Everything You Need to Know About Megabank Earnings in 7 Charts

Last week, all four of the so-called "megabanks" in the U.S. reported their results for the 2016 first quarter. The quarter was a true mixed bag for these behemoths, leaving many investors scratching their heads and trying to figure out what's next.

Now that the numbers are tallied, let's break down exactly what happened to understand how to proceed for the rest of the year.

First, the good newsFirst, all four megabanks beat Wall Street expectations for earnings in the quarter. JPMorgan Chase and Citigroup handily outperformed analyst estimates, while Wells Fargo and Bank of America each squeezed out a narrow win.

This alone was enough to send all four stocks higher for the week. JPMorgan, Citigroup, and Bank of America were all up 3.5 to 4 times the S&P 500 over the course of earnings week, while even laggard Wells Fargo more than doubled the index.

Looking a layer deeper, problems come into focusBefore getting too swept away by the earnings beat and market rally, we need to acknowledge the unfortunate reality of these earnings reports. It is not that these banks did exceptionally well this quarter; it's that they did less bad than everyone expected.

There's no better place to see this than in each bank's profits, all of which were down substantially. The following chart shows the quarterly declines compared with the 2015 fourth quarter.

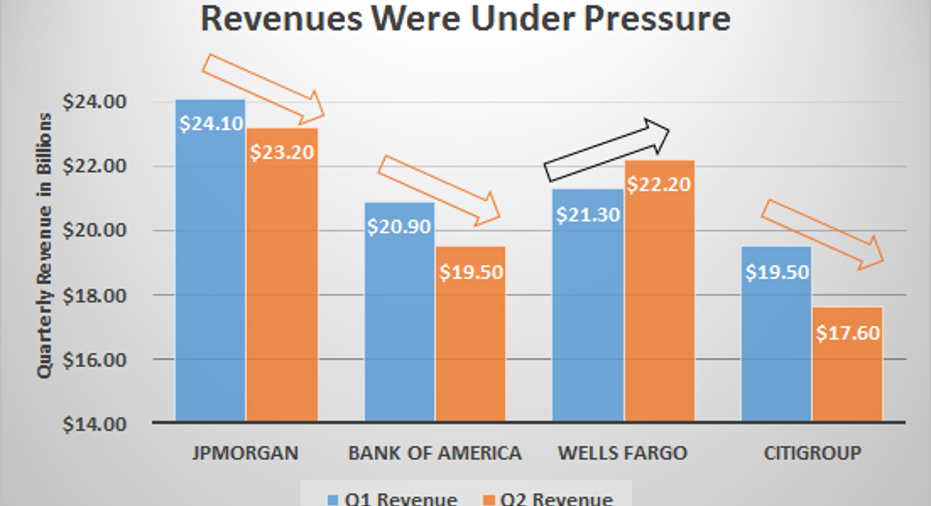

The drop in profits was driven by a number of factors, but in general the problems start with a drop in top-line revenue. Wells Fargo is the lone exception here, and we'll discuss why in just a moment.

Longer term, bank revenues stand to benefit from a rising-interest-rate environment as the Federal Reserve unwinds in near-zero interest rate policy put in place during the financial crisis. The exact timing and magnitude of those increases is anyone's guess, so as a bank investor, I wouldn't hold my breath waiting for this macroeconomic change to jump start revenue. There are more pertinent and immediate problems that need to be addressed first.

What's behind the low expectations and generally poor performance?The largest culprit behind the drop in profits and revenues is from a decline in the trading businesses at these banks, Wells Fargo being the exception. At JPMorgan, 66% of the bank's total revenue decline is attributable to a decrease in trading revenue. The story is the same at Citigroup and Bank of America, with trading contributing 31% and 43% to revenue declines, respectively.

This correlation is to be expected when banks are relying on trading for 20% or more of their total revenue.

The poor trading performance didn't come as a surprise to analysts or bank management. The lower revenue was a direct result of the extreme volatility and market declines seen through the January trading month. The first 10 trading days of 2016 were the worst start to a year ever, and that reality is reflected in the trading numbers at the largest banks.

