South America's elusive LulzSecPeru hackers embarrass politicians with dumped emails

LIMA, Peru – The Peruvian hackers have broken into military, police, and other sensitive government networks in Argentina, Colombia, Chile, Venezuela and Peru, defacing websites and extracting sensitive data to strut their programming prowess and make political points.

Their latest stunt may be their most consequential.

Emails that the LulzSecPeru hackers stole from the Peruvian Council of Ministers' network and dumped online last month fueled accusations that top Cabinet ministers have acted more like industry lobbyists than public servants. They helped precipitate a no-confidence vote last week that the Cabinet barely survived.

The hackers are a compact, homegrown version of the U.S. and U.K-based LulzSec "black hat" hacker collective that grew out of the Anonymous movement, which has variously attacked the Church of Scientology and agitated on behalf of the WikiLeaks online secret-spillers and Occupy Wall Street.

A lot of "hacktivism" out of the United States and western Europe has waned or been driven underground after police pressure and arrests, said Gabriella Coleman, an anthropologist at McGill University, in Montreal, Canada, who has studied the phenomenon.

"The hackers in Latin America, however, never really stopped," Coleman said.

Of them, LulzSecPeru is widely considered the region's most skillful and accomplished hacktivist team, said Camilo Galdos, a Peruvian digital security expert, their signature exploit hijacking the Twitter accounts of Venezuela's president and ruling socialist party during elections last year.

"Happy Hunting!" the LulzSecPeru hackers — they say they are two young men — wrote last month when they dumped online the estimated 3,500 emails of then-Prime Minister Rene Cornejo, dating from February to July.

Cornejo told reporters: "The concern isn't so much for the information to be found there but for the fact that privacy was violated." His successor, Ana Jara, said some of the purloined emails may have concerned matters of "national defense."

But what reporters found instead was evidence of the inside influence of Peru's fishing and oil industry lobbies, putting the country's energy and finance ministers in the hot seat.

In one missive, a fishing industry executive asks the finance minister if the anchoveta season can be extended. She later gets her wish.

The energy minister, in a testy email exchange, impatiently dismisses objections by the environment minister to his coziness with an Australian oil company with offshore concessions. Oil industry technicians — not regulators — are best qualified to deem whether environmental impact studies are necessary for exploratory seismic testing, he says.

The "CornejoLeaks" spectacle, as the press dubbed it, delighted the hackers.

"We're mixed up in everything," one of the duo, who goes by the nickname Cyber-Rat, boasted in an encrypted online chat with The Associated Press into which he had tunneled, hiding his digital tracks. "There is no limit to the hacking."

Cyber-Rat says he's 17 and will quit before becoming an adult to avoid landing in prison. He handles the social networking, cultivates the Anonymous activists who help publicize LulzSecPeru's hacks and admits to "a tendency toward narcissism." His partner goes by Desh501, says he is between 19 and 23 and a university student.

Desh is the technical whiz, and more reserved.

"I'm very private. I don't have hacker friends in person, only virtually," Desh types.

Both say they are autodidacts. Cyber-Rat says he started programming at age 8; Desh at age 6.

Cyber-Rat says their hacking is not really ideologically driven.

"It's a quest for (the) ecstasy of doing something unprecedented," he said, of shaming administrators who claim their networks are bulletproof.

Their actions don't always mesh with that claim, however.

Desh said he is motivated by objections to "1. the abuse of power. 2. the lack of transparency."

Some of their hacks are clearly political. They defaced the website of the Peru-based Antamina copper mine in 2012 after the multinational consortium's slurry pipeline burst, sickening dozens. Rat's idea, said Desh.

And they defaced the Venezuelan ruling party's website again in February in support of anti-government protesters, entering through one of the backdoors they say they secretly leave in networks they penetrate.

Desh said they also retain access to the Chilean Air Force network, from which they removed and dumped online last month sensitive documents on arms purchases. They called it payback for Chile's spying on Peru's air force in a case uncovered in 2009.

The hackers, who have 30,200 Twitter followers, say they neither enrich themselves nor do damage with their exploits.

