Opponents sue to nix ballot measure to split California in 3

SACRAMENTO, Calif. – Opponents of an initiative to split California into three states asked the state Supreme Court to pull the measure from the ballot, arguing it's too drastic a change to state government to go through the normal initiative process.

A lawsuit filed Monday by the Planning and Conservation League argues major changes to the state's government structure require approval from two-thirds of the Legislature before going under consideration by voters or a state constitutional convention.

The initiative would break the state into Northern California, California and Southern California.

Northern California would comprise the Bay Area, Silicon Valley, Sacramento and counties north of the current state capital. California would be a strip of land along the coast stretching from Los Angeles to Monterey. Southern California would include Fresno and the surrounding farming communities, reaching all the way to San Diego and the Mexican border.

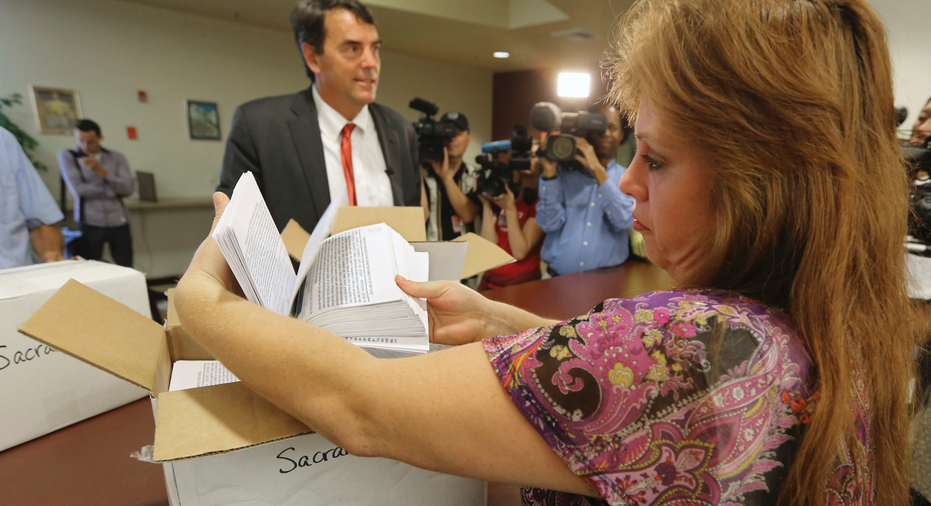

Venture capitalist Tim Draper is financing the "Cal 3" initiative in his latest attempt to divide the state. He has spent more than $1.7 million supporting it. The nation's most populous state has become too difficult to govern because of its size, wealth disparities and geographic diversity, Draper and the initiative's supporters argue.

Draper did not comment on the lawsuit because he had not seen it. A spokeswoman for the initiative also did not comment.

The California Supreme Court has tossed initiatives in the past after ruling they went too far in changing government structure.

For example, in 1990 the court got rid of part of a measure to reform the state's criminal justice system after voters passed it because the court found it revised the state Constitution beyond what could be done through an initiative.

In another case in 2000, the court struck a measure on lawmaker compensation and redistricting from the ballot before it went to voters because the justices found it violated the state's single subject rule, which requires that initiatives deal with just one issue.

Draper's measure is an abuse of the ballot initiative system, said Carlyle Hall, a lawyer working on the lawsuit.

"The dislocation and the disruption that would be caused by something as great as this just can't be understated," he said. "This will not make things better."

Michael Salerno, a law professor at UC Hastings, described the change that the initiative is trying to make as profound.

"It would not surprise me if the court took this off the ballot," he said.

Loyola law professor Jessica Levinson said it makes sense for opponents to argue that the initiative substantially revises the state's governing structure, but she added that judges are often reluctant to pull measures from the ballot.

The initiative could harm the environment if California's strong environmental protections are scrapped and replaced with something weaker, which could happen if the state were split, Hall said.

Draper's last attempt to divide the state in six didn't gather enough signatures to make the ballot in 2016.

Although California as it exists today is heavily Democratic, the newly proposed Southern California might not be. Democrats have only a slim registration advantage over Republicans in that region.