Social Media IPO Bubble Burst Early

Something happened on the way to the next big financial bubble: investors wised up.

Social media stocks were supposed to be the next big thing. In recent years we were told ad nauseum that these companies represent a new paradigm for human interaction, creating vast new communities of like-minded people, raising consumer awareness and facilitating business-to-business commerce.

Everyone's on Facebook (NASDAQ:FB), right?

Absolutely, and the $500,000 home you paid too much for in 2005 should be worth $1 million by 2010. And all those dotcom companies from the late 1990s were worth every penny of their multi-million dollar stock valuations even though most of them weren’t real companies.

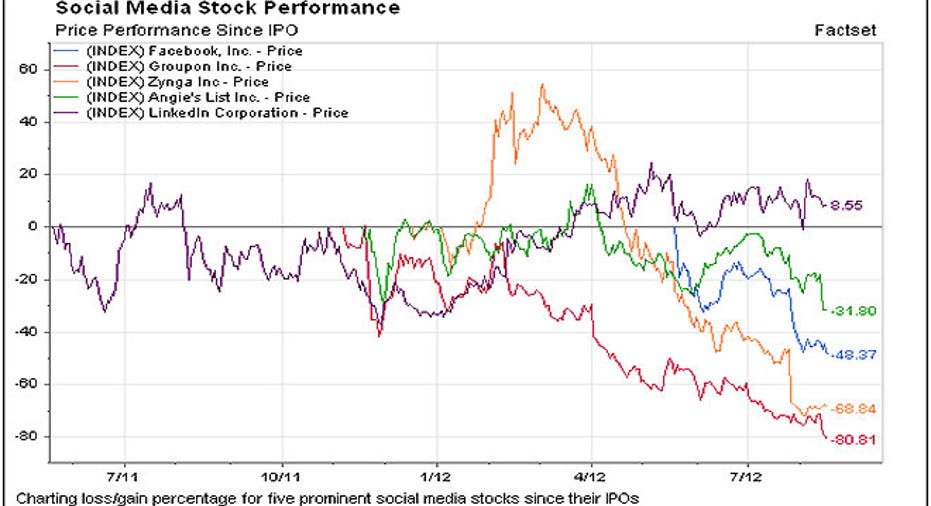

Make no mistake, Facebook, Zynga (NASDAQ:ZNGA), Angie’s List (NASDAQ:ANGI), Groupon (NASDAQ:GRPN) and LinkedIn (NASDAQ:LNKD) are all real companies with employees, corporate headquarters and boards of directors. Some of them even turn a profit. But only LinkedIn, a sort of Facebook for professional networking, has performed well as a publicly traded stock.

The others, despite lots of media hype and buildup from Silicon Valley and Wall Street, have stumbled badly following their initial public offerings. Perhaps none more than Facebook, the supposed archetype of all things social media.

What happened?

"Nowadays they need to perform like GM and Cisco, like real companies."

Times have changed since the dotcom boom and bust era of the late 1990s, when “you could have bought a desk and chair public and it would have gone up, it was that ridiculous,” said Scott Sweet, an analyst at IPO advisory firm IPO Boutique.

The new batch of Internet darlings need to perform, Sweet said, and so far their “numbers aren’t satisfactory…Nowadays they need to perform like GM (NYSE:GM) and Cisco (NASDAQ:CSCO), like real companies. The only one that has done that is LinkedIn and that’s the only one that’s performing.”

In stark contrast to the late 1990s, investors are ignoring the hype and are instead playing it smart and safe rather than chasing quick profits and getting badly burned over the long-haul.

Facebook Has Yet to Justify a $100 Billion Valuation

With nearly a billion users worldwide, Facebook has emerged in the space of less than 10 years as a social and corporate phenomenon. But even as the company edged closer to its long-awaited IPO -- the most-high profile stock debut since Google (NASDAQ:GOOG) in 2004 -- there was a healthy debate underway between the Facebook true-believers and its skeptics.

The true-believers wondered how could a company with nearly 1 billion customers and climbing not make money off those customers. The skeptics said fine, but show us how Facebook can justify its $100 billion IPO valuation. Facebook hasn’t done that yet.

Big advertisers are apparently still reluctant to shell out large sums of money to advertise on the site, unconvinced that Facebook is a catalyst for commerce. GM articulated this concern just ahead of Facebook’s IPO, pulling its advertising on the site in a move that may have foreshadowed Facebook’s disastrous debut as a publicly traded stock on May 18. Facebook’s stock is off about 45% from its IPO price of $38 and dropped another 6%, to a new intraday low, on Thursday as its first lockup period expired.

Facebook doubters have also questioned whether the company has a plan to generate ad revenue from its millions of users who only access the Internet via their smartphones.

Online deal company Groupon, which isn’t really a social media site but got thrown into the sector nevertheless, might have served as a cautionary tale for Facebook. But it didn’t.

Despite genuine concerns for the long-term viability of its business model, raised loudly by analysts ahead of Groupon’s November IPO, the Chicago-based company priced its shares at $20 and investors were initially rewarded: the stock rose above $30 on its first day of trading. At $30 per share, Groupon was valued at $19.5 billion.

The social media bubble seemed to be gaining air.

But within weeks Groupon’s stock had fallen below the IPO price and it’s now trading at around $5.40 amid news earlier this week that growth of its deals business is slowing and that a plan to sell items directly might be more expensive than earlier predicted.

Prior to the IPO analysts had warned that Groupon was already facing stiff competition from competitors and that the coupon business itself is extremely cash-intensive. Groupon has since been criticized (and its stock pummeled) for using accounting methods that tried to hide its extensive expenses.

Meanwhile, Zynga, maker of the popular FarmVille game played mostly on Facebook, priced its IPO shares at $10 in December, raising over $1 billion through the deal and briefly valuing the company at about $9 billion. The shares were trading at $3 this week as analysts have openly questioned whether social gaming is nothing more than a fad. Angie’s List, which allows consumers to write and read reviews of local businesses, has fared a little better, only falling below its $13 IPO price recently.

The Bubble Burst on May 18 (Facebook’s IPO)

Sam Hamadeh, chief executive of data research firm PrivCo., said signs of a bubble were emerging all across the social media sector in late 2011 and into 2012 even as many questioned the lofty valuations awarded companies with little or no revenues.

For instance, on May 17, the day before Facebook’s shares debuted, social networking site Pinterest raised $100 million in funding, a deal that valued the company at $1.5 billion. And a month earlier Facebook paid a staggering $1 billion for picture-sharing app Instagram.

“The bubble did happen to an extent,” said Hamadeh. “At least until May 18 (Facebook's IPO date), that was the day the world changed for social media valuations.”

Hamadeh said the tech boom and bust of a decade ago has thankfully cast a long shadow, providing some much-needed skepticism among investors. For a bubble to fully inflate, a lot of people -- company executives, Wall Street bankers, Silicon Valley venture capitalists -- have to “willfully look the other way,” Hamadeh explained. “It’s in their financial interest to look the other way and cheer on another bubble.”

In the case of social media stocks at least, investors have refused to be swayed by those who would look the other way.