Inside the World of Micro-Cap Investing

Ian Cassel is a full-time privatemicro-cap investor and the founder of MicroCapClub.com.The 35-year-old lives in Lancaster, Pennsylvania. Motley Fool analyst Rana Pritanjali recently interviewed Cassel about why he invests in micro caps and how he unearths the best investments the sector has to offer. Read on for Cassel's insights.

Rana Pritanjali: What made you choose micro caps as your hunting ground?

Ian Cassel:Micro caps (less than $300 million market capitalization)are even smaller than small caps, but I think they provide an excellent opportunity for investors. The goal is to find great companies early that are run by intelligent fanatics. You only need to find one great company every few years to beat the market and to change your life.

I started investing when I was a teenager and first started digging into micro-cap companies in college. One of the first micro-cap companies I researched was XM Satellite Radio (which later merged with Sirius) in 2002. XM Satellite Radio was my first micro-cap investment and also my first experience meeting management. This is when my love affair with micro-cap stocks began. I was completely drawn to the fact that a "nobody" like me had the ability to access management and gain an edge. Long story short, over the next several years I would hone my craft and become a full-time private micro-cap investor in late 2008.

The overall pitch for micro-cap investing is somewhat simple: Micro-cap companies represent 48% of all public companies in North America. The approximately 11,000 micro-cap companies in North America have a combined market value of $490 billion, about the current market capitalization of Googleparent company Alphabet (NASDAQ: GOOG). Some of the best investors ever, including Warren Buffett, Peter Lynch, Joel Greenblatt, and many others started their careers investing in micro caps. Some of the best-performing public companies ever, including Berkshire Hathaway (NYSE: BRK-B), Wal-Mart (NYSE: WMT), Amgen (NASDAQ: AMGN), Netflix (NASDAQ: NFLX), and many others started as small micro-cap companies. The key to outsized returns is finding great companies early because all great companies started as small companies.

The last several months have been challenging for micro-cap investors ... however, investors should view this as an opportunity. Valuations have come down, and competition for new ideas is decreasing. If history has shown us anything, it's that bad market environments are the best time to find great opportunities.

Rana Pritanjali: Is the success rate lower in micro caps? And how and when do you decide that your investment thesis is busted?

Ian Cassel: I think your success rate is a function of your experience level. Warren Buffett says, "Risk comes from not knowing what you're doing." I certainly didn't know what I was doing in my early investing career. My investment philosophy was molded and shaped over years of learning by losing my own money over and over again. I've never played baseball, so I wouldn't expect to be able to hit a pitch thrown by a professional pitcher. But given enough time and experience, I would slowly develop the ability to wait and swing at the right pitch. The market throws pitches at us every day. Over time, you figure out your strike zone or your circle of competence and you wait for your pitch.

If you know what you are doing, I think you can have a good success rate, but you will never be right nine times out of 10. And you don't have to be. In the micro-cap space, if you find a great company early, you can make 10 or 20 or 50-plus times your money over the long term. One winner can make up for all your losers.

The key to successful investing is letting your winners run and cutting your losers as soon as possible. "The Most Important Thing" in micro-cap investing is to know your positions better than most. This is the only way to form the conviction to hold multi-baggers and also gain an edge in selling before the masses. Micro-cap companies are illiquid. When you know your positions better than most, you can spot signs of your investment thesis cracking long before others. There is no formula for this as it's very much a gut-feel type of thing. It is hard to have formulaic selling rules like, "After three earnings periods of underperformance, I will sell." You need to pick up on clues (local news, industry reports, scuttlebutt, etc.) before it's obvious to everyone. It is the difference between getting out with a profit versus a big loss. Normally when I stop wanting to buy more and start rationalizing my investment, it is a sign to sell.

Rana Pritanjali: I think averaging up is still a slightly new concept for traditional value investors. Is averaging up a more popular concept than averaging down for smaller companies?

Ian Cassel:Successful investing is hard work because it means disciplining your mind to do the opposite of human nature. Human nature drives us to do financially stupid things like selling our winners to buy more of our losers. I would say the concept of averaging up isn't very popular anywhere because it's counter to human nature. The concept really hit home for me when I analyzed my winning positions over the years. All my winners had one thing in common. I was always averaging up. I'm a firm believer in only owning your highest-conviction positions, and oftentimes you already own your best investment opportunities. As a company executes and your conviction grows, own more of it. Don't have a mental block against owning more of what you own. Let the management and company execution decide your position sizing.

Rana Pritanjali:What kind of margin of safety do you prefer for micro caps?