But many believe LulzSecPeru did do harm in accessing the network of the company that manages Peru's top-level domain. In October 2012, it dumped online a database of thousands of names, phone numbers, email addresses and passwords of affected sites included banks, security companies, Google — every domain ending with ".pe"

Desh said Rat did so without consulting him. "I almost killed him that day."

A company representative and leading Peruvian Internet activist, Erick Iriarte, said the hack occurred well before the upload and customers were notified in time to change their passwords. Desh confirmed that the break-in occurred six weeks before the upload.

Across Latin America, government-run networks are generally regarded by state workers as insecure and untrustworthy. A surprising number of senior officials use private email services instead.

Peruvian authorities call LulzSecPeru "cyber-pirates" and say they could face up to eight years in prison under Peru's new computer crimes statute.

But they first must be caught, and independent security experts say Peru's cyberpolice are badly outmatched. LulzSecPeru's first claim to fame was penetrating the Peruvian cyberpolice network in early 2012. It claims it still has hidden backdoor access.

The unit's commander, Col. Carlos Salvatierra, called such criticism unfounded. He would not discuss details of the LulzSecPeru investigation but said it includes "permanent coordination" with other affected governments and has been ongoing for months.

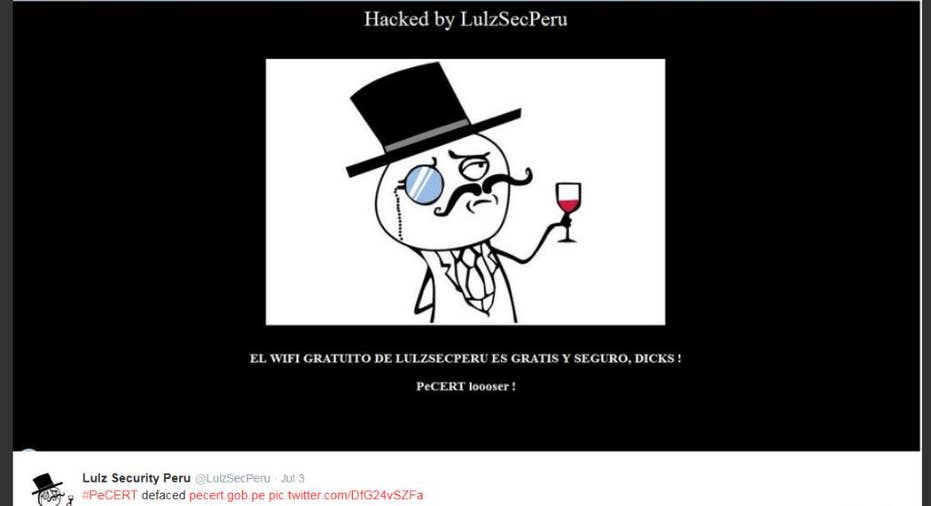

LulzSec as a moniker fuses 'lulz' — which derives from LOL (laughing out loud) and evokes in part the mischievous bliss of hackers who expose sloppy security ('sec'). And there is little greater 'lulz' for the pair than mocking Roberto Puyo, technology chief for Peru's Council of Ministers and the president of the Lima chapter of the Information Systems Security Association, the country's top cybersecurity group.

Puyo did not respond to attempts to reach him by phone and email seeking an explanation for how his network was violated.

Desh said getting inside took him a month.

He said he then routed a carbon copy of all traffic for nearly a month to an external server, capturing Cornejo's email password in the process. Desh said Cornejo's Gmail account was linked to the ex-premier's official email account and that he accessed a mirror of it on the network.

Rat said the hackers are staying away from the Council of Ministers' network for now. He says it now has "honey pots" — traps set to try to ensnare them.

The two say they are confident they cover their tracks sufficiently. And they said they don't tempt fate, keeping U.S. government networks off their target list because they don't want the FBI pursuing them.

"I don't worry that much, though I don't rule out the option that they will trap me," said Desh.

"Nobody is invincible."

_____

Frank Bajak on Twitter: http://www.twitter.com/fbajak