Employers jump into providing care as health costs rise

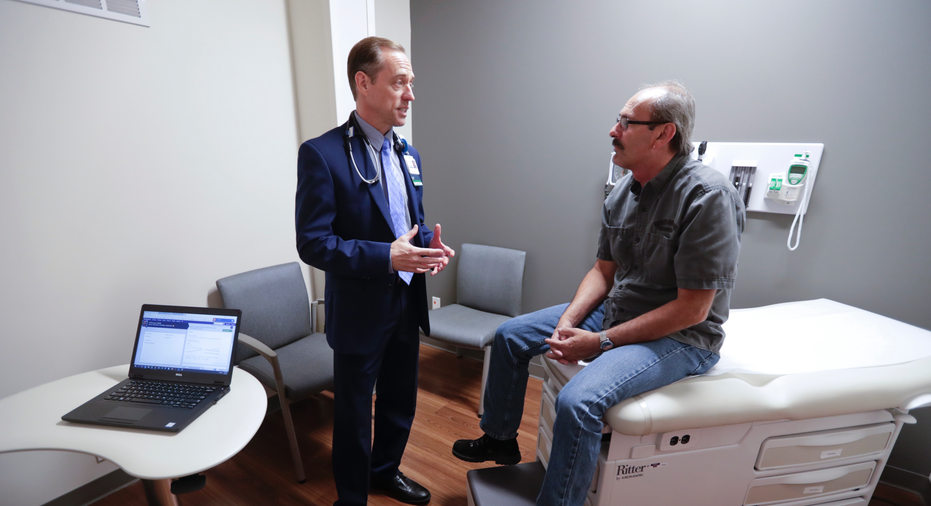

Dr. John Lynch meets with patient Jeff Thieke during his visit to the Fiat Chrysler Automotive Clinic in Anderson, Ind., Tuesday, Sept. 4, 2018. Fiat Chrysler is offering free care for its employees and their families, about 22,000 people, through a clinic the carmaker opened this summer near one of five factories it operates in the area. (AP Photo/Michael Conroy)

KOKOMO, Indiana – Autoworkers in this blue-collar, central Indiana city have an eager helper waiting to pick up the bill at their next doctor visit.

Fiat Chrysler is offering free health care for most of its employees and their families — about 22,000 people — through a clinic the carmaker opened this summer near one of five factories it operates in the area. The company pays for basic care like doctor visits and consults with a dietitian and even an exercise physiologist. Workers don't pay a cent, not even a co-pay.

The idea: Spend more now to improve care and eventually pare the more than $100 million that Fiat Chrysler Automobiles pays annually for health care, just in Indiana.

"We looked at how do we change the health care delivery system, that's really what employers are asking," Fiat Chrysler executive Kathleen Neal said.

Corporate America is jumping deeper into the care its workers receive beyond just giving them insurance cards and a list of doctors they can visit. Companies are opening clinics on or near their worksites or bringing in temporary setups to make sure their employees get annual physicals.

In many cases employers are offering free primary care or charging only a small fee. Many believe the cost is worthwhile because they can improve employee health and cut even bigger bills in the future that stem from unmanaged chronic conditions like diabetes or unnecessary emergency room visits.

Offering convenient care can also help attract new workers and cut down on time away from the job. But this shift means workers will have to change how they use the health care system. And companies, which don't see individual medical records, have to patiently wait for some potential benefits from their investment like a drop in health care costs.

"It is really, really hard to change behavior," said Carolyn Engelhard, an associate professor at the University of Virginia's medical school who studies health policy.

Big companies have long offered services to help employees recover from workplace injuries, and now more are delving into primary care.

