Stock market's coronavirus plunge conjures 1987 crash flashbacks

'We just don't know how long a time this shock is going to last'

Get all the latest news on coronavirus and more delivered daily to your inbox. Sign up here.

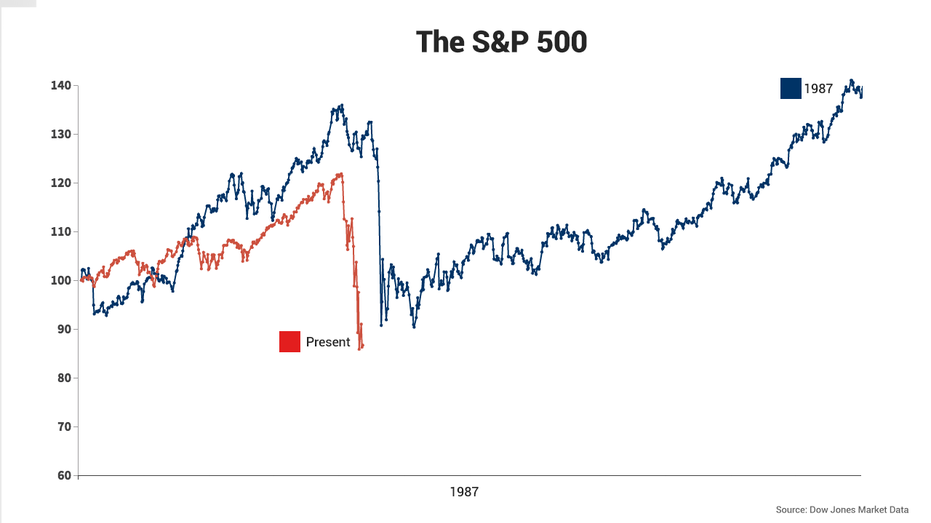

The stock market's coronavirus-driven plunge is suffused with shades of Black Monday, the October 1987 crash that still lives in infamy on Wall Street.

The S&P 500 index plummeted 22.6 percent on that day near the end of the Reagan era, the largest drop in its history, spurring comparisons with the start of the Great Depression.

To many who lived through it in the trading pits of Chicago and on trading desks on Wall Street, the index’s current 34 percent plunge over the last 23 trading days has striking similarities.

“This whole period, this panic that everybody has reached, it just seems and feels like the ‘87 crash,” Blair Hull, the market maker at the Chicago Board of Trade who bought the 150 major market index futures that traded at the absolute low in 1987, told FOX Business.

DESPITE CORONAVIRUS, NEW BULL MARKET CAN RUN

His friend, Anthony Saliba, who traded options at the Chicago Board Options Exchange during the 1987 crash, agreed.

“I feel a lot of that right now,” said Saliba, who pointed to the “unprecedented” and “sustained” volatility in equities today.

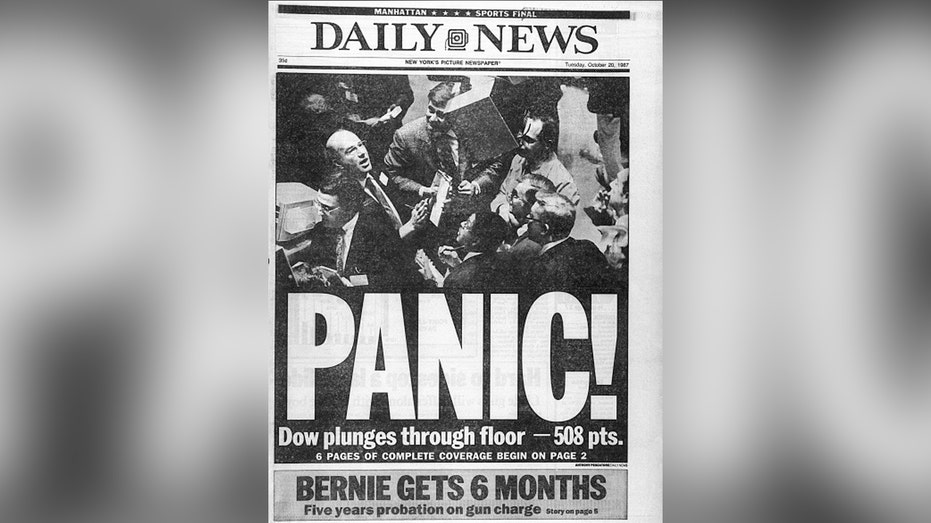

The front page of the New York Daily News during the 1987 stock market crash. Tuesday Oct. 20, 1987. (Getty)

The CBOE S&P 100 Volatility Index, or VXO, a measure of stock-market volatility, closed at a record high 150.19 on Oct. 19, 1987, the day remembered as Black Monday. Aside from a handful of days following the crash, the VXO’s next three highest closes, 93.85, 89.8 and 89.61, occurred during the current market plunge, according to the Dow Jones Market Data Group.

