Debt-Limit Deal Is Done, U.S. Averts Default

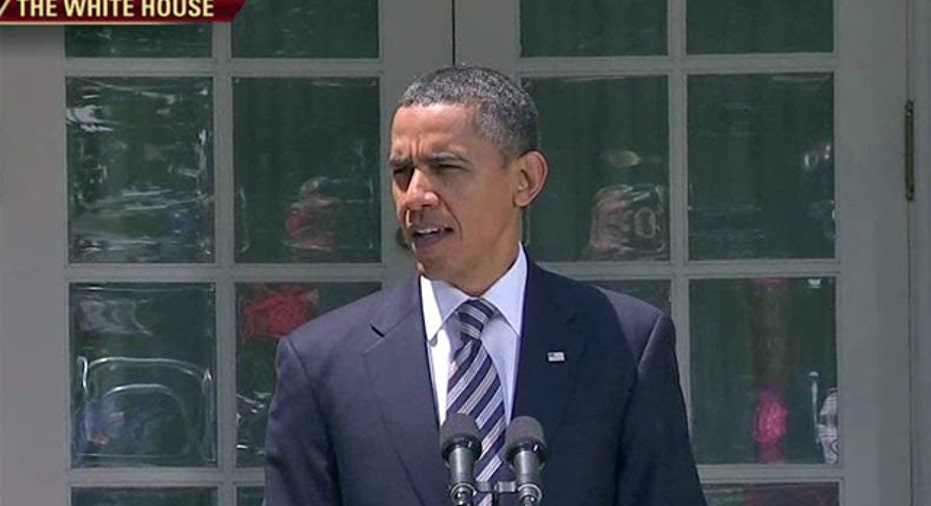

An agreement to raise the U.S. debt limit by $2.4 trillion sailed through the Senate on Tuesday and was quickly signed by President Obama, averting a long-threatened government default by a few hours.

The vote in the Senate was 74-26 in favor, after the House passed it by a 269-161 margin last night.

Congressional approval of the deal, which also seeks to trim more than $2 trillion in spending over the next decade, marked the end of a months-long game of political chicken in which both parties sought to redefine the way government pays for the services it promises to provide.

It was a heated and prolonged battle even by Washingtons exaggerated standards.

Still, passage of the agreement is no guarantee the U.S. will retain its coveted AAA credit rating. The three big ratings firms Standard & Poors, Moodys Investment Services and Fitch have all threatened to lower the U.S. ratings if Congress fails to adequately rein in the deficit. S&P has targeted $4 trillion in cuts as a starting point.

The firms have said they need to review the debt agreement further before deciding whether to move ahead with a downgrade or take it off the table. Fitch said Tuesday a decision could come by the end of the month.

For decades, Congress has raised the debt ceiling almost annually with little controversy or public debate. But this year was markedly different as the U.S. has struggled to recover from the worst financial crisis since the Great Depression. Government spending and ever-widening budget deficits -- and the taxes needed to fill those deficits -- have emerged as top priorities for many voters, and Washington has taken notice ahead of the 2012 presidential election.

The Treasury Department had warned for months that the debt limit needed to be raised above its $14.3 trillion limit. Republicans and Democrats insisted that any agreement to raise the debt limit be tied to measures to reduce the gaping U.S. budget deficit. How best to do that kept both sides at odds as an Aug. 2 deadline approached for when the Treasury claimed the U.S. would run out of money to pay some of its bills.

A default by the U.S. on its debt was widely viewed as potentially devastating to the global economy. At best, it would have been deeply embarrassing to the U.S.

As with most big congressional compromises, hardly anyone was completely satisfied. Fiscal conservatives, in particular those aligned with the tea party movement, said the spending cuts werent deep enough. Liberal Democrats said the cuts unfairly targeted important social programs that benefit the poor and the elderly.

Also, Democrats had sought spending cuts offset by mandated tax increases, mostly on wealthier Americans. Many Republicans, meanwhile, had sought a constitutional amendment that would have required Congress to pass a balanced budget each year, something 49 of the 50 states requires.

The agreement, reached Sunday night, calls for an incremental increase of the debt limit by $2.4 trillion in three phases. Specific spending cuts of $917 billion over 10 years are included in the deal, while $1.5 trillion in additional cuts will have to hashed out in the future by an as-yet appointed Congressional committee.

That latter point has drawn criticism because it allows the politicians to postpone hard decisions on funding for such popular programs such as Medicaid and Medicare so-called entitlement programs which all but guarantees more bickering and dithering when the time comes to make those cuts.

Spending for health care-related programs in particular will have to be addressed as millions of baby boomers approach retirement age and the costs for those entitlements are expected to rise accordingly.

Both sides agreed well ahead of the compromise reached Sunday that no one wanted a default. Some economists had said a default by the U.S. on its debt obligations could set off a ripple effect whose ramifications could potentially be more severe than the recent financial crisis. Others argued the U.S. could juggle its debts to minimize the impact of temporarily running out of cash.

Nevertheless, one proposal after another was rejected as the Aug. 2 deadline approached. Republicans accused Democrats of being chronic spendthrifts, and Democrats said Republicans want to cut programs for the most vulnerable.

Media attention on the arguing grew intense in recent days, and polls showed a vast majority of Americans strongly disapproved of Congress seeming inability to get something done.

Now its done -- for the time being anyway.