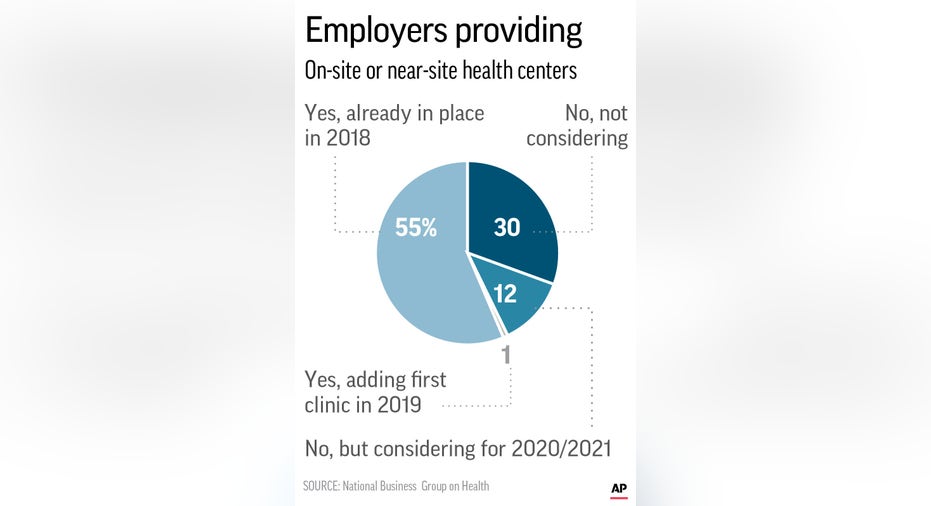

Fifty-six percent of large employers will have on-site or nearby health centers by 2019, up from 47 percent in 2016, according to the National Business Group on Health.

Most of the businesses surveyed by the nonprofit, which represents large companies, have 10,000 employees or more. But benefits experts also see this trend in smaller businesses too, with some companies joining forces to pay for a nearby clinic that they share.

Office buildings also have started adding clinics to attract tenants that want the convenience for their employees, according to Dr. Jeff Dobro, a partner with the benefits consultant Mercer.

Mattress maker Serta Simmons Bedding started rolling out mobile health clinics to all 28 of its U.S. factories a couple years ago to help its largely male workforce get annual physicals, with the company covering the cost.

"Most people just don't get their screenings, and a lot of men just don't have a relationship" with their doctor, said company executive Steven Wilkinson.

Fiat Chrysler opened its clinic after learning that 40 percent of its employees in the Kokomo area didn't have a primary care doctor, and many defaulted to emergency rooms for care that wasn't dire.

Company spokeswoman Val Oehmke declined to say how much the clinic cost to build, but she said Fiat Chrysler expects to make back what it spent in about two years by improving employee health and cutting medical costs.

The health center comes with exam rooms, an X-ray machine and space for minor procedures. Aside from a small memorial photo of former Fiat Chrysler CEO Sergio Marchionne on a waiting room table, few signs inside the clinic connect it to the hulking transmission factory nearby.

The carmaker pays a local hospital operator, St. Vincent, to run its clinic exclusively for employees and family members.

Dr. John Lynch spent almost an hour with a patient during a recent physical. That compares to the 10 or 15 minutes he used to get once or twice a year in other practices.

"It was frustrating that I couldn't do more for them," he said.

Forklift operator Amanda Chipps took her toddler, McCoy, to the clinic after he developed a fever and a rash and she couldn't get in to see their regular doctor. Chipps said that visit felt more like an annual checkup. Before eventually prescribing antibiotics, a doctor and nurse asked about McCoy's medical history, diet and personality.

"They were really just getting to know ... everything about him," she said. "It was just real nice, a different setting from most doctors' offices."

United Shore Financial Services opened a similar clinic in its suburban Detroit headquarters for its 2,600 employees a couple years ago after executives saw workers coming in sick during flu season. The clinic logged about 4,200 visits in 2017, its first full year.

Account executive Sean McHugh said he seeks clinic help when back trouble flares up during the day. That saves him from losing time by driving home for care and then back to work.

"It really makes the work environment here appealing because it gives you your time outside of the office," the 36-year-old said.

Employers often find that it takes time for workers to get used to a major change in health benefits.

But these clinics can catch on quickly, said David Keyt, a Mercer executive who works with employers to set them up. He said having clinics on or near the worksite removes two big hurdles — cost and convenience— that prevent people from getting care.

"What we're trying to get to is the provider-patient relationship and all the barriers that prevent that ... from happening," he said.

___

Follow Tom Murphy on Twitter: https://twitter.com/thpmurphy

___

The Associated Press Health & Science Department receives support from the Howard Hughes Medical Institute's Department of Science Education. The AP is solely responsible for all content.