Ian Cassel:I want to invest in undervalued companies that can get overvalued. When you buy your initial position, you want to find situations where you believe you are buying the business well below intrinsic value. In general, you want to wait for fat pitches where if your investment thesis is completely wrong, you will still make money. That said, I'm not a deep value investor. I don't want to own something that is undervalued that will always be undervalued. I want to own businesses that can become great businesses. Great businesses always get overvalued because there is a scarcity of great businesses in the marketplace.

Rana Pritanjali:How big a role does management play in your investment thesis? Do you personallytalk to management before making an investment decision? How do you evaluate management?

Ian Cassel:Evaluating and interviewing management is a big part of what I do. Betting on the right jockey is equal to or more important than betting on the right horse. The smaller the company, the more influence founders and management have over its direction. Founder-CEOs oftentimes wear a lot of hats at micro-cap companies, intimately influencing every aspect of the business. You need to make sure you are betting on the right jockey.

I believe in Phil Fisher's approach to business analysis. After exhaustive quantitative due diligence, scuttlebutt research, and talking to those that have differential insights, the final hurdle is talking to management. By the time you talk to management, you want to be more than halfway toward a buying decision. You use management interviews/discussion to fill in any holes or questions you have about the business or strategy. After a couple phone conversations, I then set up a time to visit the company at its headquarters. Nothing can replace meeting management face to face. The qualitative nuggets of information about their leadership and the business are invaluable. Conducting site visits and talking to line workers and employees (many of whom have worked for competitors) is very useful.

Microcap companies are generally small, young, emerging companies with short operating histories. Many of these companies' founders are new entrepreneurs, so you don't have much history on which to judge. The management's previous corporate experience and track record might not be helpful, either. Running a division of a large company is much different than running a small business on a tight budget. I'm looking to identify good businesses that can become great businesses that are run by intelligent fanatics. Many investors mistake an executive with charisma for being an intelligent fanatic. The thing we learn from books like The Outsiders by William Thorndike is that many of these great CEOs/capital allocators weren't charismatic. They were iconoclasts that let their execution do the talking. This is what I look for in micro caps. The only way to really evaluate these managers is watching their decision-making and execution over time. This is another reason why I believe in averaging up. Let management prove themselves before you buy more.

Rana Pritanjali:Do you believe in holding forever, or do you exit a position as soon as the valuation doesn't make sense anymore?

Ian Cassel:The principle of holding forever is good in theory, but it's likely not realistic for micro-cap investing. I believe in holding a position as long as the story doesn't change and management executes. If you are doing it right, the positions you've held the longest should be up the most. I believe in constantly evaluating my current investments against new opportunities. As a full-time investor, I need to sell an existing position to buy a new position. You want to always be positioned in the best companies you can find. When you put in the work (quantitative-qualitative analysis) to know your positions better than most, a new opportunity can't just be slightly better than an existing position, it needs to be substantially better.

In general, these are my four reasons to sell a position:

- Sell when you find something better.I'm a full-time private investor. I don't manage a fund. I don't have capital inflows where I constantly have new money to put to work. I have to sell a position in order to buy a new position. When you find a company that is significantly better than what you already own, own it.

- Sell when the story changes.When you see the first cracks in your investment thesis, you sell. You need to know your positions better than most so you are the first to see the cracks.

- Sell at the first sign of managerial incompetence or unethical behavior.There are times when you see management make such a bad decision that you need to sell. You will know it when you see it. Just like cockroaches, when you see one dumb decision, you know it won't be long until you see more. Life is too short to be invested in management teams you don't respect.

- Sell when the company gets very overvalued.If a management team is executing, I'm a big fan of holding. I have no problem holding companies through the peaks and troughs of the market, but there are times when the valuation gets way too far ahead of itself. I like to gauge quarterly performance and stock performance of my positions against my three- to five-year estimates. When expectation and reality get too far out of whack, it's good to take some off the table.

Rana Pritanjali:Are micro caps more challenging to understand? Do you take a venture-capitalist approach to micro caps?

Ian Cassel: Micro caps are illiquid and their business prospects can change very quickly, so it's imperative you continue to do maintenance analysis on your positions. However, I believe micro caps are less complex and easier to understand than larger companies. Can you really understand General Electric (NYSE: GE), Johnson & Johnson (NYSE: JNJ), or any other mega cap? I know I can't. Micro caps and small caps are the best of both worlds because they are smaller, often simpler, businesses that few look at. Institutions can't buy micro caps until they are larger and more liquid. Coincidentally, this why you see liquidity increase as the stocks go up. As an experienced investor, micro-cap investing is a game you can win.

