Russian meddling: 5 things tech giants need to tell Congress

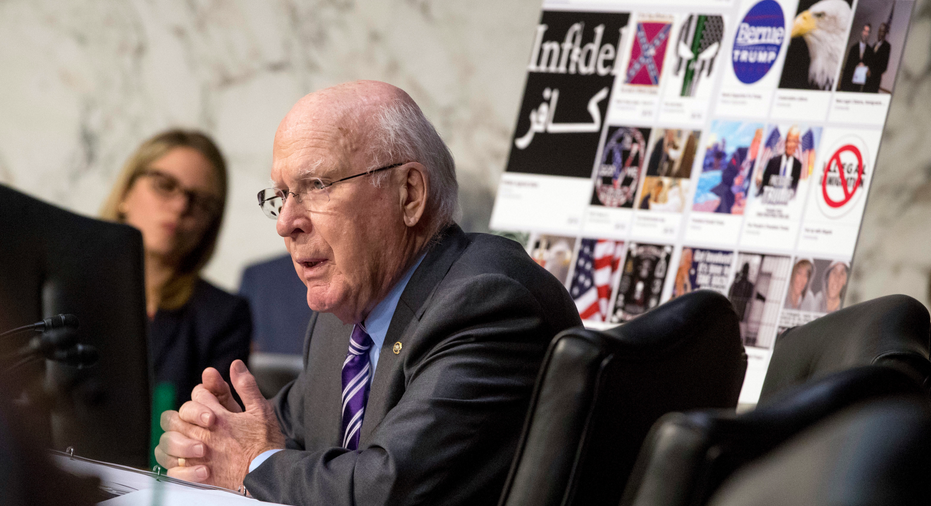

NEW YORK – Facebook, Twitter and Google acknowledged to U.S. lawmakers on Tuesday that Russian-linked accounts began exploiting their services in 2015 to sway last year's presidential election. Lawyers for the companies were grilled about why they didn't notice how their platforms were misused earlier, and about what they have done — and will do — to prevent such abuse from happening again.

Here are five things the companies need to tell Congress:

WHY SO LATE?

The election was nearly a year ago. Why did it take so long for Facebook, Google and Twitter to see how their platforms were used by foreign actors to influence the election?

Congress would really like to know. As Sen. Al Franken, D-Minn., put it: "People are buying ads on your platform with rubles. They are political ads. You put billions of data points together all the time, that's what I hear that these platforms do. They are the most sophisticated things invented by man, ever. Google has all knowledge that man has ever developed. You can't put together rubles with a political ad and go like, 'Hmmm, those data points spell out something pretty bad.'"

In hindsight, Facebook general counsel Colin Stretch acknowledged, the company should have had a "broader lens." He also noted that the company published research in April disclosing that governments and other malicious non-state actors were using its social network to influence elections — though the company didn't directly name Russia at the time.

WAS IT JUST RUSSIA?

It's already illegal for Russians and other foreigners to pay for U.S. political ads. But some lawmakers suggested there was no way for tech companies to know if entities from other countries — like China, North Korea, or, in one memorable exchange, Turkmenistan — had also misused their platforms. After all, they didn't know about Russia's efforts for a long time, either.

With 5 million advertisers every month, Louisiana Sen. John Kennedy asked of Facebook, "How can you be aware?" Especially, he said, when companies and others can hide behind shell companies to mask their true identities.

Stretch stopped short of saying with certainty that other countries didn't purchase misleading or false ads on Facebook.

PUBLISHERS OR PLATFORMS?

Kennedy also asked Richard Salgado, Google's director of law enforcement and information security, whether the company is a "newspaper" or a neutral tech platform. Salgado replied that Google is a tech company, to which Kennedy quipped, "that's what I thought you'd say."

The other two companies also consider themselves technology platforms that merely allow newspapers and other media companies to share information. But at a time when millions of Americans count Facebook, Twitter and Google their primary news sources, the companies will likely have to try harder to convince lawmakers and the public that they are not in the media business.

The distinction is important when it comes to regulation. Tech platforms are generally not responsible for the content on their sites. Media companies are.

IS THERE MORE?

Facebook has already disclosed that content generated by a Russian internet agency potentially reached as many as 126 million users. Twitter told the same subcommittee that it has uncovered and shut down 2,752 accounts linked to Russia's Internet Research Agency, which is known for promoting pro-Russian government positions.

And Google said it found evidence of "limited" misuse of its services by the Russian group, as well as some YouTube channels that were likely backed by Russian agents.

But was this all? The companies are not done with their investigations into Russian interference — and Congress may just be getting warmed up.

CAN THEY FIX THE PROBLEMS WITHOUT REGULATION?

Minnesota Sen. Amy Klobuchar pressed representatives of Facebook, Google and Twitter to declare whether they will support the "Honest Ads" bill she has introduced with Sen. Mark Warner, which would bring political ad rules from TV, radio and print to the internet. Each of the tech giants offered only qualified support rather than a straight "yes."

Klobuchar noted that none of the companies included "issue ads" in their updated advertising policies — even though that's what the majority of the Russia-linked ads were. Rather than outright supporting a political candidate, these ads deal with hot-button issues like race and immigration and are designed to sow discord among the public.

"Obviously it would be easier if everyone had the same rules," she said.

__

Associated Press writers Michael Liedtke and Ryan Nakashima in San Francisco and Tom LoBianco in Washington contributed to this story.