This panic that everybody has reached, it just seems and feels like the ‘87 crash.

Despite the similarities between the two events, there are significant differences, said David Rosenberg, whose first day working on Wall Street as a junior economist at Bank of Nova Scotia was Black Monday.

While both events were marked by a “precipitous plunge,” the 1987 crash was caused by the structure of the market and the rapid proliferation of portfolio insurance that “ended up exacerbating the liquidity strains,” Rosenberg, now chief economist and strategist at Toronto-based Rosenberg Research, told FOX Business.

He added that then-new Federal Reserve Chairman Alan Greenspan had been “dramatically raising interest rates into the summer of 1987, draining liquidity and flattening the yield curve.”

Even when the market crashed, the economy grew at 5 percent and unemployment stayed at its low of the cycle – unlike the present. Now, economists are predicting a 10-fold increase in the number of people filing for unemployment along with a drop of 20 percent or more in gross domestic product.

In response to the economic fallout from COVID-19, the Federal Reserve slashed interest rates to zero, announced programs to ensure financial markets were functioning correctly and said it would buy unlimited assets to support the economy.

CORONAVIRUS WILL US ECONOMY HARDER THAN 2008 FINANCIAL CRISIS: JPMORGAN

Congress has also taken action, passing two laws and working on a third that would deploy $1.4 trillion to give cash to individuals, small businesses and corporations hit hardest by the virus.

“Today, we have the underlying problem that we just don't know how long a time this shock is going to last,” said Torsten Slok, chief economist at Deutsche Bank.

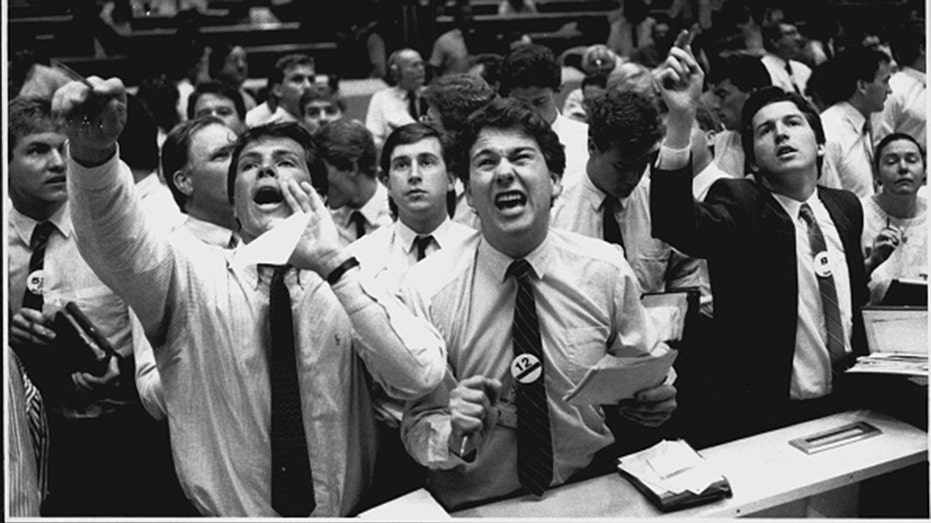

Stock market crash, October 1987. (Photo by Antonin Cermak/Fairfax Media via Getty Images).

Slok believes the stock market will remain volatile until we see a “flattening out of the virus curves,” which could still take weeks. The number of people infected in the U.S. increased by nearly 500 percent over the past week to almost 46,500, according to the latest data from Johns Hopkins University & Medicine.

“In 1987, there was a very limited impact from markets to the economy, whereas today, the weakening economy is the No. 1 reason why markets have been doing so poorly,” Slok said.

He added that the rebound will likely be “more muted” this time around as hardest-hit consumers and companies exercise caution as they try and rebuild their savings.

As for the markets, Rosenberg says bottoming after a bear phase is a “process” and “not a point in time,” adding that investors are hardly penalized for missing the first year of a bull market. On average, those who sat out the first year of the bull-run garnered a return of 14 percent on an annualized basis. Those who didn’t saw an annual return of 16 percent.

CLICK HERE TO READ MORE ON FOX BUSINESS

As for Saliba, now CEO of the Chicago-based Matrix Execution Group, an executing broker-dealer that specializes in options and equities, he believes the sharp drop that occurred in downside volatility on Monday suggests “the water is safe” and the stock market isn’t going a lot lower.

Hull, now chairman of the Chicago-based Hull Tactical Funds, said last Wednesday, when the stock market was halted seconds into trading, felt “an awful lot like the '87 bottom,” when he made his memorable trade.

“This too shall pass,” he said.