China's African population declines amid slowdown, crackdown

GUANGZHOU, China – Dreams are fading in China for African traders like Mouhamadou Moustapha Dieng, who in 2003 was among the first wave of Africans to set up homes and companies in this port city and forge trading links between China and the African continent.

Young African traders who want to follow in the footsteps of Dieng's generation complain of difficulties getting visas, police crackdowns and prejudice, which come amid rising nationalism and slowing economic growth. Guangzhou is believed to have the largest African population in Asia, but many are leaving as long-time traders struggle against a slowdown in the Chinese economy and increased competition from Chinese traders and the internet.

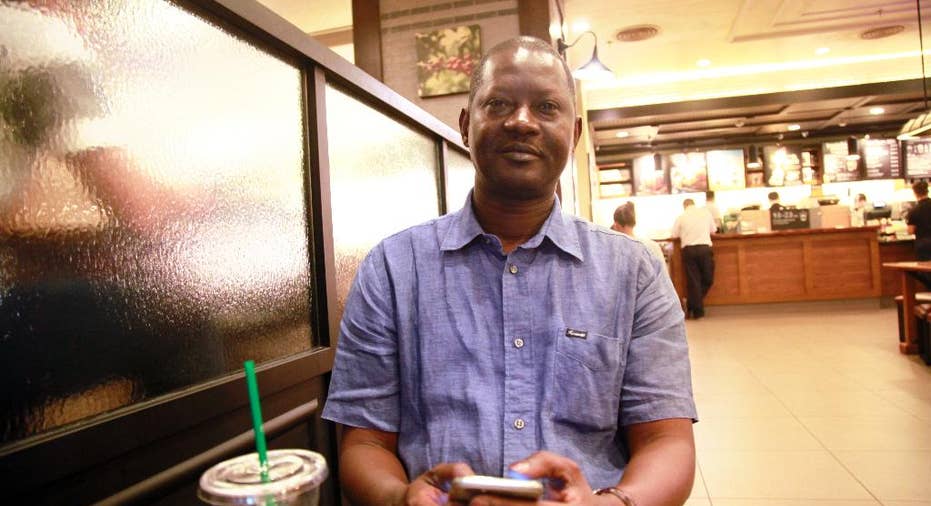

"Now the trade is almost finished," said Dieng, 54 and from Senegal. His profits are down 40 percent from a decade ago. In the absence of a Senegalese consulate in the city, newly arrived 20-somethings on tourist visas head directly to his office for advice on how to do business in China.

"They come with their bags, they sit down, they don't have anywhere to sleep, they don't have money," said the father-of-four. "Most of them, after 10, 15 days they go back."

Over recent decades, Chinese companies and entrepreneurs have spread out across Africa building stadiums, roads and other large projects, cultivating land, running hotels and opening restaurants. Less well-known are the thousands of Africans who live in or regularly visit the southern trading port of Guangzhou, which neighbors Hong Kong. Estimates of this population of residents and floating traders vary, and the police's entry-exit administration declined to comment or offer data. The city's vice mayor said in 2014 that there were approximately 16,000 Africans in Guangzhou, of which 4,000 were residents. Guangzhou's population is 13.5 million.

The first African traders started arriving in Guangzhou in the late 1990s, attracted by its annual international trade fair, China's economic boom and the ease of doing commerce in the city thanks to its wholesale markets, factories and low prices. Guangzhou had benefited from being one of the first Chinese cities allowed to open up to business in the 1980s, giving it a head start in attracting exporters.

Now that rosy picture has faded. Traders have to compete with online companies like Alibaba that allow customers to order from their offices rather than going to markets. They also have more competition from Chinese, like Dieng's former employee who started her own business targeting his clients after picking up the Senegalese language Wolof.

The Associated Press spoke to 15 Africans in Guangzhou, both residents and traders who travel back and forth. Some long-timers reported that the city had become more welcoming over the years as mutual understanding increased between Chinese and Africans. But others spoke of hostility from locals and authorities, which comes amid a growing wariness of foreigners promoted by President Xi Jinping's administration. Observers say the Communist Party is leaning on nationalism to distract from slowing economic growth.

Claudia Thaiya, 30, who sends electronics, furniture, clothes and shoes back home to Kenya, says when she went to look at an apartment recently, the advertised price went up when the landlord saw her. In some shops, she says, she hears derogatory comments about her skin color. "It shows that we're seen as dirty," said Thaiya, a former teacher.

Benjamin Stevens had a business selling liquor in Zambia before coming to study Chinese and civil engineering two years ago. He says he sees Africans being stopped by police to have their papers checked every day, and Chinese move away from him on the subway.

"Now what I plan is to get what I want and that's the knowledge, about civil engineering, and go and put it into practice in my country," he said.

Dieng, who lives close to the center of Xiaobei, an urban village nicknamed "Little Africa," said that for the past year, he has had to register at the local police station every month, rather than annually as in the past.

"It seems they want the Africans to leave this area," Dieng said. "Every month now, I have to go to the police station, every month. I feel like I'm in jail."

An officer at the Jianshe police station, who did not identify himself, said that it "depends on different cases" as to how often foreigners should register.

Heidi Haugen, who researches Africans in China at the University of Oslo, said that the government wants to appear "in control to their local constituents — although they're not elected, that's an all-important part of legitimizing the government."

"So if the immigrant population becomes too large and too visible, then that can become a political problem in itself," she said.

City authorities are attempting to move foreigners out of Xiaobei. For years it has been filled with African traders, along with Middle Eastern and Chinese Muslim shops and restaurants, and is within walking distance of several provincial and city government offices.

Authorities are hoping African businesses will relocate to a development, Guangda Business City, a 40-minute drive away.

"Xiaobei is a very small and crowded downtown area, where so many African residents mingle with local Chinese, so there are some problems, if not conflicts, owing to their different cultures and lifestyles," manager Deng Qiangguo said.

The city government declined to comment.

Africans in Guangzhou organize themselves into unofficial communities according to nationality. These communities, which offer members mutual support, report membership has declined over the past two years. The head of Guangzhou's Tanzania community, John Rwehumbiza, said numbers had gone down "tremendously" this year from about 200.

"Many are going back," said Rwehumbiza. "Number one because of the competition. Number two most of them feel they will do better back home than here."

Chuka Jude Onwualu, of the Nigerian business group Association of Nigerian Representative Offices in China, or Anroc, said they had lost up to a quarter of their members since their peak of 80, and business visas were harder to get.

"If you haven't been to China before there's every likelihood you will be denied a visa, so for new people it's really very difficult," he said.

Dieng, who became a trader in China after a career as a pilot and engineer in the Senegalese army, has sold sports shoes, jeans, T-shirts, electronics and buildings materials during his 13 years here. He employs more than 20 Chinese and a handful of Africans. Now, he's putting his last hopes into shipping, and, if that doesn't work, his plan is to move back to Senegal and open a small factory.

"It's near the end," he says of his time in Guangzhou.