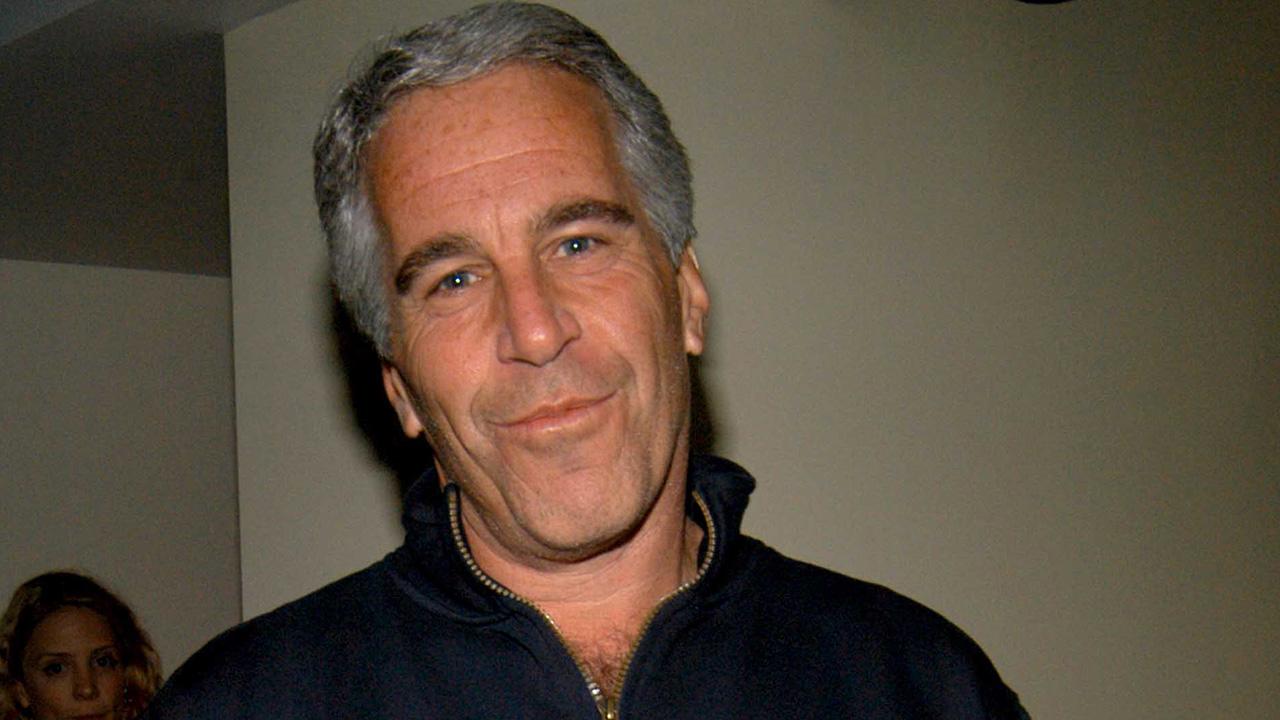

Jeffrey Epstein before he died: “The only thing worse than being called a pedophile is being called a hedge fund manager:” FOX BUSINESS EXCLUSIVE

One of the many tragedies in the Jeffrey Epstein saga is that we will never get to hear Epstein publicly explain himself. His alleged victims will never get their day in court and we will never know how he made his millions to further what the federal government says was a criminal sex trafficking ring, or possibly, how he could live with himself knowing the totality of his life had brought him to a dank jail cell awaiting a trial he was likely to lose.

I can’t offer the true closure that any of his alleged victims need because as we all know, Epstein is dead, having hanged himself in his jail cell last Saturday. But in a small way, I can provide some insight into what was bouncing around inside his head as the judicial vise began to close on him earlier this year.

That’s because I was one of the few reporters to have spoken with Epstein in recent months, just before he returned to the U.S. on July 6 to be arrested on new federal charges of operating a multi-state sex trafficking ring involving underage girls.

I have never met Epstein in person, though I knew of him well. He was a money manager to the ultra-wealthy – he had homes around the world, private jets and friends in very high places (policymakers, major academics, former president Bill Clinton and the current president, Donald Trump, among them), or so I was told by his associates on Wall Street.

I had sources who were close to him while he was at Bear Stearns decades ago and later when he managed private money. His clients included billionaire retailer Leslie Wexner, who runs L Brands, the parent of Victoria’s Secret, and a few select others who were said to have allowed him to trade their wealth through the firm and several other big banks.

They described Epstein as super-rich with mansions in Manhattan, Palm Beach and one on an island he owns in the Caribbean. Rich people hired him because he was great at understanding the tax code for his clients. He was also fun to be around (Epstein was known to date models and society women).

And that's where it ended.

