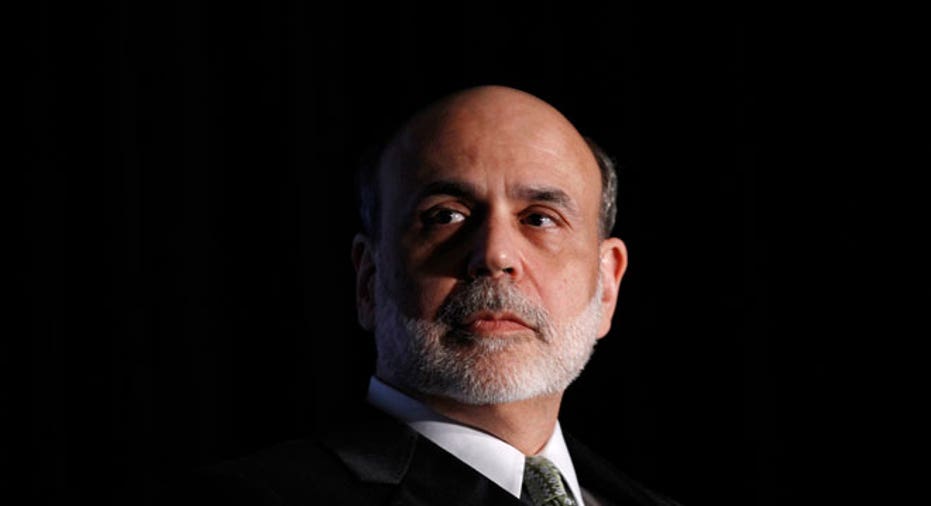

Bernanke Walks Fine Line Between Tranparency and Secrecy

In his own way, even as he has been an outspoken cheerleader for greater transparency, Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke has proven as capable as his predecessor Alan Greenspan at maintaining the veil of secrecy around future Fed policy moves.

That balancing act is expected to continue on Friday when Bernanke gives his yearly speech in Jackson Hole, Wyo., at the Kansas City Federal Reserve’s annual retreat for central bankers.

The tone of his remarks will surely lean toward cagey and cautious rather than casual and off-the-cuff.

If history is any indicator, with regard to any future moves by the Fed, Bernanke is likely to say, “The Fed stands ready to take action when economic circumstances warrant” etc… Or words to that effect. At the same time, Bernanke is expected to offer a thorough if dour assessment of the U.S. economy, which has been stuck in a holding pattern for months with unemployment above 8% and the housing market mired in a deep slump.

No one should be surprised by Bernanke’s cautious approach toward tipping the Fed’s hand. That’s been his tack since succeeding the notoriously elliptical Greenspan at the top of the central bank in 2006.

Bernanke is “very adept” at walking the fine line between transparency and secrecy.

Yet markets have been thin and rudderless all week in anticipation of Bernanke’s comments, as they often are ahead of a major speech by the Fed chairman. As if Bernanke’s going to ease everyone’s mind on Friday by announcing in sharp detail the specifics of a new round of stimulus.

Doubtful.

“One thing that seems likely is that we will not get any grand promise of further accommodation, which, given the way people tend to mis-remember prior speeches, may be enough to disappoint,” wrote Credit Suisse analysts Carl Lantz and William Marshall in a note earlier this week.

It’s often suggested that Bernanke, in his lone break from his usual prudence, gave markets a heads up during his 2010 Jackson Hole speech, hinting broadly that the Fed was planning more stimulus. A second round of quantitative easing, QE2, was announced two months later.

Of course there’s disagreement on Bernanke’s intentions during that earlier speech, a debate the Fed chairman has never bothered to clear up.

In any case, the markets are clearly yearning for a big announcement from Bernanke on Friday. Despite mixed – at best – economic data in recent months, stocks have risen over the summer primarily because investors believe the Fed is ready to act again in a big way, namely through another round of quantitative easing or QE III.

Since the near-financial collapse in 2008, the Fed has purchased more than a trillion dollars in U.S. securities in an effort to boost prices, lower interest rates and pump liquidity into the sluggish economy. While most economists believe the unorthodox moves helped pull the U.S. back from the financial abyss, there is a healthy debate whether another round can actually spur economic growth.

That debate is especially strong among some regional Federal Reserve Board members, several of whom have publicly said the Fed should refrain from any more stimulus programs because of the risk of higher inflation.

Investors, who view loose monetary policy as a positive because it drives up demand for goods and thus stock prices, will likely be disappointed Friday and their disappointment will almost certainly lead to a short-term selloff in stocks.

But a lack of commitment from Bernanke on Friday doesn’t mean the Fed won’t eventually enact another round of bond buying. It just means Bernanke is wary of announcing the move too far ahead of its implementation.

Bernanke is “very adept” at walking the fine line between transparency and secrecy, said Bill O’Grady, chief market strategist at Confluence Investment Management in St. Louis.

Bernanke has been at the forefront of an effort to demystify the Fed’s once-secretive methods for setting policy. To wit, his press conferences following some monthly meetings of the FOMC, which sets most Fed policy, an unprecedented move for a U.S. Fed chief.

Bernanke is also behind the Fed’s move adopted earlier this year to start publishing its forecasts for interest rates in an effort to give businesses a heads up as to what Fed policy makers might be doing down the road.

But Bernanke is well aware of the pros and cons to transparency.

According to the more-transparency-is-better school, letting markets know what the Fed is doing, when they’re going to do it and why reduces the likelihood of unintended consequences resulting from a shift in Fed policy.

For instance, a policy designed to temporarily increase the money supply could be misinterpreted as one intended to have a long-term impact, and the consequences could be dire for consumers and investors who misunderstood the Fed’s intentions.

“The risk you run by being cute (secretive) is that you can get a policy response that you didn’t want,” said O’Grady.

Conversely, there is a long-held school of thought that transparency makes it more difficult for Fed policy to achieve maximum impact.

Under this manner of thinking, “the way to goose the economy through monetary policy is to surprise the market,” said O’Grady. “If that’s what you’re working under then central banks should say nothing.”

Similar to his fiscal policies that also seek a balance, Bernanke is trying to achieve the right balance between silence and transparency.