Micro-cap investing and venture-capital investing are similar in that it's a bet on founders; however, venture capital is normally chasing unprofitable technology/life-science companies. In the micro-cap space, you can find growing, profitable businesses with good prospects trading at a fraction of VC valuations.

Rana Pritanjali:What are some of the key things you consider when you evaluate a micro-cap company?

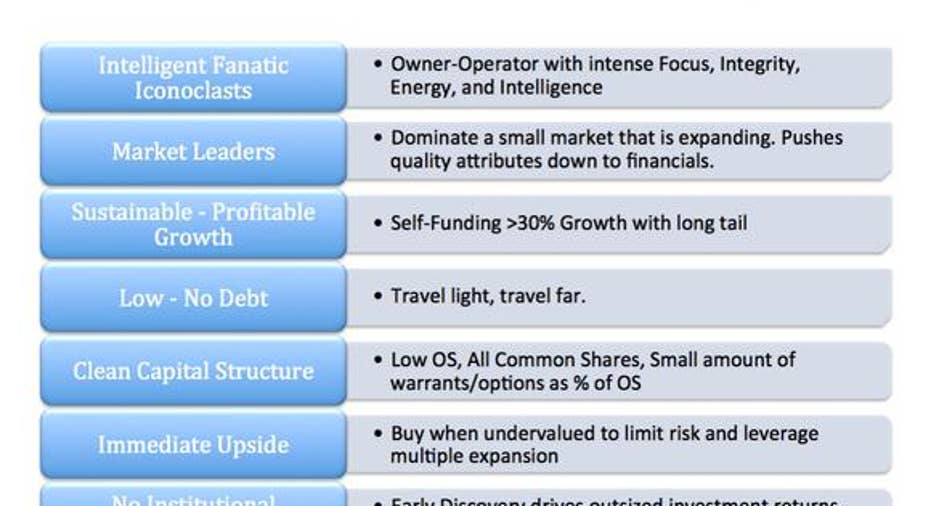

Ian Cassel: In 2015, I studied the best-performing stocks over the last five years. Almost all of these companies were small micro-cap companies that turned into small caps. On the list were about 120 companies that were up 1,000% over the past five years. The top 10 companies were companies that were up anywhere from 8,000% to 67,000% in five years. There were eight 100-plus baggers that occurred in a five-year time period on U.S./Canadian exchanges. Those percentages and timeframes aren't typos. The companies on this list are the companies I want to find early. When I analyzed these companies as well as multi-baggers I've invested in, there were characteristics and similarities among them. In the illustration below,I highlight these characteristics.

- Intelligent Fanatic Iconoclasts: The combination of all these traits below multiplied by execution is what makes an intelligent fanatic. You can oftentimes find these intelligent fanatics early by looking for iconoclasm.Intelligent Fanatic = (Long-Term Vision + Focus + Energy + Integrity + Intelligence) x Execution

- Market Leaders: For a small micro-cap company to be a market leader, it must dominate a small market. Peter Thiel wrote about this in Zero to One. I want to own businesses that dominate a small market that is expanding. This normally pushes quality attributes down to the financials.

- Sustainable, Profitable Growth: Find growing profitable companies that can sustain their growth for the foreseeable future. My biggest risk as a micro-cap investor is dilution. I want to find companies that are self-funding compounding machines.

- Low to No Debt: I've found that small micro-cap companies and debt don't go well together. Debt can really strangle a small company, and with micro-caps, it usually comes in the form of high-interest dilutive convertible debt.

- Clean Capital Structure: You can learn a lot about the management team by the share-capital structure. I look for low outstanding shares, all common shares, and a low amount of warrants/options as a percentage of outstanding shares. You want to invest in managers that treat their shares like gold.

- No Institutional Ownership: When you find and invest in great businesses that bigger money doesn't own yet, the stock has nowhere to go but up.

- Immediate Upside: Buy when the business is fundamentally undervalued to limit risk and to fully leverage multiple expansion. Your margin of safety is buying an undervalued business that can get overvalued.

The article Inside the World of Micro-Cap Investing originally appeared on Fool.com.

Suzanne Frey, an executive at Alphabet, is a member of The Motley Fool's board of directors. Rana Pritanjali owns shares of Johnson & Johnson. The Motley Fool owns shares of and recommends Alphabet (C shares), Berkshire Hathaway, and Netflix. The Motley Fool owns shares of General Electric Company. The Motley Fool recommends Johnson & Johnson. Try any of our Foolish newsletter services free for 30 days. We Fools may not all hold the same opinions, but we all believe that considering a diverse range of insights makes us better investors. The Motley Fool has a disclosure policy.

Copyright 1995 - 2016 The Motley Fool, LLC. All rights reserved. The Motley Fool has a disclosure policy.