Designers Imagine Storm-Proof Coastlines

Superstorm Sandy was the second-costliest natural disaster in U.S. history at $70 billion. And now there are 10 teams working to make sure that kind of economic and physical devastation never happens again.

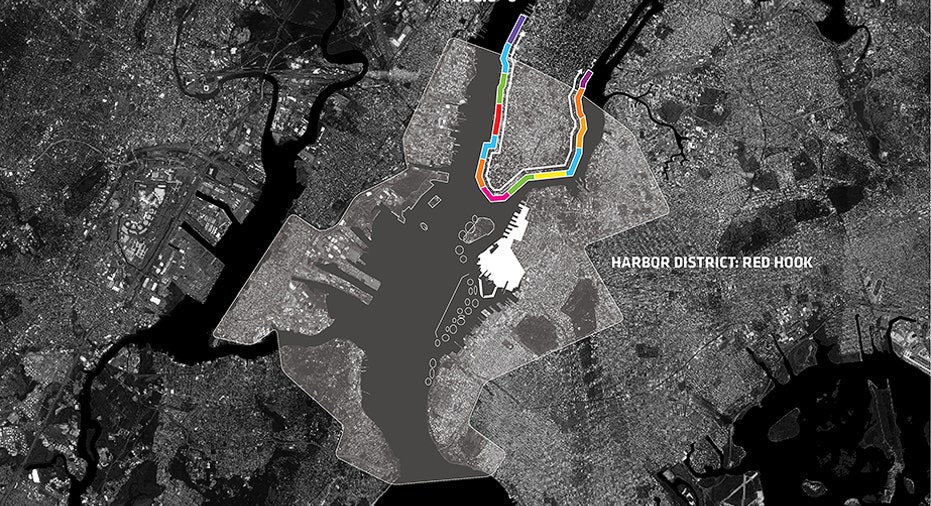

As part of the Hurricane Sandy rebuilding task force called Rebuild by Design, designers this week unveiled innovative plans that could help change the New Jersey and New York coasts forever.

Some designs would drastically alter the appearance of the coast, while others would be implemented into the natural environment, virtually unseen.

All designs would provide some defense against the roaring sea as she barrels toward on-land infrastructure during future epic storms.

“We need to think differently this time around, making sure the region is resilient enough to rebound from future storms,” said Rebuild by Design on its website.

The designers were challenged to find a solution that would address the structural and environmental vulnerabilities that Hurricane Sandy exposed on communities throughout the low-lying regions of the Jersey Shore and New York Harbor.

The teams submitted those initial ideas earlier this week and will now work on refining them into design solutions that can be implemented and funded.

By mid-2014, an expert jury will pick winning solutions to be potentially funded through disaster recovery grants from the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) and other private and public funding.

Those chosen will be a part of the greatest push to innovate shore protection in the Northeast since the region's beaches were naturally formed millions of years ago.

Out-of-the-Box Ideas

Having transformed permeable surfaces into impermeable concrete jungles, modern cities have become virtually ineffective at capturing, storing and even slowing water during floods. Manhattan’s Financial District was a clear case study of this, with tunnels, basements and car garages acting as virtual sewers.

One team, led by the architectural giant Bjarke Ingels Group, proposed a system of levees, berms and barriers that would double as public parks and be hidden in the natural environment. To protect lower Manhattan and Brooklyn, it proposes elevated land, attractive waterfront landscapes and other water-based resilience measures that would protect while simultaneously beautifying the land.

Another team led by Scape/Landscape Architecture believes large-scale artificial reefs would do the trick by helping to break down waves before they reach land.

“Our layered strategy introduces protective breakwaters and interior tidal flats that can dissipate wave energy and slow the water, while rebuilding sustainable oyster population within the Harbor,” the group writes in its proposal.

Another group, known as the Unabridged Coastal Collective, is looking much farther into the future, unveiling a slew of ideas that would change the face of coastal landscapes as water levels continue to rise and storms eat away at beaches.

Predicting that much of Long Island's Rockville barrier island will be under water by 2080, it envisions residents and visitors traveling there via water taxis or elevated public transportation. Once there, they'll fine a community of stilted buildings.

The PennDesign team proposes tall buildings be built in densely-populated urban areas in such a way that they act as levees to low-lying regions.

It also envisions inflatable tunnels and floodable retrofits, and is calling for reshaped and armored creek beds along the five-mile coast of Staten Island’s East Shore. On New Jersey's barrier islands, it is proposing floodable and mobile freight homes.

The Long Battle

The Sandy task force is far from the first attempt to tackle rising seas. The effort has proven not just a difficult one but an expensive one, too –yet pressures are nevertheless building as melting ice caps continue to increase water levels globally.

Millions of dollars have already been spent in the Northeast over the last decade on dredging beaches, which essentially involves a giant vacuum sucking sand from the seabed and depositing it on beaches in an effort to extend them.

Dune replenishment projects have also proven effective, however they tend to be temporary. In a recent analysis of a so-called 100-year storm event, Stockton College’s Coastal Research Center said long stretches of New Jersey's dune system would be “catastrophically inundated" in their current state. A 100-year storm is one that is predicted to strike only once in every 100 years.

Perhaps U.S. designers and scientists can learn from overseas attempts -- many that have been brewing for decades -- to protect their own terrain.

In Venice, construction began a decade ago on a system of 78 giant metal flap gates that would normally rest flat on the seabed but be blasted with compressed air so as to block rushing waters when they get to dangerous levels.

The $7.3 billion project, known officially as the Experimental Electromechanical Module, or “Moses” for short due to its ability to part the sea, was tested for the first time in earlier this month.

However Moses, which would ultimately be implemented on more than a mile of seabed, intended to block at least three inlets, has hit major roadblocks. The project, was initially expected to go into production in 2014, has been pushed back to at least 2016.

The Dutch, meanwhile, have spent considerably more than $7 billion and 50 years on their project dubbed Delta Works that is comprised of barriers and dams designed to protect populated areas near river mouths. However, the project is expected to take several more years, and cost billions of more dollars, for completion.

Perhaps one of the most effective solutions has been London's 520-meter Thames Barrier. Located downriver, it is one of the world’s largest movable flood barriers, acting as a mobile levee that protects 125 square kilometers (78 miles) of London from dangerous storm surges.

The Thames also has hundreds of other industrial and minor floodgates to protect the at-risk residential properties along its banks.

However, even that success story has its issues. As tides continue to rise at unprecedented levels, there is fear that the U.K.’s busiest city could be at risk if the barrier, put into operation in 1982, is not soon upgraded.