Among the megabanks, Wells Fargo is the only institution that doesn't rely on trading revenue for a substantial percentage of its top-line performance. At just 0.9% of total revenue, it's barely a blip on the radar screen. That shields the bank from such volatility and is the primary reason that it was the only megabank to grow its revenues quarter over quarter. Wells increased its total revenue by $900 million from the fourth quarter, even while trading revenues declined 50%.

And we can't forget about problems in the energy sectorThe second important issue plaguing the banks this quarter are the troubles from persistently low oil and gas prices. The low commodity prices are driving a mini-crisis in that sector, increasing default rates and loan losses at the banks that serve it.

The megabanks have varying levels of exposures to the energy sector, but all four felt the impact. Banks are required to put aside cash reserves each quarter to guard against future loan losses; those reserves will appear as an expense on the income statement, lowering profitability even before a loan actually creates a loss. In the first quarter, all four megabanks increased the cash they are holding in reserve because of problems in the energy sector.

*Citigroup shown as "reserve build," a unique metric the bank's management uses to measure changing reserve levels. Reserve build is changes in the provision net of charge offs.

In total, Bank of America set aside $997 million in the first quarter. Wells Fargo's increase was the first increase since 2009 and was a large driver of the bank's reduced profitability. JPMorgan's provision increased by 88%. Citigroup's total provision was over $2 billion for the second quarter in a row.

The problems in the energy sector are very real and are having a material impact on the results of these banks. These problems are likely to continue until oil and gas prices rebound to a level high enough to restore profitability to the energy industry.

What's an investor to make of all this?First, don't panic. We've uncovered two primary problems driving the weak first quarter numbers, and I'd argue that neither is of significant long term concern.

Starting with the issues in trading revenue, it's important to remember that the markets have calmed down quite a bit since the January turmoil. The S&P 500 is already back to its pre-January levels after a steady advance beginning in mid-February.

That means more stability in these trading businesses moving forward. Numerous bank management teams have spoken to this in first-quarter conference calls. The second quarter and beyond should produce much better trading results, assuming the market maintains its calm.

With regard to the problems in the energy sector, if commodity prices stay low for an extended period, that could create persistent problems for both the energy sector and the banks doing business in that niche. This wouldn't be good for bank earnings, of course, but I think the problem would be at least a manageable one.

Goldman Sachs recently put out a research report that estimated the total energy exposure in the banking industry to be around 2.5% of total industry assets. For context, the level of sketchy mortgage assets in 2007 was around 33%, more than 10 times higher than energy loans are today. These troubled energy loans are a tough concentration for banks to deal with right now, but it's nothing close to the existential threat the real estate bubble and mortgage crisis was eight years ago. Banks today are well reserved and have higher capital levels and improved liquidity than during the crisis. Taking the long-term perspective, I think the banks will emerge from today's energy environment in very good shape.

Thinking longer term even still, the prospect of a sustained rising-interest-rate environment over the next few years represents a more significant factor in bank stock success or failure. We know that interest rates will rise, but when and how much remains an unknown. As the Federal Reserve manages that process over time, I expect to see increasing bank revenues and profits that will dampen any future trading volatility, counterbalance losses from energy loans, and position banks for long term success.

The first quarter wasn't the prettiest three-month period for these megabank stocks, but stepping back and looking at the longer term, I think these banks are going to end up doing just fine.

The article Everything You Need to Know About Megabank Earnings in 7 Charts originally appeared on Fool.com.

Jay Jenkins has no position in any stocks mentioned. The Motley Fool owns shares of and recommends Wells Fargo. The Motley Fool has the following options: short May 2016 $52 puts on Wells Fargo. The Motley Fool recommends Bank of America. Try any of our Foolish newsletter services free for 30 days. We Fools may not all hold the same opinions, but we all believe that considering a diverse range of insights makes us better investors. The Motley Fool has a disclosure policy.

Copyright 1995 - 2016 The Motley Fool, LLC. All rights reserved. The Motley Fool has a disclosure policy.