Like most of the world, I would find out that Epstein also had a dark side, having been accused of engaging in sex with underage girls at his Palm Beach mansion between roughly 2005 and 2007.

After taking a plea deal for one count of procuring a minor for prostitution and one count of soliciting prostitution, he spent some time in jail, though apparently not enough. Since his release from prison in 2009, he’s faced victim lawsuits and intense media scrutiny over what was seen as a light sentence crafted by his dream team of lawyers that included Kenneth Starr, Alan Dershowitz and Roy Black, as well as spineless prosecutors.

Despite reading about his case over the years, I never felt a real need to cover Epstein’s sordid legal contretemps primarily because I didn't know what I could add to the story. That changed earlier in the year when several news reports, primarily in the Miami Herald, brought a new perspective to the Epstein imbroglio including a possible motive for his lenient sentencing – that it was the result of Epstein being a cooperator for the government investigating on post-financial crisis-related crimes, including the prosecution of two Bear Stearns executives who ran an ill-fated hedge fund that sparked the meltdown.

I found it an odd rationale for letting someone escape serious jail time for child-sex trafficking mainly because if he was a cooperator, he was a weak one. I covered the financial crisis and its aftermath closely. The feds didn’t charge a single major Wall Street executive with a crime related to the crisis. There were few civil charges against big firms but that's about it. The hedge fund managers were acquitted at trial. Epstein's name never appeared on any witness list.

I put in calls to the usual suspects: Epstein’s lawyers, the prosecutors and the lawyers for the hedge fund managers. They all confirmed my suspicion: Epstein was an investor in the Bear Stearns funds and lost a lot of money when they blew up (around $50 million). He knew a lot of people on Wall Street, but he didn’t help the feds on this case or any other involving the financial crisis.

My next call was to Epstein himself, a long shot to be sure, since he was known as someone who didn't like speaking to reporters. Over the years, he rarely engaged with the press and only when he felt assured he could control the narrative. Those days had long passed.

I was able to obtain his private telephone number through a source who is a major player in New York real estate, so I left a message with a woman who answered the telephone at his Manhattan townhouse, asking that he contact me regarding my story. She said she would relay the message.

A few minutes later, I received a call from a scrambled telephone number. When I answered, a man with a thick Brooklyn accent responded: “Charlie, it's Jeffrey Epstein returning your call.”

It would be the start of several brief but revealing conversations with Epstein, who immediately asked if we could speak off the record. I said I needed to use whatever he said to enhance my narrative and make the piece as fair as possible, and he agreed to speak without the quotes attributed directly to him.

I am now reporting what he said in his own words for a couple of reasons: First, Epstein is dead, and journalists have been known to provide the identities of anonymous sources on important stories once the person has passed (think Woodward and Bernstein’s deal with the Watergate source they called “Deep Throat,” former FBI agent Mark Felt).

More importantly, this qualifies as an important story. Anything we can glean about Epstein, in his own words and not filtered through the nuances of background sourcing, may provide a better understanding of the man and the allegations against him.

I should point out that Epstein, based on our conversations, didn’t seem like he believed he committed much of a crime. He was at times dismissive, and at others, he displayed gallows humor at his predicament, which was growing more acute by the day. It was around this time, in March, that just about every major bank had stopped doing business with him amid the frenzy of press activity. Friends abandoned him or minimized their relationship.

Whether Epstein knew it or not, the feds had opened another investigation that would lead to his arrest months later. My guess, based on the tenor of the conversation, was that Epstein was unaware of the totality of the trouble he faced, or he didn’t care, thinking he would beat the rap again by hiring more high-powered lawyers.

Maybe that’s why before he was arrested, he returned to the U.S. from France, a country with such weak extradition laws that director Roman Polanski, who plead guilty to sexual intercourse with a 13-year-old in the late 1970s, remains there to this day.

I began by asking Epstein about the notion that he served as a government witness for its investigation Wall Street after the crisis. His denial was even more emphatic than his lawyers’. “It’s all b-------,” he snapped.

I referenced an FBI memo dated September 2008 that stated, “Epstein has also provided information to the FBI as agreed upon.” But Epstein said that referenced his cooperation in providing the feds with information about his own case, and nothing more.

I asked him how such a rumor could get started. He pinned it on the same people who were the source of the continued press attention following his 2009 release from prison: Plaintiff lawyers spreading lies and looking to cash in on his wealth by representing women who he said falsely claimed to be victims.

When I asked him to describe the sex acts that landed him in jail, albeit briefly, beginning in 2008 through 2009, he seemed to minimize what had occurred as nothing more than “erotic massages.”

“So you didn’t really know the girls were underage?” I asked at one point. He agreed, stating that what happened to him “wasn’t that much different than what happened to Bob Kraft,” the owner of the New England Patriots, who just a couple of months earlier was charged with soliciting prostitution at a day spa in a Florida strip mall.

“Only he went somewhere, and they came to me,” Epstein explained.

