Sweden's clean corporate image dealt blow with insider trading case

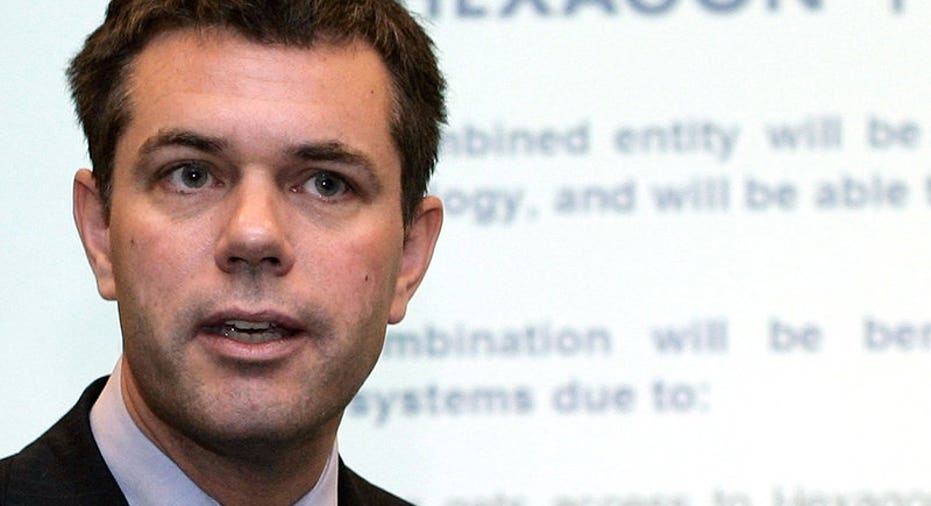

STOCKHOLM – The arrest of Hexagon chief executive Ola Rollen, one of Sweden's most successful CEOs, on suspicion of insider trading could not only threaten the company's standing but also the business reputation of the country.

Sweden has traditionally been seen as one of the world's cleanest, least corrupt nations. It ranks third in Transparency International's corruption perceptions index for 2015.

But the Hexagon affair follows a string of scandals among blue-chip companies involving alleged bribery, offshore tax havens and the misuse of corporate money that have dented that image.

Sweden, said Markus Kallifatides, an associate professor at the Stockholm School of Economics, was not immune to "human greed, stupidity and disloyal behavior".

Rollen was arrested on Oct. 26 by Norwegian authorities for questioning over potential insider trading in Next Biometrics ASA in a deal unrelated to Hexagon. He denies wrongdoing and Norwegian police have not made formal charges.

Norway's public prosecutor said on Thursday police would release him from custody no later than Saturday, but that the investigation into the matter would go on.

Hexagon Chairman Melker Schorling has reiterated his support for Rollen, who was named just this month by Harvard Business Review as one of the world's top 100 best-performing CEOs.

But the affair has sent the technology company's shares tumbling and analysts have expressed concern over the potentially longer-term impact on it.

The 51-year-old protege of prominent businessmen Melker Schorling, Rollen is credited with turning Hexagon from a sprawling conglomerate into one of Sweden's most valuable and celebrated companies.

"Ola Rollen has a really good track record at Hexagon, so it's clear that he, hypothetically, would be hard to replace," said Asa Vasshagen, who is responsible for corporate governance issues at the Swedish Shareholders' Association.

The timing is also a blow for Hexagon as its chairman, Schorling, announced only a week earlier that he would be stepping down due to health issues.

ARE WE BETTER?

Sweden's corporate world was already shaken, with more than a dozen executives from major companies replaced following scandals involving a company controlled by Industrivarden , one of the country's biggest investment groups.

Sweden saw a 14 percent rise in registered economic crimes in 2015 from the previous year, according to the Swedish Economic Crime Authority.

"Are we better? No, I don't think so. There is no difference between how Swedish companies behave versus other countries," said Sasja Beslik, head of sustainable finance at Nordea.

A spending scandal involving the misuse of a corporate jet and lavish hunting parties at hygiene products firm SCA last year prompted change at Industrivarden.

Industrivarden and Wallenberg-backed Investor AB control more than half the Swedish stock exchange.

Nordea , the country's biggest bank, has been fined for serious deficiencies in tackling money laundering and was named more than 10,000 times in the Panama Papers for helping clients set up accounts in offshore tax havens.

Two top executives at Swedbank were allowed to conduct property deals as a side business, sometimes with the bank's customers. The bank chairman and CEO were both ousted when it came to light they had approved of the dealings.

Telecoms operator Telia Company got into hot water for its dealings in Eurasia when bribery allegations resulted in the exit of the company's former CEO and most of the board.

The former CEO of Fingerprint Cards , a competitor of Next Biometrics ASA, has also been accused of insider trading. He has denied any wrongdoing.

Fredrik Erixon, head of Brussels think tank European Centre for International Political Economy, said that Sweden's corporate culture was too insular.

"There are not that many individuals in a decision-making position for nominating board members and deciding on the general corporate governance structure of many firms," Erixon said.

"I would say that if you know 100 people in Sweden, you basically know them all."

The insular culture made it difficult for some leaders to take tough decisions, he said.

About 23 percent of directors in Sweden are on three or more boards, versus the 11 percent EU average, a Heidrick & Struggles survey from 2014 showed.

Another problem is that institutional investors have taken bigger stakes in recent years in Sweden's biggest firms but did not tackle corporate governance issues head-on and did not act like long-term owners, he said.

"No one knows exactly at the end of the day who exactly is responsible," Erixon said.

Institutional investors make up about one quarter of owners in Sweden compared with below 15 percent for the European market, according to a 2015 report from the International Finance Corporation.

Kallifatides said he thought corporate leaders may have grown too far removed from ordinary shareholders, something exacerbated by rising inequality.

This could be contributing to more "unorthodox practices" in both the public and private sector.

"Whenever there is power and money there will also be bad judgment, excessive greed and also power struggles, of course," he said.

(Additional reporting by Olof Swahnberg, Johannes Hellstrom and Johan Ahlander, and Simon Jessop in London, Editing by Alistair Scrutton and Angus MacSwan)