Friday, there had been no public comment from either Scott Pruitt, whose resignation President Donald Trump announced Thursday after months of Pruitt's ethics scandals, or Andrew Wheeler, the Washington veteran and former coal lobbyist who Trump announced as the agency's acting head.

In an email sent out to EPA staffers Thursday night and obtained by the Associated Press, Wheeler said he was honored to take temporary leadership of the agency where he started his Washington career in the early 1990s, as an EPA employee dealing with toxic substances and other matters. "I look forward to working hard alongside all of you," Wheeler wrote agency employees.

Pruitt, Oklahoma's attorney general at the time of his EPA appointment, had embraced the perks of office in Washington. He instituted unusual and costly round-the-clock protection for himself, flew premium class to Europe and North Africa, and directed agency staffers to help seek housing for his family, high-dollar employment for his wife, and pleasures such as luxury lotion and tickets to top sporting events.

Trump had praised Pruitt for his regulation-trimming ways at EPA. On Thursday, however, Trump said Pruitt himself had concluded the EPA chief's ethics scandals were too much of a distraction and was stepping down.

Some EPA staffers linked to Pruitt's tumultuous 17-month tenure feared for their jobs Friday, former top staffers under Pruitt said. That included the roughly 20 members of a security detail Pruitt's EPA had created to guard him around the clock.

The guards were originally trained for investigating environmental crimes. The agency's security officials are expected to decide what level of protection Wheeler needs.

"There's definitely that fear" of a shake-up among Pruitt's remaining political appointees, said Kevin Chmielewski, the former deputy chief of staff who fell out of favor with Pruitt after questioning spending. "This is the follow-up stories, the people's lives he's affected, going down to the agents and everyone else."

Some scientists and other career staffers, who learned of Pruitt's departure through news and social media on Thursday, quietly expressed relief, Elizabeth Southerland, who quit last year as the science director at the agency's Office of Water, said after hearing Thursday and Friday from many still at the agency.

Wheeler's public statements show him to be a skeptic, like Pruitt, about the extent to which coal, oil and gas emissions drive climate change, something that mainstream science says is indisputable fact.

After leaving his four-year stint at the EPA in the 1990s, Wheeler became the top staffer for the Senate's most ardent challenger of manmade climate-change, Republican Sen. James Inhofe of Oklahoma. Wheeler then went to work as a lobbyist for top coal companies and other businesses and interests.

In a hearing on his appointment as the agency's deputy administrator last November, Wheeler described himself as someone who "always tried to find common ground and work across the aisle" in Washington.

Where Pruitt openly criticized the work of EPA employees under the Obama administration, Wheeler at the Senate committee hearing made a point of praising the agency's career staffers as "some of the most dedicated and hard-working employees" in federal government.

Wheeler told the Washington Examiner earlier this year he was focusing on repairing relationships with EPA career staff who bristled at Pruitt's leadership.

At the EPA, staffers expect Wheeler to stick to the agenda set by Pruitt and Trump: Cutting environmental regulations that the Trump administration and industries see as unnecessarily burdensome to business, Southerland, the former water official, said.

"There's not a single person who doesn't think that will happen," Southerland said of the current EPA staffers she has talked to.

However, "they think at least the contemptuous behavior will stop," she said. She was referring to allegations that Pruitt ignored all but his own political appointees at the agency, and used his office for personal gain.

EPA's press office sent out biographical information on Wheeler late Friday, but did not respond to interview requests for him.