The other key difference, of course, is age: Epstein’s alleged victims were underage, as young as 14, according to the most recent indictment, while Kraft was charged with soliciting prostitution from an adult (Kraft, according to a spokesman, was never arrested and his lawyers are working to get the case dismissed).

Either way, Epstein wanted me to know that despite what I have been reading, he was not the pervert the media is making him out to be.

“I just want you to know I’m not a pedophile,” he said, adding, “Maybe the only thing worse than being called a pedophile is being called a hedge fund manager,” he said with a slight laugh.

Epstein always considered himself a money manager to billionaires, not someone who would hawk a retail product like a hedge fund to mere millionaires.

These were odd conversations; when I called, he would call me back almost immediately, but he was eager to end the conversation quickly. I couldn’t tell if this was just his frenetic nature or he was limiting how much information he wanted to provide.

At one point during our talks, he blurted out the reason he was calling me back: Unlike presumably other reporters, people he knew and liked in the leadership of Bear Stearns respected my work as a journalist.

I must say, Epstein came across as pretty disarming as we chatted about mutual acquaintances from back in Bear’s heyday, though he must also have forgotten (or was unaware) that many Bear executives blamed my reporting back in 2007 and 2008 for the firm’s eventual demise at the start of the financial crisis.

I remember telling him that I was glad he called me back and that I was just looking to do a fair job on an important story. I had no particular ill-will toward him and that people I knew said they knew him to be a decent guy.

“Yeah, Charlie,” I remember him responding, “It’s hard to believe that not so long ago people actually thought I was a good guy. And now people are ashamed to say they knew me.”

All told, I spoke to Epstein about three times in March of this year. His comments did help infuse this piece I wrote for FOX Business that debunked the notion that he was a Wall Street cooperator, and another article in early August that described his Wall Street connections and his attempts to rebuild some semblance of a business after returning from jail in 2009.

A lot happened to him since then; the press frenzy didn’t abate. The U.S. Attorney’s Office for the Southern District of New York – one of the nation's premier law enforcement agencies – had indeed been investigating Epstein for months, putting together a bigger, more damning federal indictment that accused Epstein and unnamed employees of his in multi-state child sex trafficking ring that could have put the 66-year-old financier in jail for the rest of his life if, of course, he had lived to see his trial.

The Miami Herald's reporting on the Epstein's lenient sentencing reverberated in Washington. It was then-U.S. Attorney for the Southern District of Miami, Alex Acosta, who most recently served as President Trump’s Secretary of Labor, who cut an unusual plea deal a decade ago with Epstein’s high-powered team on state charges of prostitution that put him in jail for a little longer than a year.

Epstein would have to register as a sex offender and pay victim restitution, but the deal was done without consulting the victims’ lawyers who could have objected to its lenient terms (Acosta resigned from the Trump administration last month over his handling of the Epstein case, but he maintains he cut the best deal possible given the evidence that was available, and vetted the agreement with his supervisors in the Justice Department).

Epstein was right about one thing: People who once thought he was a great guy continued to abandon him in droves. His old client and mentor, Wexner, issued a statement first saying the two haven’t done business since the financier’s conviction a decade earlier, and then stating Epstein had stolen money from him.

Epstein’s business relationships had largely disappeared; no major bank would now take his money. Former friends said they barely knew him. Trump had to answer for his prior relationship with the disgraced money man, including a 2002 quote where he stated: “I’ve known Jeff for fifteen years. Terrific guy. He’s a lot of fun to be with. It is even said that he likes beautiful women as much as I do, and many of them are on the younger side.”

After Epstein's arrest, Trump said: "I don't think I've spoken to him for 15 years. I wasn't a fan."

Bill Clinton, likewise, sought to minimize his contact with someone he once described this way: “Jeffrey is both a highly successful financier and a committed philanthropist with a keen sense of global markets and an in-depth knowledge of twenty-first-century science.”

I placed a few more calls to Epstein on the day of his arrest, but the telephone simply rang off the hook. The following day, the feds raided his Manhattan townhouse looking for additional evidence. They found a Saudi passport and, even worse for Epstein, a trove of nude photographs of young girls who prosecutors said appeared to be underage, leading to possibly more charges. Since his arrest, Epstein hadn’t made any public comments aside from his not guilty plea.

He appeared to attempt suicide once, unsuccessfully, after being placed in a Manhattan federal jail.

Even after Epstein's death, his lawyers haven’t said much aside from some initial statements calling the government’s case a do-over of the old charges that they will fight vigorously in court so the full truth can come out.

That, of course, is not going to happen, which is why I think there is something important about hearing Epstein in his own words explain and rationalize his behavior without the cloak of secrecy.

I wish I had more from him because we learn about evil by watching it unravel before our eyes.

FOX Business' Lydia Moynihan contributed to this story