Judge slashes $50M punitive penalty against pork giant

RALEIGH, N.C. – A federal judge has slashed $50 million in damages that a jury awarded neighbors of an industrial hog operation in order to punish a pork producer for smells and noise so bad that people couldn't enjoy their rural homes.

U.S. District Judge W. Earl Britt ruled this week that North Carolina law required him to cut the size of punitive damages to $2.5 million total for the 10 plaintiffs. Attorneys for the homeowners did not respond Wednesday to requests for comment.

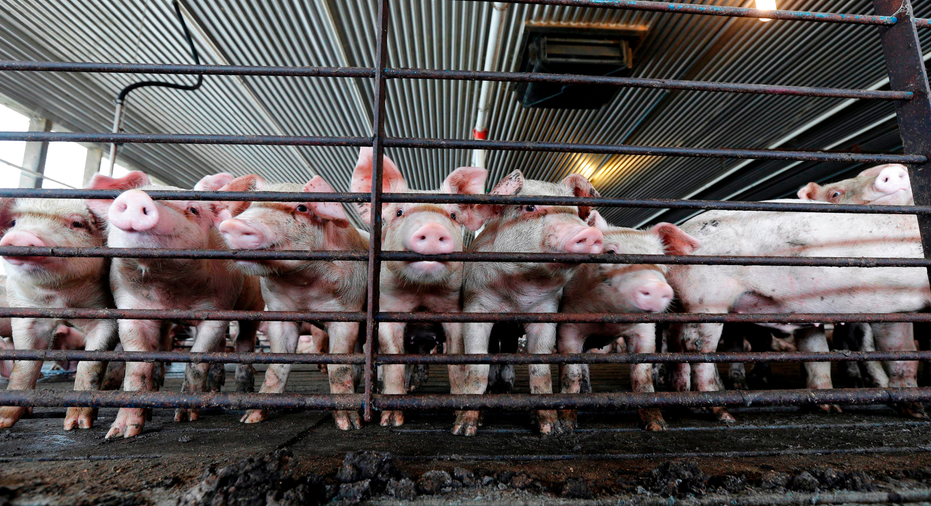

Britt cited state law that limits the punishment for corporate misdeeds to no more than $250,000, an amount 1/20th the $5 million that jurors last month ordered Smithfield Foods to pay each neighbor. Neighbors of a 15,000-head Bladen County swine operation also were awarded $75,000 each in compensation for conditions that prevented them from enjoying their own property.

Plaintiffs' attorneys had argued the state's cap on punitive damages was unconstitutional because it violates the right to a jury trial. However, attorneys for the neighbors recognized they were asking Britt to rule contrary to a 2004 state Supreme Court decision that determined that limiting how heavily misdeeds could be punished was no barrier to a jury deciding who was at fault.

"The jury's role in awarding punitive damages can be dictated by our state's policy-making body, the General Assembly, without violating plaintiffs' constitutional right to trial by jury," Britt wrote in his order filed Monday.

The decision was the first in dozens of lawsuits filed by more than 500 neighbors complaining about hog operations.

North Carolina legislators last year changed state law to make it much more difficult to replicate such nuisance lawsuits targeting hog operations.

Smithfield Foods called the lawsuits "a serious threat" to its North Carolina livestock operations and related jobs. The company has said it would appeal last month's jury decision.

Lawyers targeted the hog-production division of Virginia-based Smithfield Foods — not the Bladen County farm's owner — because they said the Chinese-owned company uses strict contracts to dictate how farm operators raise livestock that Smithfield owns.

The judge's order is unlikely to affect the upcoming negligence lawsuits targeting North Carolina hog operations because jurors aren't told their award could be capped, Wake Forest University law professor Sidney Shapiro said. That's because if jurors knew the law limited damages that are meant as punishment, they might inflate how much they award in compensation.

Shapiro thinks Britt's order might be appealed since it doesn't address that the Smithfield Foods neighbors complained about nuisances that show no signs of stopping as long as industrial-scale hog operations keep their current method of waste handling.

"The plaintiffs argued that the punitive damages were necessary as a deterrent," he said, "that it was necessary for the jury to indicate to the defendants that their wanton behavior, if continued, would continue to endanger the plaintiffs' property. That's the argument that the judge didn't deal with one way or the other."

Rural residents have complained about smells, clouds of flies and excessive spraying for decades. But local and state politicians have either supported the politically powerful industry or backed down in the face of its clout.

Smithfield Foods hasn't changed the locally dominant method of hog waste disposal since intensive hog operations multiplied in North Carolina in the 1980s and '90s. The practice involves housing thousands of hogs together, flushing their waste into holding pits, allowing bacteria to break down the material, then spraying the effluent onto fields with agricultural spray guns.

Neighbors say the spraying sends the smells and animal waste airborne, allowing it to drift into their homes and sometimes coat outdoor surfaces on their properties.

___

Follow Emery P. Dalesio on Twitter at http://twitter.com/emerydalesio . His work can be found at https://apnews.com/search/emery%20dalesio