Takeaways from the case of WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange

Julian Assange gestures as he arrives at Westminster Magistrates' Court in London, after the WikiLeaks founder was arrested by officers from the Metropolitan Police and taken into custody Thursday April 11, 2019. Police in London arrested WikiLeaks founder Assange at the Ecuadorean embassy Thursday for failing to surrender to the court in 2012, shortly after the South American nation revoked his asylum .(Victoria Jones/PA via AP)

WASHINGTON – Julian Assange's arrest on Thursday in the Ecuadorian Embassy in London opens the next chapter in the saga of the WikiLeaks founder: an expected extradition fight over a pending criminal prosecution in the United States.

It's also likely to trigger a debate over press freedom and call attention to unresolved questions about Assange's role in the release of stolen Democratic emails leading up to the 2016 presidential election, part of special counsel Robert Mueller's recently concluded investigation into ties between the Trump campaign and Russia.

Some takeaways from Assange's arrest:

THE CHARGES IN THE U.S.

Assange, for now at least, faces a single count of computer intrusion conspiracy.

He's accused of conspiring in 2010 with Chelsea Manning, then a U.S. Army intelligence analyst who leaked troves of classified material to WikiLeaks, to crack a password that would give her higher-level access to classified computer networks.

Prosecutors say Assange and Manning tried to conceal Manning's role as a source by deleting chat logs and removing usernames from sensitive records that were shared. They used a special folder to transmit classified and national defense information, the indictment says. Assange ultimately requested more information related to the password, telling Manning that while he had tried to crack it, he "had no luck so far."

PRESS FREEDOM IMPLICATIONS

Assange and his supporters say he's a journalist who deserves legal protections for publishing stolen material. But the indictment doesn't really have to do with whether Assange is a journalist.

The allegations don't relate to the publication of classified information but focus on his attempts to obtain the material in what prosecutors say was an illegal manner.

That distinction could be vital in the government's case and complicates Assange's efforts to cast the prosecution as infringing on press freedom. Justice Department media guidelines are meant to protect journalists from prosecution for doing their jobs, which has historically included the publication of classified information. But the protections don't easily extend to journalists or others who themselves break the law to obtain information or who solicit others to do so, as the government alleges.

"The act of coaching" someone how to steal information, as alleged in the indictment, "is a step too far," said Ryan Fayhee, a former Justice Department prosecutor who specialized in counterintelligence cases.

Assange may well have grounds to argue that, unlike Manning or government officials or contractors, he had no obligation to safeguard American secrets.

But his publication of stolen Democratic emails during the 2016 campaign and reliance for them on a foreign adversary like Russia may undermine any defense claim that he's motivated by a public good.

"His conduct, and his organization's conduct, I believe, undermines any defense that he would pursue having to do with his genuine interest in rooting out corruption and his absolute commitment to transparency," Fayhee said. "Because Russia is anything but the right model to point to in terms of transparency."

WHAT HAPPENS NEXT

Assange is expected to fight extradition to the U.S., a process that could stretch out for years.

He has a top-notch legal team, many devoted supporters and the legal issues in the U.S. case may prove complex.

Assuming he is eventually brought to the U.S., Assange would face charges in the Eastern District of Virginia, just outside Washington. The office has considerable experience in national security prosecutions involving accused terrorists and spies and other high-profile matters, like the case against former Trump campaign chairman Paul Manafort.

Justice Department officials could easily supplement their indictment with a new one with more serious charges. Manning was jailed last month after she refused to testify before a grand jury in Virginia, suggesting that prosecutors' work related to Assange is not done.

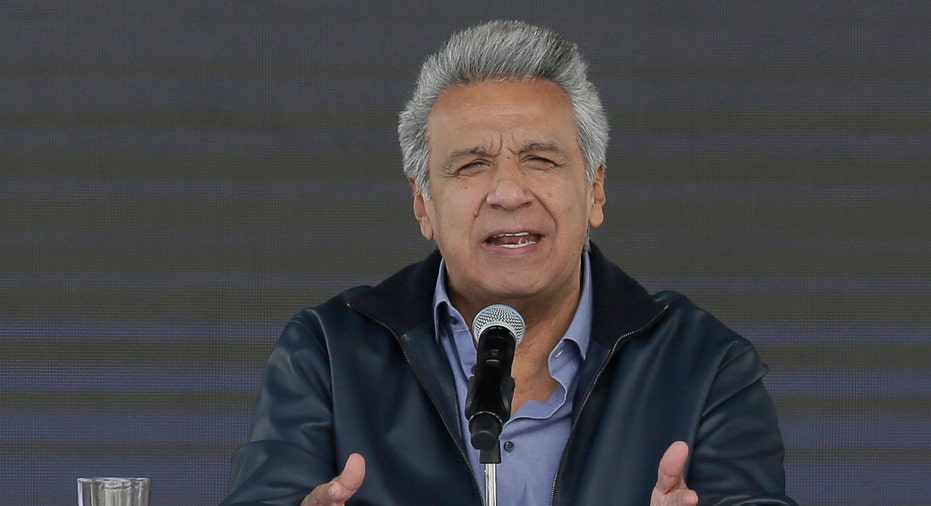

Ecuador's president, Lenin Moreno, said he had secured a guarantee from the United Kingdom that Assange wouldn't be extradited to a country where he could face a death penalty. That's likely a reassurance to Assange's supporters, but the charge he currently faces carries just a five-year maximum penalty.

The Espionage Act can carry the death penalty for people who deliver national defense information to foreign nations, but that charge was not brought against Assange in the current indictment.

Though some of the language in the indictment, including the references to national defense information, mimics the Espionage Act, there's no allegation Assange disclosed American secrets to a foreign power with the goal of harming the U.S.

CONNECTION TO MUELLER'S RUSSIA INVESTIGATION

On its face, the charges have nothing to do with Mueller's probe.

The indictment was brought not by Mueller and his team but rather by prosecutors in Virginia and the Justice Department's national security division.

There is no allegation in the indictment of any involvement in Russian election interference, coordination with Russian hackers or interactions with Trump campaign associates.

That's striking since Assange and WikiLeaks have surfaced, albeit obliquely and not by name, in multiple criminal cases brought by Mueller. WikiLeaks was the organization that published Democratic emails stolen by Russian intelligence officers. And Roger Stone, a Trump confidant under indictment, repeatedly boasted of connections to WikiLeaks and of having advance knowledge of the organization's publication plans.

It is unclear what information, if any, Assange might be willing to offer about how WikiLeaks came to possess the stolen emails.

Mueller has farmed out investigations peripheral to his central mission to other Justice Department offices. Though Assange and WikiLeaks cut to the heart of the question of whether the Trump campaign colluded with Russia, the special counsel ultimately closed his investigation without charging him and before he could even be taken into custody.

That could suggest Mueller didn't see a criminal case to be made against Assange or deferred to the Justice Department's existing investigation into him.

____

Associated Press writer Raphael Satter in London contributed to this report.